This article continues from “Arthur Rimbaud: The Discovery of two new portraits of the planetary poet-laureate Part 1”

Part 2: Authenticity and implications

by Aidan Andrew Dun

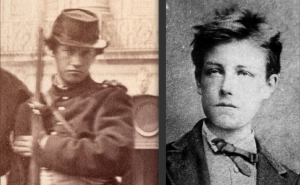

Are these images genuine? To my way of thinking they are authentic. The chin and the mouth are unquestionably Rimbaud’s. Examine closely the slight asymmetry of the Cupid’s bow, one of Rimbaud’s most famous features (apart from his turquoise eyes).

Are these images genuine? To my way of thinking they are authentic. The chin and the mouth are unquestionably Rimbaud’s. Examine closely the slight asymmetry of the Cupid’s bow, one of Rimbaud’s most famous features (apart from his turquoise eyes).

Looking closely you will notice that the central portion of the upper lip is shifted very slightly to the left side of the poet’s face. Now look at the perfect oval of the chin. The harsh and infinitely sad expression of the mouth is offset by this perfectly rounded chin: feminine, cherubic and utterly recognizable.

The real problem in the first image is the nose. It looks too broad and flat. Yet if you look closely you will see a white square of light beginning on the bridge of the nose, ending at the tip. This square of light seems to spread the nose laterally. If you half-close your eyes the square disappears and the nose becomes Rimbaud’s: thin with a slightly upturned tip. I feel that this square of light is almost certainly an optical effect – caused perhaps by enlargement of the image – but a professional opinion is needed here. What is certain is that when the square is filtered out the problem disappears.

Arthur Rimbaud – the rara avis of all time – appears to have been fabulously captured in collodion-brown. Yet scowling out of the new portrait the world’s most controversial poet may be secretly smiling to himself.

Hardcore Marxists are going to jump on these images as proof that Rimbaud was a full-blooded Communard. And as contemporary poster-boy for Extinction Rebellion the teenage Communard Arthur Rimbaud will empty classrooms faster than Greta Thunberg.

But the truth is that Rimbaud was a magpie-Marxist at best. After the dissolution of the Commune he became rapidly depoliticized. Admittedly at the time – aged sixteen – he was one-hundred percent drunk with utopianism. While the red flag flew over the Hotel de Ville Rimbaud saw himself as a partisan. (Of course in the 1870’s this was still the flag of the French – not the Bolshevist – revolution.) In the Place Vendome he incarnates the Commune. But the image’s significance is much greater than this. It is not just Napoleon that Rimbaud topples with a casual nudge from his left elbow. By implication it’s the whole military industrial complex.

Many people are in for a shock. The Rimbaud damage-limitation exercise is over. With the emergence of these new photographs it is time to conclude that Arthur Rimbaud went through a phase of proto-communism when Paris became an experimental city-state the poet was on the frontline of class-war. (Graham Robb, Rimbaud’s best biographer by far, has taken the view that any role in revolutionary Paris was fairly minimal; while Terry Eagleton and Kristin Ross are now likely to see, however wrongly, radical political convictions reinforced.)

Yet, as the dust settles after the controversial materialization of Rimbaud in the Place Vendome, it must be remembered that after the failure of the Commune the poet continued to evolve a supernaturalist philosophy. Without a massive cosmic frame of reference even Rimbaud could never have written A Season in Hell. The confessional metaphysics of this work far transcend dialectical materialism. And Rimbaud’s primary, non-reductionist faith will always be in the occult praxis of his art. At the height of his powers (in ’72 and ’73) he believes that the world can be magically transformed through his art. His engagement is truly with his holy guardian angel.

I repeat: many are going to read into the new images a narrative affirming Marxist engagement. Yet this would be a selective interpretation. In The Emergence of Social Space: Rimbaud and the Paris Commune I note that Kristin Ross makes no mention at all of the Rue d’Babylone assault – when Rimbaud was almost certainly gang-raped in a Commune barracks. This ordeal takes place only a week before the photo-shoot in the Place Vendome.

All the maladjustment to come pours out of the vortex of what the poet goes through at this time. All Rimbaud’s cruelty to his only real love – Paul Verlaine – is explained by events in the Rue d’Babylone. The harsh and sad expression in Rimbaud’s face as he stands in the Place Vendome has to be related to this recent nightmare experience. Yet Kristin Ross does not – in her rush to recruit Arthur Rimbaud for the revolution – even critique Stolen Heart, the poem which dramatically codifies the poet’s core-trauma, the poem in which the poet’s heart is ‘degraded’ by the ithyphallic soldiery.

In my opinion Rimbaud’s text is excluded on purpose since the poem makes manifest a dystopian aspect of the Commune. (Revolution has changed everything except the human heart.) In a sometimes highly perceptive investigation Ross more or less overthrows her own thesis by this glaring omission. And similar errors of selective analysis need to be avoided when deconstructing the new images.

After the rape in the Rue d’Babylone Rimbaud doesn’t give in. The poet is not defeated. He doesn’t go back to his hometown and collapse in provincial bitterness. Instead he issues his doctrine of the Seer – Suffer everything so as to be in mystic solidarity – and returns to Paris to take a heroic stand. His face tells the full horror of what he has been through. But in the Place Vendome he shows what it means to be a hero.

Ecce homo.

Let’s leave the last word to Rimbaud himself. Let’s have the poet tell us precisely what he thinks about armed risings.

At dawn, armed with burning patience, we shall enter the splendid cities.

Here the impatience of the revolutionary, the understandable hunger for change, has been transformed into something far more impressive. Now the enemy within has been identified. Now the ultimate traitor has been exposed. Instead of burning Paris (as the Communards did when outgunned and outmanoeuvred by the Versaillais) Rimbaud lights the lamp of interior alchemy and says with Mahatma Gandhi:

Be the change you wish to see in this world.

Meanwhile elsewhere

There are details of some of our more recent articles listed on our home page. You’ll also find, at the top of the page, and index to some of our series established over the years.

If you have an article or an idea for an article which could be published on Untold Dylan, please do write to Tony@schools.co.uk with the details – or indeed the article itself.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with getting on for 10,000 members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

The problem being that there is no clear evidence that Rimbaud was in Paris around the time of the toppling of Napoleon’s statue, but likely in Charlesville.

Then again there is no clear evidence either that he could not have been in Paris at the time the photograph was taken.

Whether the ‘nose’ have it is uncertain??

*Charleville