by Jochen Markhorst

- Tombstone Blues (1965) part I: Daddy’s looking for the fragmentation bomb’s fuse

- Tombstone Blues part II: Duck back down

- Tombstone Blues (1965) III Let’s Go Get Stoned

IV Medicine Man

The hysterical bride in the penny arcade

The hysterical bride in the penny arcade

Screaming she moans, “I’ve just been made”

Then sends out for the doctor who pulls down the shade

Says, “My advice is to not let the boys in”

Now the medicine man comes and he shuffles inside

He walks with a swagger and he says to the bride

“Stop all this weeping, swallow your pride

You will not die, it’s not poison”

Cocaine, heroin, morphine, alcohol … the popularity of many “medicines” in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is partly due to ingredients that have lost much of their beneficial image today.

Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup is “perfectly harmless and innocent” and fully accepted to give to “fussy children” to grant them a “natural quiet sleep, relieving the child from pain”. It is, in fact, a mixture of morphine and alcohol.

Cocaine is in everything from cough syrup to tooth powder, menstrual pains are fought with every conceivable opiate, and even Thomas Jefferson, despite being a critical and educated man, fights his chronic diarrhea with laudanum. With addicting outcome; on his estate in Monticello he grows his own opium poppy. He does like it; “with care and laudanum I may consider myself in what is to be my habitual state,” he writes to a friend (in which of course the word habitual stands out). Recruiting words apparently; later, Lincoln’s wife Mary Todd also develops quite a laudanum addiction.

The “women’s disease” hysteria is no less spectacularly treated, from the Middle Ages until Freud. Initially it is suspected that the uterus is searching for a child, which then causes the hysterical attacks, later it is generally agreed that a lack of sexual contact must be the cause. Until well into the nineteenth century, there was medical consensus on the treatment as well: vaginal massage by a midwife or doctor. Liberating orgasms should cure the patient from her suffering.

Unfortunately, there are no reliable statistics on the success of treatment.

Freud, as he usually does, puts an end to the fun. Although the Viennese doctor’s diagnoses usually target pubic areas, and although he is not at all averse to cocaine, he tries to treat precisely female hysteria with “normal” therapy. Well, with what we call “normal therapy” these days, anyway. His Studien über Hysterie (1895) describes five case studies and is in fact the beginning of classical psychoanalysis.

However, Dylan’s hysterical bride seems to fall into the hands of an old-fashioned therapist. At any rate, her psyche is not being analysed.

The hysterical bride part is the most compact octave of the song, suggesting, more than the other five octaves do, a rounded tableau with the promise of a real narrative and thus seems more like a preliminary study for a “Desolation Row”-couplet.

The archetype hysterical bride is here, by Dylan standards that is, surprisingly true to character. Her whereabouts, the penny arcade, may be alienating, but apart from that she meets the norm: she screams, moans and is weeping. Granted, “screaming she moans” is an unusual word combination, but both verbs do fit hysteria.

Her opponent, the doctor, is introduced with a rather lame but still effective pun; the doctor who pulls down the shade – in other words: a shady type, a dubious subject who wants to escape the daylight. He is further characterised by his walk; swagger and shuffle suggest a philanderer type and an unprofessional, groping continuation. A suggestion reinforced by his choice of words: “Swallow your pride, you will not die, it’s not poison” at least insinuates an (oral) rape scene.

It is not unambiguous. The change of job title (from doctor to medicine man) and the word poison do point to nineteenth-century medicine as well; to opiates, in other words. Not too far-fetched. Dylan has used the word medicine only three times in his entire career. All three times in these five hundred mercury days, and all three times in an ambiguous, drug-inducing context:

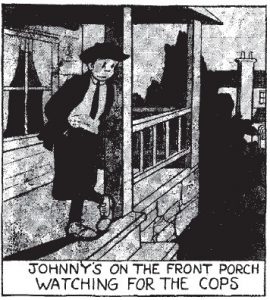

Johnny’s in the basement

Mixing up the medicine

("Subterranean Homesick Blues", January ’65)

Now the rainman gave me two cures

Then he said, “Jump right in”

The one was Texas medicine

The other was just railroad gin

("Stuck Inside Of Mobile With The Memphis Blues Again", February ’66)

In these same days, spring 1965, Dylan sits with Brother Bill, with William Burroughs, in a pub in Greenwich Village. Dylan is a fan and does not hide his admiration. In March ’65, just before the songwriter produces “Tombstone Blues”, he is interviewed by Paul J. Robbins, and he says:

“I’ve written some songs which are kind of far out, a long continuation of verses, stuff like that – but I haven’t really gotten into writing a completely free song. Hey, you dig something like cut-ups? I mean, like William Burroughs?”

The similarities between Burroughs’ work and Dylan’s experimental novel Tarantula are unmistakable anyway, but cut-up also leaves its mark on the songs from this period. Perhaps the songwriter – mentally at least – even did cut and paste from Burroughs’ work; not “completely free”, but still. A word like medicine Brother Bill uses in every book, usually as a euphemism for mind-expanding drugs. As in Junky:

The guard says to me, “Drug addict! Why you sonofabitch, you mean you’re a dope fiend! Well, you’ll get no medicine in here!”

And in Nova Express (1964) we find enough words in a single paragraph to cut and paste a Dylan couplet:

“We hit the local croakers with “the fish poison con” – “I got these poison fish, Doc, in the tank transported back from South America I’m a Ichthyologist and after being stung by the dreaded Candirú – Like fire through the blood is it not? Doctor, and coming on now” – And The Sailor goes into his White Hot Agony Act chasing the doctor around his office like a blowtorch He never missed – But he burned down the croakers – So like Bob and me when we “had a catch” as the old cunts call it and arrested some sulky clerk with his hand deep in the company pocket, we take turns playing the tough cop and the con cop – So I walk in on this Pleasantville croaker and tell him I have contracted this Venusian virus and subject to dissolve myself in poison juices and assimilate the passers-by unless I get my medicine and get it regular.”

Poison, medicine, doctor, and the opponent is called – what’s in a name – “Bob”, on the pages before and after there is striking idiom such as screaming, hysterical and penny arcade to be found… reading Brother Bill’s work has given a great thrill, that much seems obvious.

To be continued. Next up: Tombstone Blues part V

———–

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits (German)

Untold Dylan

As we approach 2000 articles on this site, indexing is important, but sadly chaotic. You can find indexes to series linked under the image of Dylan at the top of the page and some relating to recent series on the home page.

Although no one gets paid for writing, publishing or editing Untold Dylan, it does cost us money to keep the site afloat, safe from hackers, n’er-do-wells etc. We never ask for donations, and we try to survive on the income from our advertisers, so if you enjoy Untold Dylan, and you’ve got an ad blocker, could I beg you to turn it off while here. I’m not asking you to click on ads for the sake of it, but at least allow us to add one more to the number of people who see the full page including the adverts. Thanks.

As for the writing, Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Although no one gets paid, if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8500 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

In Tombstone Blues, the doctor and the medicine man are two different people. The doctor has come and given advice and then “the medicine man comes”. The doctor represent Western medicine. The medicine man represents native American culture.

Their advice is entirely different. One, the doctor, prescribes caution around men. The other, the medicine man, says it’s no big deal.

The penny arcade is used because it rhymes… this song is meant to be funny, not important. So it’s not serious, and for songs that aren’t serious, sometimes you just need a rhyme. But if you’re looking for analysis, those were arcades in the days before video. They had pinball machines, where you pulled back a rod on a spring, and sent a ball rolling around. It’s a rod, a ball, and a hysterically bride complaining that she’s been made, i.e. that someone has sex with her. But I doubt it’s that sophisticated. I think it’s there because it rhymed and just had to be funny.