by Jochen Markhorst

- Cold Irons Bound (1997) part 1: Dear Dr Ralph

- Cold Irons Bound (1997) part 2: To live is to be alone

- Cold Irons Bound (1997) part 3: He who is alone now, will long so remain

- Cold Irons Bound (1997) part 4: Little Boy Lost

- Cold Irons Bound (1997) part 5: A very ornate, beautiful box

VI The cat’s in the stew

Well the fat’s in the fire and the water’s in the tank The whiskey’s in the jar and the money’s in the bank I tried to love and protect you because I cared I’m gonna remember forever the joy that we shared

But here I am in prison, here I am with a ball and chain…it doesn’t end well, for Captain Farrell’s killer. The money he had stolen from the Captain has not been deposited in the bank, but purloined by that treacherous Molly. In cold irons bound he sits in the cell now, dreaming of Molly’s bedroom, and he sings his refrain once more;

But here I am in prison, here I am with a ball and chain…it doesn’t end well, for Captain Farrell’s killer. The money he had stolen from the Captain has not been deposited in the bank, but purloined by that treacherous Molly. In cold irons bound he sits in the cell now, dreaming of Molly’s bedroom, and he sings his refrain once more;

Musha rain dum a doo, dum a da, heh, heh

Whack for my daddy, oh

Whack for my daddy, oh

There’s whiskey in the jar, oh

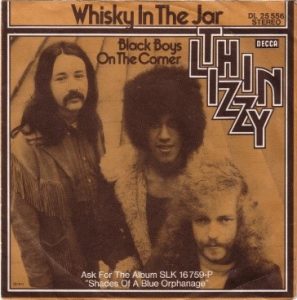

The indestructible Irish classic “Whiskey In The Jar” is an ancient, irresistible folk monument with dozens of versions in circulation. The rock version by Thin Lizzy (1972) is probably the best known and inspired Metallica to do a Grammy-winning heavy metal cover in 1998. And in between, it sneaks into a Dylan song, into the final verse of “Cold Irons Bound”.

The in itself meaningless phrase steers the narrative of “Cold Irons Bound” down a side path. Down the wrong path, to be more precise, on the path to evil. Suddenly, through that highwayman connotation from the old folksong about a criminal who actually ends up in ball and chains, the poet highlights the possibility that in cold irons bound is meant literally, that the narrator has just murdered the woman he so pitifully longs for, and that he is now being carried off – jogging along in chains, already twenty miles on the way to the penal camp.

It is – of course – not unequivocal. The opening, “the fat’s in the fire”, fits in a bit – it does, after all, mean something like trouble ahead, imminent crisis. Squeezing in, however, is not possible with the other two expressions, “water’s in the tank” and “money’s in the bank”. In themselves, again, without much relation to each other or to the text at all. But strangely enough, the accumulation of the four (quasi-) proverbial expressions does actually suggest, without any substantive basis, something like the die is cast, I crossed the Rubicon.

The accumulation, however, seems mainly the product of an improvising, unleashed poet in the zone. Stylistically, but coincidentally also in terms of content, it resembles the enigmatic word processions that Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson is so fond of producing for the crypto-analytical faction of his fan base. Like in the outtake “Living In These Hard Times”, from a somewhat forgotten, beautiful folky highlight of Jethro Tull’s discography, from 1978’s Heavy Horses:

The bomb's in the china. the fat's in the fire. There's no turkey left on the table (…) Well the fly's in the milk and the cat's in the stew. Another bun in the oven --- oh, what to do?

… a beautiful song by the way, that is rightly added as a bonus track on the 2003 reissue (and again on the 2018 40th Anniversary New Shoes Deluxe Edition of course). Demonstrating the same playful enjoyment of language: the alienating mixing of existing expressions (fat’s in the fire, bun in the oven) with catachreses, with non-existent word compounds that nevertheless sound familiar (cat’s in the stew, fly’s in the milk). Triggered, no doubt, by a love of antique nursery rhymes, again similar to Dylan’s – for example, Ian Anderson’s fourth verse begins with:

The cow jumped over yesterday's moon And the lock ran away with the key.

… a not too veiled paraphrase of the age-old “Hey Diddle Diddle” (The Cow jump’d over the Moon / And the Fork ran away with the Spoon). And, to complete the circle, equally inspired by nonsensical refrains like in “Whiskey In The Jar”.

It’s all possible, the nonsensical expressions and the empty metaphors like fly in the milk and water in the tank and whack for my daddy, thanks to the context. “Whiskey in the jar” becomes something like those were the days. Ian Anderson embeds his invented sayings in a portrait of a life full of misfortune, making something like cat’s in the stew suddenly meaningful. And Dylan offers a fitting meaning for his linguistic finds in the lines that follow:

I tried to love and protect you because I cared I’m gonna remember forever the joy that we shared

So: “our good times are over now and out of reach”, something like that. Like water in a tank, like money in a bank, like whiskey in a jar and like fat in a fire. Maybe not entirely watertight, but what the heck – Dylan shakes the lyrics out of his sleeve in a few minutes, doesn’t feel like polishing them, records it straight away, and above all: it sounds good. And you want your songs to sound good (Nobel Lecture, 2017).

VII Cosmic waste and space debris

Looking at you and I’m on my bended knee You have no idea what you do to me I’m twenty miles out of town in cold irons bound

The sketchy, improvised impression of the last verse is confirmed by the last refrain. I’m gonna remember forever the joy that we shared is a farewell – it fits badly with the subsequent present tense of the chorus lines. But in terms of content, it once again gives food for the thought that “Cold Irons Bound” subcutaneously is a murder ballad: the scene described is a copy of the repentant murderess Frankie from “Frankie And Johnny”;

She said, “Oh, Mrs. Johnson Oh, forgive me please Well I killed your lovin' son, Johnny But I'm down on my bended knees I shot my man, but he was doin' me wrong, so wrong.”

Dylan uses the image in his adaptation of the song (“Frankie & Albert”, on Good As I Been To You, 1992), but shifts it to an even more dramatic scene:

Frankie got down upon her knees, took Albert into her lap. Started to hug and kiss him, but there was no bringin' him back. He was her man but he done her wrong

… the death scene. After which Frankie is taken away – bound in cold irons, no doubt.

Not too far-fetched. “Frankie & Johnny” and its many adaptations (Leadbelly, Mississippi John Hurt, Elvis) is somewhere at the front of Dylan’s inner jukebox, and echoes thereof easily seep in, when the songwriter is in a creative daze and has a murder ballad up his sleeve. But who knows – Dylan’s meandering mind may also have led him past Muddy Waters, triggered by the preceding money in the bank (from Muddy’s “You Can’t Lose What You Ain’t Never Had”: I had money in the bank / I got busted, boys, ain’t that sad?), which then might lead Dylan to Muddy’s ode to his wife, to “Little Geneva” from 1949:

I want to see Geneva so bad, so bad Right now I'm on my bended knee

Less fitting in a possible murder-context of “Cold Irons Bound”, but on the other hand: almost all bended knees in Dylan’s repertoire and in Dylan’s record collection are of desperate men begging their (living!) wives to stay. George Jones’s “There Ain’t No Grave Deep Enough”, John Lee Hooker’s “Wednesday Evening Blues”, Blind Willie McTell’s “Broke Down Engine” (which Dylan records for World Gone Wrong in 1993), Little Richard’s “Can’t Believe You Wanna Leave”… no, that record cabinet is filled to the brim with pitiful men on bended knees, but none of them is a murderer – they are all suckers humiliating themselves in front of an apparently dominant, but most of all living woman.

A remorseful murderer or a pathetic sucker – it seems Dylan doesn’t know either at the time of conception. “It’s one of those where you write it on instinct. Kind of in a trance state. Most of my recent songs are like that,” as Dylan says about “I Contain Multitudes” in 2020, and: “They just fall down from space.”

Okay, the latter is perhaps a bit too woolly. It does seem quite likely, after all, that large parts of Dylan’s songs do not so much come from outer space, but rather from his own record collection. Which is a good thing, by the way; falling-out from Dylan’s record cabinet undoubtedly sounds much better than incoming space junk.

And you do want your songs to sound good.

————————–

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

Little structuralist lost …. he’s takes himself so obdurately

…. must be the sound that matters….

Or perhaps, as Weir’d say, the narrator has a character flaw

When it comes down to the arrangement of words, the songwriter has the final say of what he chooses among the ‘random’ fragments that he uses.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/123/Cold-Irons-Bound

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.