by Jochen Markhorst

- Gates Of Eden part I: The Lady In The Water

- Gates Of Eden part II: As if he was just taking dictation

- Gates Of Eden part III: Hello lamppost, nice to see ya

And also… The Multiple Gates of Eden

it’s iron claws The lamppost stands with folded arms / pretends to be ^ attached t the curbs neath wailing babies - tho it’s shadow’s metal badge / All in all, can only fall, with a crashing but meaningless blow No sound comes from the depths of Eden

The deletions and rewrites of the opening line are not too spectacular; the poet evidently feels that the chilly, heartless aura of the lamppost gains undercurrent aggression by replacing “pretends to be attached” with “its iron claws attached”. And so it does, of course. It’s still fourteen syllables, the rhyme word stays and the iambic metre is maintained, so technically it doesn’t matter. Much the same goes for the next line, “t the curbs neath wailing babies”, which four months later, at the time of recording, has been changed to “to curbs ‘neath holes where babies wail”; it seems mainly an action to save the iambic. At the expense of semantics, admittedly (“curbs beneath holes”? or “the lamppost beneath holes”?), but who cares. Deconstruction, and all.

The deletions and rewrites of the opening line are not too spectacular; the poet evidently feels that the chilly, heartless aura of the lamppost gains undercurrent aggression by replacing “pretends to be attached” with “its iron claws attached”. And so it does, of course. It’s still fourteen syllables, the rhyme word stays and the iambic metre is maintained, so technically it doesn’t matter. Much the same goes for the next line, “t the curbs neath wailing babies”, which four months later, at the time of recording, has been changed to “to curbs ‘neath holes where babies wail”; it seems mainly an action to save the iambic. At the expense of semantics, admittedly (“curbs beneath holes”? or “the lamppost beneath holes”?), but who cares. Deconstruction, and all.

All of it less interesting, in any case, than the last words: “from the depths of Eden”.

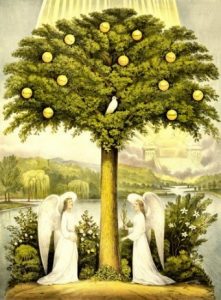

It illustrates that, for the time being, the poet still relies on the course of his stream of consciousness – and that the strong, evocative metaphor gates of Eden has not been the trigger of his poetic flash. In this first draft (we are now two stanzas including two François Villon-like refrain lines into the journey), the word gates has still not bubbled up from the stream. Maybe it’s even a shame that those gates will pop up a little later and displace the depths. “Depths of Eden” is more threatening anyway, but actually also more fascinating than “Gates of Eden”. The gates represent the lost paradise, the price we have paid for disobedience, barring access to the Tree of Life – it is, in any case, a fairly unambiguous image.

“Depths of Eden”, on the other hand, is an unfamiliar, even alienating image. In general, Biblical depths are the opposite of paradise. They depict despair (Out of the depths have I cried unto thee, O Lord, Psalm 130), or something like “far, lonely and lost” (usually depths of the sea and depths of the waters), or the literal opposite of paradisiacal Eden, hell (the depths of hell, Proverbs 9; the depths of Satan, Revelation 2:24). “Depths of Eden” is thus a catachrese, a contradiction almost, inviting associations like the serpent lurking in the depths of Eden, or perhaps the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, its roots reaching deep into the depths of Eden – something like that, or a multitude of other possibilities of association, of course.

You may be a deconstruction worker

But the poet’s wildly swirling stream of consciousness has now carved out a riverbed and the waves are calming down; the third couplet is the first couplet without deletion or addition, and on a technical level perfect:

the savage soldier sticks his head in sand and then complains unto the shoeless hunter / who’s gone deaf but still remains upon the beach where hound dogs bay at ships with tattoed sails heading for the gates of Eden ________

… three perfect fourteeners, suddenly a rhyme scheme AAAB, tightly iambic – the poet’s instinct apparently pushes him towards an antique, tried and tested, though extinct form, a form like the walking music encyclopaedia Dylan knows from the primal versions of folk classics like “John Henry” and “Stagolee”. Just as effortlessly, so it seems, larded with unobtrusive wordplay such as deaf but still, alliterations (savage-soldier-sticks-sand) and mirroring (beach-bay and head in – heading), about which he doesn’t even seem to think twice – as if he was just taking dictation.

In terms of content, a kind of unity also emerges. Not a unity that covers the whole song, but a stanza-internal unity. The second verse already hinted vaguely at a leitmotif, at “metal” as a silver thread (iron – metal – crash), which might have been registered by the associative writing poet, but is not elaborated on further. Presumably just as instinctively, the fast poet builds this third stanza around the leitmotif “predator” (soldier – hunter – hound dog), with the sub-theme “failing communication”; the soldier complains while being inaudible, the hunter is deaf and the hounds bark from the beach helplessly and uselessly at passing ships – where the hounds are undoubtedly just as inaudible as the fierce soldier with his head in the sand.

With that, the bard seems to slowly let go of his original approach, an apocalyptic mosaic à la “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” around a nuclear Holocaust scenario. With some pacing, the images of the second stanza can still be fitted therein, in such a dystopian overview tableau, but that becomes more difficult in this third stanza. We‘re starting to get more on the track of “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)”; a confetti rain of human shortcomings, the condition humaine and the Signs of Time.

On a level below, the real find for the poet himself – or so it appears – is the third variation with “Eden”. After the trees of Eden in the opening couplet and the depths of Eden in the second couplet, now “gates of Eden” bubbles up, which will prove to be a joy. Chosen for playfulness’s sake only, presumably. The novice Beat Poet seeks cut-up-like word combinations, like shoeless hunter and tattooed sails, he seeks a catachresis. So, the ships won’t be heading for New York’s City harbor, or their eternal home, the scrapyard, the rocks, Panama or disaster, nor will they be heading for the Mediterranean, dock, the East Coast, the City of Gold or, for that matter, the Port of Eden. No, thinks the deconstructing poet: they’ll be heading for, let’s see… gates. “The Gates of Eden”…. yes, sounds good.

To be continued. Next up: Gates Of Eden part V: A wedding-cake left out in the rain

——————————

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

“To do anything they wish to do but die” at least for me gives unity to the whole meaning of the song Gates of Eden by taking on a Nietzschean/Twainian perspective that utopian religions assert that you won’t get away by dying because either God or the Devil are going to get you in the ‘afterlife’, the earthly gates to any imagined paradise sealed forever.

* is going to…