by Jochen Markhorst

I An absolutely astonishing thing for a boy of twenty to have written

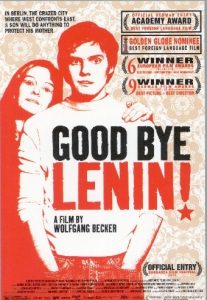

Ostalgie, the contraction of “Ost” (East) and “Nostalgie”, is the beautiful portmanteau word that emerges from 1991 to express the longing for life in Ostdeutschland, in East Germany before the fall of the Wall. The fall of the Wall, 9 November 1989, initially led to euphoria and to an exaggerated expectation of all the blessings that the wealth of the capitalist West would bring – the sobering, slowly sinking realisation that it is not all moonlight and roses, this capitalist welfare paradise of prosperity, is quite disappointing. The disappointment is combated with a return to the products and music of the GDR era at Ostalgie-Party’s and from 2000 the entertainment industry joins in. Television series set in an idealised GDR, bands specialising in East German hits, and films such as the witty Sonnenallee and especially the brilliant Good Bye Lenin! (Wolfgang Becker, 2003). That film, in which the main character goes to extremes to save his mother from the shock of finding out that the Wall has fallen, drives Ostalgie to unprecedented heights and makes the demand for old GDR products explode.

Ostalgie, the contraction of “Ost” (East) and “Nostalgie”, is the beautiful portmanteau word that emerges from 1991 to express the longing for life in Ostdeutschland, in East Germany before the fall of the Wall. The fall of the Wall, 9 November 1989, initially led to euphoria and to an exaggerated expectation of all the blessings that the wealth of the capitalist West would bring – the sobering, slowly sinking realisation that it is not all moonlight and roses, this capitalist welfare paradise of prosperity, is quite disappointing. The disappointment is combated with a return to the products and music of the GDR era at Ostalgie-Party’s and from 2000 the entertainment industry joins in. Television series set in an idealised GDR, bands specialising in East German hits, and films such as the witty Sonnenallee and especially the brilliant Good Bye Lenin! (Wolfgang Becker, 2003). That film, in which the main character goes to extremes to save his mother from the shock of finding out that the Wall has fallen, drives Ostalgie to unprecedented heights and makes the demand for old GDR products explode.

Ostalgie, in short, is not only for works of art a fertile emotion to exploit. However, the assimilation of the term contributes to a blurring of the actual, original meaning of nostalgia – it has become more and more something like melancholy, the bittersweet longing for the “good old days”. Originally, however, “nostalgia” denotes the feeling that Dylan expresses so masterfully and poetically in “I Was Young When I Left Home”: the pain of realising that you have lost something dear to you forever. As the Greek origin reveals; nostos = return and algos = sadness, pain, suffering.

Only one recording exists, Dylan never played it live. That one recording was made in Minneapolis, in the flat of friend Bonnie Beecher. On that December day in 1961, no less than 26 songs are put on a tape, which is called the Minnesota Hotel Tape (Bonnie’s flat was called “Beecher Hotel” in the circle of friends). On the soundtrack to No Direction Home, which was released in 2007 as The Bootleg Series Vol. 7, Dylan announces the song and we can hear that he appropriates it: I sorta made it up on a train. And he has an opinion as well: This must be good for somebody, this sad song. I know it’s good for somebody. If it ain’t for me, it’s good for somebody.

“I sorta made it up” is sorta about right. Dylan copies almost entirely two verses of “500 Miles” by folk singer Hedy West (the Not a shirt on my back and the If you miss the train I’m on verses), the structure is the same and he borrows a few fragments from the melody. This “500 Miles” is the song of a down and out vagabond, consumed by homesickness.

Dylan adds more melodrama, stepping into the shoes of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15, 11-32), but without a happy end. This runaway remains lost; mother dead and gone, sister on the wrong track, father in trouble… no, I can never go home again. By the way, West’s song is also an adaptation: she nibbles 400 miles off the folk-traditional “900 Miles” but spares enough that eventually trickles through to Dylan’s adaptation.

A line like You will hear that whistle blow a hundred miles, for instance, is already in that original 900 miles version. A mutilated version thereof, to complete the circle, is played by Dylan in 1967 in the Big Pink and can be heard on The Basement Tapes. In it, only the line ‘Cause I’m 900 miles from home and the melody (more or less) remain. A playful Dylan further shuffles the old negro spiritual “Mary Don’t You Weep” and a lot of spontaneously made-up verse lines into the song.

The second part of Dylan’s introductory talk is telling. “This must be good for somebody. If it ain’t for me, it’s good for somebody.” Which is in line with the modest self-image that emerges from the autobiography Chronicles Vol. 1; Dylan often refers to himself as a conduit – it’s The Song that matters, not the singer. He himself is just 20 when he sings this. Far too young and inexperienced, one might say, to be able to identify with the protagonist here. The protagonist is a tired, beaten-up over-50-year-old who has the right to be nostalgic and to tell his sad story. Of course, tenderfoot Dylan is an extremely gifted natural. It’s still amazing, though.

Marianne Faithfull expresses a similar, admiringly meant, amazement relating to the creation of “As Tears Go By”:

“I was never that crazy about “As Tears Go By.” God knows how Mick and Keith wrote it or where it came from. It’s a great fusion of dissimilar ingredients: “The Lady of Shalott” to the tune of “These Foolish Things.” The image that comes to mind for me is the Lady of Shalott looking into the mirror and watching life go by. It’s an absolutely astonishing thing for a boy of twenty to have written. A song about a woman looking back nostalgically on her life. The uncanny thing is that Mick should have written those words so long before everything happened. It’s almost as if our whole relationship was prefigured in that song.”

“An absolutely astonishing thing for a boy of twenty to have written.” Beautifully phrased by the as always eloquent Faithfull, and she indirectly puts her finger on the sore spot: for all the beauty of the song, the gap between the unmistakably pure, innocent youthfulness of the singer and the nostalgic, autumnal ripeness of the protagonist is insurmountable. Marianne is simply too young and too green to cover up that gap. She sings heartbreakingly melodic and high – totally out of character, in other words. Later, as her young voice fades, everything falls into place, by the way. On Negative Capability, the album she will record in 2018 with Nick Cave and her current life partner Warren Ellis, she sings a fairly definitive, withered version.

A highlight that is even surpassed by the bare recitation of the lyrics, in September 2021.

In 2020, the grand old lady experiences another low point in her constant, endless succession of health problems and physical discomforts when she suffers pneumonia on top of a Covid-19 infection. As usual, she gets back on her feet, again as usual against all odds. In September 2021, La Faithfull is staying at Denville Hall, a retirement home for performing artists. In the garden, sitting in a wheelchair next to an oxygen machine, she receives journalists to promote her new album She Walks In Beauty. On that album, she doesn’t sing, but recites, over a sober carpet of murmuring muzak, eleven poems by the Romantics, by poets like Keats, Shelley and Wordsworth. The album concludes with, very fittingly, Tennyson’s “The Lady Of Shalott”, the poem she already linked to “As Tears Go By” in her first autobiography (1994). It may explain her receptivity to the somewhat silly question from a Dutch journalist whether she would care to recite the lyrics of her first hit, here in the garden of Denville Hall. La Faithfull half-heartedly objects (“But this is not a poem”), but then does it anyway – somewhat surly, presumably mainly motivated by the urge to put the whole thing behind her, gasping for oxygen in between… and now suddenly a real 74-year-old lady is speaking, interpreting the words of a fictional 74-year-old lady.

Faithfull reciting As Tears Go By at 01’50”:

The fantasy of how much beauty and power Dylan’s “I Was Young When I Left Home” would gain if some silly journalist could persuade 80-year-old Dylan to perform the song again, sixty years later, is tantalizingly attractive. But it doesn’t seem to be in the cards. A Faithfull-like reworking, an “I Was Young When I Left Home Revisited”… we can only dream. “I’m not a nostalgic person,” says Dylan, in his Post-MusiCares Conversation with Bill Flanagan in 2015. And in October 2021, another well-informed source, oldest son Jesse Dylan, provides a verbatim confirmation of that self-analysis in the Times interview, when the interviewer asks him if he and his dad ever look back on the Sixties. “He’s not a nostalgic person, he’s always looking forward to the next thing,” Jesse says.

On the other hand… “Highway 61 Revisited” is still on the set list often enough. And Highway 61 does lead to Duluth, does lead home…

To be continued. Next up: I Was Young When I Left Home part II: Different doors

——-

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

Nostalgia isn’t what it used to be

It wasn’t simply the writing of the song, it was the singing.

At age 20, Dylan sang with a voice that came from the ages.

It’s not “this sad” song, it’s “this here” song.

Thanks Tom, you’re right.