by Jochen Markhorst

- Dignity Part 1: A bloody mess

- Dignity Part II: You can never play too much Bob Wills

- Dignity Part III: One line brings up another

- Dignity Part IV: I contain multitudes

- Diginity Part V: Nowhere to fade

VI The gay scientist

In broad lines, the poet Dylan follows the structure in the last quartet as well: two verses around an archetype (here the sick man and the Englishman), the bridge with a biblical allusion (here to the Valley of Dry Bones from Ezekiel) and a literary, concluding “chorus”.

In broad lines, the poet Dylan follows the structure in the last quartet as well: two verses around an archetype (here the sick man and the Englishman), the bridge with a biblical allusion (here to the Valley of Dry Bones from Ezekiel) and a literary, concluding “chorus”.

In terms of content, however, the first stanza, stanza 13, suggests a break with the previous lyrics;

Sick man lookin’ for the doctor’s cure

Lookin’ at his hands for the lines that were

And into every masterpiece of literature

For dignity

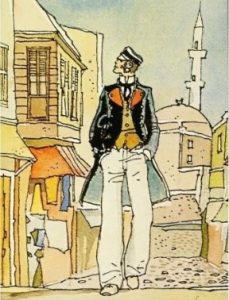

Stylistically still neatly in line. The repeated lookin’ mirrors the duplicated lookin’ from stanzas 1 and 2, the introduction of an archetype (sick man) is consistent with earlier archetypes as blind man, fat man and drinkin’ man and a powerful, mysterious second verse. Lookin’ at his hands for the lines that were is enigmatic, but, remarkably enough, reminds one of the comic, or rather: graphic novel series Corto Maltese by the Italian artist Hugo Pratt (1927-1995). Ugo Eugenio Prat was a great graphic artist who brought literature into the world of comics; his beautiful works are imbued with references to and borrowings from greats such as Rimbaud, Jack London, Melville, Joseph Conrad and more.

That was, in fact, the only correspondence with Dylan’s oeuvre. Up until this one line; Pratt’s protagonist Corto Maltese, a complex character who tries to stay down-to-earth in the midst of magical events and supernatural occurrences, is not entirely insensitive to the mystical: in his early years he recut the “life lines” in the palm of his hand with a knife because they predicted an early death. In one of the albums, a voodoo lady sees right through him, lookin’ at his hands, at the lines that were.

So far not significantly different from previous verses. The raising of the eyebrows is triggered by the third line, the verse line stating that dignity cannot be found in every masterpiece or literature either. This is weird. Either the narrator has a very peculiar definition of “literary masterpiece” or he has been browsing back and forth through those masterpieces very superficially. Homer, Ovid, Kipling, Poe, Goethe, Melville, Kerouac, Blake, Dante, Kafka… it’s actually very difficult to find a writer who does not demonstrate what dignity is, who does not thematise finding or maintaining dignity in one of his stories. In Proust’s À La Recherche Du Temps Perdu the virtue is in the Top 5 of most mentioned qualities, at Chekhov in the Top 3. In Primo Levi’s If This Is A Man it is a red thread. In Auschwitz Levi is hungry for dignity and he knows how to express in which details he, to his relief, still manages to find dignity. “There are few men who know how to go to their deaths with dignity, and often they are not those whom one would expect,” he states in the beginning, and in the continuation he describes vividly, clearly and unambiguously, for the searching storyteller in Dylan’s song, wherein he still manages to see dignity – even in this gruesome, inhumane environment.

So now, towards the end of the song, the listener suddenly has to ask himself: “not to be found in the masterpieces of literature?” It is not to be missed in the masterpieces of literature. Is this really about dignity?

The suspicion that the narrator uses the word “dignity” as a kind of code word, is in fact looking for something other than dignity, tilts – obviously – the whole text. Apparently, the narrator does not mean something like “grandeur, grace, morality”, but some other desirable greatness. A first, and obvious “real” desire of all those archetypes and the I-person would, of course, be Love. Not only because that is the Great, Eternal, Universal Desire (in the end, we are all looking for Love), but also because of that allusion, halfway through Dylan’s lyrics, the allusion to 1 Corinthians 13.

Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians consists of sixteen chapters, and the thirteenth chapter, the shortest chapter (only thirteen verses), is the most popular. Obama quotes from it at his inauguration in 2009, Franklin D. Roosevelt takes the oath with his hand on this chapter in 1933, the Stones use for the title of a Greatest Hits album a Corinthians 13 paraphrase (Through The Past, Darkly, 1969), Joni Mitchell writes a whole song around it (“Love”, 1982), Prime Minister Tony Blair reads from it at Lady Di’s funeral, James Baldwin quotes from it in Giovanni’s Room (1956)… the list of paraphrases and quotes in films, books, songs and speeches could be endless.

Joni’s song, and the Bible chapter open with the words Dylan appropriates:

If I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I am become sounding brass, or a clanging cymbal.

…which immediately sets the tone. The chapter, titled “The Excellence Of Love” in most Bible translations, is a hymn to love, is singing love as Supreme Gift. As in the explicit, unequivocal closing verse 13:

But now abideth faith, hope, love, these three; and the greatest of these is love.

By the way, the most quoted verse does not sing love (verse 11; When I was a child, I spake as a child, I felt as a child, I thought as a child), but the over-all tenor of the short chapter is indeed:

Love is all there is, it makes the world go ’round Love and only love, it can’t be denied No matter what you think about it You just won’t be able to do without it

… as the poet Dylan put it in 1969 (“I Threw It All Away”).

Reading “dignity” instead of “love” in Dylan’s lyrics works, of course, fine. It remains a coherent text, more understandable even, only a little more boring – everybody’s looking for love is not exactly so earth-shattering that it justifies an eloquent 64-line lyric. And true, renaming love to dignity does turn such a hackneyed theme into something much more original and above all: into something much more elegant.

But then again – in that case the stumbling point, verse 51, “every masterpiece of literature”, remains a stumbling point. One cannot claim with a straight face that love is untraceable in these masterpieces, either. If there is one thing that all the greatest poets have been able to express throughout all centuries and cultures…

The same goes for usual suspects such as Happiness, Wisdom, Knowledge or Truth – all quite fitting, until that wretched line 51.

No, then a near-by, semantic association might be more conclusive. Dignity – divinity – deity…. could it be that the protagonist, as well as all those archetypes he encounters along the way, is looking for God?

Possibly. Strangely enough, however, style, theme and choice of words then do lead to the Great Denier of God, to Friedrich Nietzsche – and specifically to one of his greatest works, Die fröhliche Wissenschaft (The Gay Science, or The Joyful Wisdom, 1882):

Haven’t you heard of that madman who in the bright morning lit a lantern and ran around the marketplace crying incessantly, “I’m looking for God! I’m looking for God!” Since many of those who did not believe in God were standing around together just then, he caused great laughter. Has he been lost, then? asked one. Did he lose his way like a child? asked another. Or is he hiding? Is he afraid of us? Has he gone to sea? Emigrated? – Thus they shouted and laughed, one interrupting the other.

From paragraph 125, “The Madman”, which is followed by the famous death announcement.

Die fröhliche Wissenschaft is a treasure chest full of parable-like pieces of prose, hundreds of aphorisms, beautiful poems and some witty paradoxes, such as section 255:

Imitators. – A: “What? You want no imitators?’ B: “I don’t want people to imitate me; I want everyone to set his own example, which is what I do.” A: “So -?”

The work, which he would later call “my most personal work”, is divided into five books, in which Nietzsche deals with such diverse themes as the limitations of science, nihilism, the essence of art and the value of religion.

In the poems and in the parables, we encounter quite a lot of “Dignity”-like archetypes: The wise man (section 49), the poor (185), a sick man (168) and so on. The poet Dylan could have found inspiration for his obfuscation in section 6: “Loss of dignity”. And for the plot in the quatrain “The Sceptic Speaks” (section 61);

Long roaming forth it went and searched but nothing found - and wavers here?

Comfort and fatherly advice the stranded storyteller from Dylan’s “Dignity” can also find at Nietzsche, already on page 1, in section 2, “My Happiness”:

Since I grew weary of the search I taught myself to find instead.

And Dylan himself may identify with what Nietzsche writes about The Gay Science in his autobiography Ecce Homo. After elaborating on the Provençal origins of the concept of gaya scienza, the philosopher recalls the grandeur of the first, medieval troubadours, which we also owe to Provence, “jene Einheit von Sänger, Ritter und Freigeist, that unity of singer, knight and free spirit…” that list could be endless too.

About the author

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

12 years of Untold Dylan

Although no one gets paid for writing, publishing or editing Untold Dylan, it does cost us money to keep the site afloat, safe from hackers, n’er-do-wells etc. We never ask for donations, and we try to survive on the income from our advertisers, so if you enjoy Untold Dylan, and you’ve got an ad blocker, could I beg you to turn it off while here. I’m not asking you to click on ads for the sake of it, but at least allow us to add one more to the number of people who see the full page. Thanks.

As for the writing, Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Although no one gets paid, if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8500 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

Love with dignity is a hard card to play

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/151/Dignity

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.