- Love Minus Zero/No Limit (1965) part I: Rose of England

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit (1965) part II : A Song Of Ice And Fire

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit (1965) part III: I love you, but you’re strange

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit (1965) part IV: The Order of the Whirling Dervishes

by Jochen Markhorst

V When a sighing begins in the violins

In the dime stores and bus stations People talk of situations Read books, repeat quotations Draw conclusions on the wall Some speak of the future My love she speaks softly She knows there’s no success like failure And that failure’s no success at all

It is only the distinct elegance of the second verse, even more classic than the cool beauty of the opening verse, that reveals the underlying structure of “Love Minus Zero”. On paper, in written form, the poet Dylan, as he often does, conceals the form.

It is only the distinct elegance of the second verse, even more classic than the cool beauty of the opening verse, that reveals the underlying structure of “Love Minus Zero”. On paper, in written form, the poet Dylan, as he often does, conceals the form.

In the official publications, in Writings & Drawings, in Lyrics and on the site, the lyrics are printed in four eight-line stanzas, with no fixed rhyme scheme or metre. Presumably, the musician Dylan dictates the formatting; as it is formatted, each four-line segment falls into the same chord progression:

E My love she speaks like silence, B A E Without ideals or violence, B A E She doesn't have to say she's faithful, F#m A B Yet she's true, like ice, like fire.

Rhyming-wise, however, the lyrics consist not of four octaves, not of four eight-line stanzas, but of four sextets with the classic rhyme scheme AABCCB:

My love she speaks like silence Without ideals or violence She doesn’t have to say she’s faithful Yet she’s true, like ice, like fire People carry roses Make promises by the hours My love she laughs like the flowers Valentines can’t buy her

… a restructuring that can be applied to each of the four octaves, with each strophe “actually” turning out to be a Spanish sextet, a sextet with the rhyme scheme AABCCB. So also like this second stanza:

In the dime stores and bus stations People talk of situations Read books, repeat quotations Draw conclusions on the wall Some speak of the future My love she speaks softly She knows there’s no success like failure And that failure’s no success at all

In Anglo-Saxon literature, Spanish sextets are not too popular. A natural talent like Dylan probably comes to them instinctively, but on the other hand he gives enough hints that Verlaine triggered him. As, in retrospect, in the interview with Jeff Rosen for No Direction Home (2005): “I stayed at a lot of people’s houses which had poetry books and poetry volumes and I’d read what I found… I found Verlaine poems or Rimbaud.”

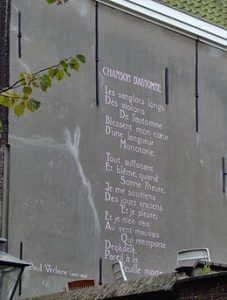

Verlaine is a fan of the Spanish sextet anyway, and if Dylan did indeed immerse himself in Verlaine in the early 1960s, then he inevitably took in one of the absolute highlights of French literary history, Paul Verlaine’s “Chanson d’automne” from 1866. The poem that the Allies used as a code to warn the French resistance that D-Day was about to begin, the masterpiece that was incorporated into songs by Dylan’s colleagues such as Brassens, Gainsbourg and Trenet, and can be found on house walls, monuments and cemeteries throughout Europe;

Les sanglots longs Des violons De l'automne Blessent mon cœur D'une langueur Monotone.

… the first sextet (of three), which Dylan then presumably read in Arthur Symons’ (1902) excellent translation, “Autumn Song”:

When a sighing begins In the violins Of the autumn-song, My heart is drowned In the slow sound Languorous and long

… in which Symons, as in the other sextets, admirably succeeds in saving both the rhyme scheme and the rhythm and the melancholic colour. But even that does not convert the Anglo-Saxon poets. Spanish sextets remain primarily a French form. The English find it more suited for nursery rhymes (“Little Miss Muffet”, for example, also known as “Along Came A Spider”). And the occasional song. “A Boy Named Sue”, written by Shel Silverstein, consists of ten Spanish sestets, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Gimme Three Steps”, and above all: Leonard Cohen’s chef d’oeuvre “Hallelujah”, for which the Canadian bard claims to have written eighty couplets over a period of more than ten years – all Spanish sextets;

Now I've heard there was a secret chord That David played, and it pleased the Lord But you dont really care for music, do you? It goes like this, the fourth, the fifth The minor falls, the major lifts The baffled king composing Hallelujah

Dylan, by the way, will use the same poetic artifice more than twelve years later in a highlight of Street-Legal (1978), in “Where Are You Tonight? (Journey Through Dark Heat)”: there, too, the formatting conceals the fact that the lyrics “actually” consist of Spanish sextets. Incidentally, it also reaffirms a kind of artistic brotherhood with fellow Minnesotan Prince, who does the same in the first quatrain of highlight “Raspberry Beret” – after all, that quatrain can also be restructured into a sextet with the rhyme scheme aabccb:

I was working part time in a five-and-dime My boss was Mr. McGee He told me several times that he didn't like my kind 'Cause I was a bit too leisurely

“Hallelujah”, “A Boy Named Sue”, “Raspberry Beret”… all exceptional songs that approach perfection within the Holy Trinity of Rhyme, Rhythm and Reason – the form seems to bring out the best in talented songwriters.

That also applies to this second verse of “Love Minus Zero”. Literally, it is even more successful than the opening couplet. In terms of content, the poet draws a tighter line between what Dave Stewart seems to mean when he says: “The lyrics start as social insights but then conclude with something romantic and sexy.”

The first five lines “capture a moment in time,” as Stewart calls it, with observations, sketchy impressions of dime stores and bus stations, and in the sixth line the poet then switches to the private, to “my love” and her remarkable aphorism. Stylistically, the poet chooses an extremely melodious wording, with that exuberance of rhyming “-ions”, alliterations (stores-stations, read-repeat) and abundant assonance (people-read-repeat-speak, talk-draw-wall)… it is truly, like “Chanson d’automne”, a dazzling work of art by a brilliant song poet with a perfect mastery of language. If Dylan is not Verlaine’s brother in art, then at least Verlaine’s spirit descended on Greenwich Village for a brief, glorious moment on this spring day 1965.

To be continued. Next up: Love Minus Zero/No Limit part VI: Foul is fair

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

If you would like to read more Untold Dylan also has a very active Facebook group: Untold Dylan.

If you would like to see some of our series they are listed under the picture at the top of the page, and the most recent entries can be found on the home page.

If you would like to contribute an article please drop a line to Tony@schools.co.uk