Early Roman Kings (2012) part I: Humpty Dumpty had a great fall

Early Roman Kings (2012) part II: Anything goes

by Jochen Markhorst

III He had a left like Henry’s hammer

They’re peddlers and they’re meddlers, they buy and they sell They destroyed your city, they’ll destroy you as well They’re lecherous and treacherous, hell bent for leather Each of them bigger than all men put together Sluggers and muggers wearing fancy gold rings All the women going crazy for the early Roman Kings

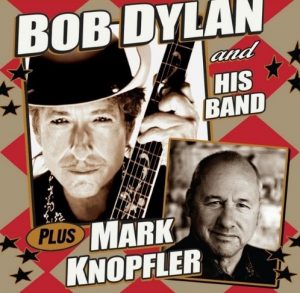

The paths of British guitar god Mark Knopfler do cross Dylan’s career quite often, and each time it results in beautiful music. The first feat is smashing right away: the session work that the then up-and-coming talent does on Slow Train Coming (1979). Producer Jerry Wexler and Dylan wisely let Knopfler do whatever pleases him, resulting in, apart from the ear-catching ornaments in every song, the superb melancholy of “I Believe In You” and especially the irresistible drive of the forgotten gem “Precious Angel”. Dylan is impressed, and a few years later asks Knopfler to produce Infidels, which again yields many beautiful songs, plus one of Dylan’s all-time highlights, the perhaps most beautiful version of “Blind Willie McTell”.

The paths of British guitar god Mark Knopfler do cross Dylan’s career quite often, and each time it results in beautiful music. The first feat is smashing right away: the session work that the then up-and-coming talent does on Slow Train Coming (1979). Producer Jerry Wexler and Dylan wisely let Knopfler do whatever pleases him, resulting in, apart from the ear-catching ornaments in every song, the superb melancholy of “I Believe In You” and especially the irresistible drive of the forgotten gem “Precious Angel”. Dylan is impressed, and a few years later asks Knopfler to produce Infidels, which again yields many beautiful songs, plus one of Dylan’s all-time highlights, the perhaps most beautiful version of “Blind Willie McTell”.

Knopfler does not understand at all why the song is rejected for Infidels, but he is and always will be a devout admirer. Like when he, following in the footsteps of broadcaster Dylan, is allowed to host the British Grove Broadcast series for SiriusXM’s Volume channel. It is an extremely attractive series of 24 broadcasts in which DJ Knopfler, à la Dylan, leads an eclectic journey along “some goodies”, as he calls it, along 263 songs, his musical loves. Dylan as a performer is featured five times, and the DJ also likes to play Dylan covers. The first reverence is right away in Episode 1 (4 March 2020), of course:

“The most important songwriter for me growing up was Bob Dylan. From the age of 12 onwards, really, it hasn’t changed that much. Let me just read from this next song, just a couple of lines: Seen the arrow on the doorpost, saying this land is condemned all the way from New Orleans to Jerusalem – and that was a song Bob wrote called ‘Blind Willie Mc Tell’. We ended up doing that song in the studio and this is Bob on the piano, doing a version, and yours truly on the 12-string guitar. And that’s all it was. That’s a fantastic song, Bob, and what an honour to be part of it. Blind Willie McTell, studio outtake from 1983.”

Bizarrely, the Dire Strait follows his idol not only as a musician and a radio DJ, but also as a crash pilot. At a quarter to eleven in the morning on Monday 17 March 2003, Knopfler, then 53, is riding his Honda along the Grosvenor Road in Belgravia, London, when he is unable to swerve out of the way of a red Fiat Punto that is suddenly turning right. He breaks six ribs and his collarbone and, like Dylan in ’66, cannot perform for months. In fact, after seven months of therapy, he still cannot hold an acoustic guitar. Which he handles with British understatement, by the way: “I thought, oh no, that’s going to be a drag, I’ll just be playing electric guitar for the rest of my life.”

These are not lost months. Knopfler is sitting at his computer, writing the songs for his next solo album, the beautiful Shangri-La. Which is eventually, indeed, recorded in the legendary Shangri-La Studio in Malibu, just around the corner from Dylan’s home – the studio which was set up by The Band and Dylan producer Rob Fraboni, where Richard Manuel lived, where Dylan camped in a tent in the garden, where Clapton recorded No Reason To Cry (1976) with the help of The Band and Dylan, and whatnot.

The record contains, not unusually for Knopfler, drawn-out, epic songs, but this time it is also clear that he has had a lot of time to read. Quotations from the autobiography of Ray Croc, the man behind McDonald’s worldwide success, are used verbatim in the single “Boom, Like That”, “Back To Tupelo” about Elvis’ film career, the murder ballad based on the true story of the 1967 One-Armed Bandit Murder in North East England, where Knopfler grew up, “5:15 A.M.”, but also songs with Dylanesque joy of language in the lyrics, like the ode to Lonnie Donegan, “Donegan’s Gone”;

Donegan's gone Gone, Lonnie Donegan Donegan's gone Stackalee and a gamblin' man Rock my soul in the bosom of Abraham Gone, Lonnie Donegan Donegan's gone

And like the enchanting “Postcards From Paraguay”, played on the good old red Stratocaster:

I never meant to be a cheater But there was blood on the wall I had to steal from Peter To pay what I owed to Paul I couldn't stay and face the music So many reasons why I won't be sending postcards From Paraguay

… which sounds Dylanesque enough, but the Dylan bell goes off earlier, on the opening line already: “One thing was leading to the next, I bit off more than I could chew” – an abrupt opening line like that of Dylan’s “Up To Me” (Everything went from bad to worse, money never changed a thing).

Presumably, however, Dylan himself really pricked up his ears on one of the the record’s stand-out tracks, and a 21st century fan favourite: “Song For Sonny Liston”.

“Song For Sonny Liston” is, in a way, Knopflers “Hurricane”. Remarkably, though, more poetic than that template, and less activist anyway. Knopfler is also aiming for a kind of rehabilitation of a boxer, of the greatest intimidator of all time, the 1962 world heavyweight champion, the unpopular Big Bear, who had to relinquish his world title to Muhammad Ali in 1964. The song is epic, tells of rise and fall, larded with sentimental asides, and is above all Dylanesque; just like his idol, Knopfler draws from old folksongs, he seeks the Golden Mean of Rhyme, Rhythm and Reason, and sometimes lets sound outweigh semantics. Like in the near-perfect chorus:

He had a left like Henry's hammer A right like Betty Bamalam Rode with the muggers in the dark and dread And all them sluggers went down like lead

First, a brilliantly found reference to the folk song “John Henry”, the black nineteenth-century “steel-driving man” with the hammer, embedded in a masterfully alliterating opening line (He had a left like Henry’s hammer). Then a wonderful bridge to Betty Bamalam, which is both an onomatopoetic nod to a boxer and a salute to that other legendary antique work song, to Lead Belly’s “Black Betty” (Whoa, Black Betty bam-ba-lam), and finally the two closing lines which are a joy in rhyme and language.

The same, that joy of rhyme and language, of course applies to this third verse of Dylan’s “Early Roman Kings”. And the suspicion that Dylan borrowed that unusual sluggers and muggers from his music partner Knopfler is strengthened by another remarkable verse line from “Song For Sonny Liston”:

The writers didn't like him the fight game jocks With his lowlife backers and his hands like rocks They didn't want to have a bogey man They didn't like him and he didn't like them Black Cadillac alligator boots Money in the pockets of his sharkskin suits

A boxer, Lead Belly, a Cadillac, “John Henry”, inner rhyme, assonance and alliteration, sharkskin suits… when music archaeologists dig up this song five hundred years from now, “Song For Sonny Liston” will undoubtedly be catalogued as “Folk ballad. Late 20th/early 21st century. Most likely written by the then famous troubadour B. Dylan.”

To be continued. Next up: Early Roman Kings part IV: You can ring my bell, ring my bell

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

I don’t think ‘Henry’s Hammer’ is a reference to John Henry at all. It is a reference to ex British/European/Commonwealth Heavyweight Sir Henry Cooper. Cooper’s main ‘claim to fame’ was that he once knocked Mohamed Ali to the floor during a bout. He had a ferocious left upper cut which became known as ‘Henry’s Hammer’.

Thanks Keith,

I stand corrected with a wonderful fact (I have to admit, to my shame no doubt, I had never heard of Sir Henry Cooper). It just takes a bit of the poetic shine off Knopflers’ lyrics, I’m afraid. I sure hope Betty Bamalam doesn’t turn out to be another famous semi-heavyweight from the 60s.