by Jochen Markhorst

I They going down 61 Highway

Mozart, Van Gogh, Garrincha, Charley Patton, Nick Drake, Baudelaire… our history is rich with exceptionally gifted artists who, for various reasons, do not manage to cash in on their otherworldly talent and die penniless and forgotten. Especially painful in that shameful list are the artists who live long enough to see others make use of their work and become rich and famous with it. Arthur Crudup, of course, is a prime example. The man who wrote “That’s Alright, Ma” and “My Baby Left me”, the songs that catapulted Elvis into the stratosphere. Crudup was eventually fobbed off with $10,000, three years before his death in 1974, after years of lawyer’s sabre-rattling and embarrassing legal wrangling.

Mozart, Van Gogh, Garrincha, Charley Patton, Nick Drake, Baudelaire… our history is rich with exceptionally gifted artists who, for various reasons, do not manage to cash in on their otherworldly talent and die penniless and forgotten. Especially painful in that shameful list are the artists who live long enough to see others make use of their work and become rich and famous with it. Arthur Crudup, of course, is a prime example. The man who wrote “That’s Alright, Ma” and “My Baby Left me”, the songs that catapulted Elvis into the stratosphere. Crudup was eventually fobbed off with $10,000, three years before his death in 1974, after years of lawyer’s sabre-rattling and embarrassing legal wrangling.

His genius seems to have touched Dylan, too. Apart from “It’s Alright, Ma”, which Dylan will continue to play over the years (including with Johnny Cash in the studio, 1969), a dusty Crudup single also seems to have been among the “reference records”, the records Dylan gives as homework to producer Daniel Lanois and studio staff before recording Time Out Of Mind and “Dirt Road Blues”. Like engineer Mark Howard, who tells Uncut:

“All these old blues recordings, Little Walter, guys like that. And he’d ask us, ‘Why do those records sound so great? Why can’t anybody have a record sound like that anymore? Can I have that?’ And so, I say, “Yeah, you can get those sounds still.”

Similar to how engineer Chris Shaw describes his experiences of searching for the right sound: “He might say, ‘Well, I’m kinda hearing this like this old Billie Holiday song.’ And so we’ll start with that, the band will actually start playing that song, try to get that sound, and then he’ll go, ‘Okay, and this is how my song goes.’ It’s a weird process.” And fitting with what Lanois reveals about his preparations for Time Out Of Mind:

“I did a lot of preparation with Pretty Tony in New York City. I listened to a lot of old records that Bob recommended I fish out. Some of them I knew already – some Charley Patton records, dusty old rock’n’roll records really, blues records. And Tony and I played along to those records.”

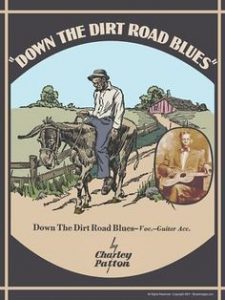

Charley Patton is, of course, a spirit that hovers over Time Out Of Mind anyway, and especially over its successor «Love And Theft» (2001). In lovingly stolen riffs (“Highlands”), complete songs (“High Water”), fragments of lyrics and, indeed, sound. Patton’s stamp on “Dirt Road Blues” seems rather obvious. After all, one of Patton’s best-known songs is the smashing “Down The Dirt Road Blues” from 1929, with the opening lines expressing the same, world-weary state of mind as Dylan’s protagonist:

I'm goin' away to a world unknown I'm goin' away to world unknown I'm worried now, but I won't be worried long

https://youtu.be/cuICVsaxJxc

… and, obviously, the same classic blues text structure – each verse a repeated opening line, followed by a rhyming closing line. And coincidentally, almost as many words even (170 vs. 179). Yet this doesn’t seem to be the “reference record” around which Dylan constructs his song – the sound doesn’t match. In this respect, Crudup’s adaptation, “Dirt Road Blues”, which he recorded in Chicago in October 1945, is closer. From which, by the way, Arthur will lift the second verse, turning it into the Big Bang of rock’n’roll:

Well now, that's all right now, mama, that's all right for you That's all right, baby, any way you do Now, I ain't goin' down, baby, by myself You know, the one that I love, moving down with someone else

… the verse with the lyrics, the drive and the melody that will become “That’s All Right Mama”, rock’n’roll’s ground zero, which Crudup will record eleven months later as “That’s All Right”, a B-side to “Crudup’s After Hours”. That music-historical fact of Crudup’s “Dirt Road Blues” eclipses everything else, but in 1997 Dylan seems to be particularly touched by the sound;

…at least, Dylan takes the stomp, the rhythm, the guitar pattern and the rattling, shrill guitar sound with him. The atmosphere is different, though – Dylan’s song is spooky. Thanks to a fairly simple artifice: reverb on Dylan’s vocals and the ethereal, wispy, unearthly organ sound of Augie Meyers’ keys.

Dylan is asked about it, in interviews after the release of Time Out Of Mind. By Newsweek‘s David Gates, for example. In the week of 21 September 1997, a week before the release of Time Out Of Mind, three journalists are invited, one after the other, to a Santa Monica hotel suite. They have already heard the recordings, and Gates did notice both the overall desolate theme and the extraordinary sound. “It is a spooky record,” Dylan agrees, “because I feel spooky. I don’t feel in tune with anything.”

Bleak, lugubrious words. Spoken by a man who is still recovering from an encounter with Death four months earlier – that viral infection in the sac around the heart. Who, the doctors explain, presumably contracted his infection by inhaling fungal spores down some dirt road in Indiana, Tennessee or Illinois. Who declares after his discharge from hospital: “I really thought I’d be seeing Elvis soon.” And Patton, Robert Johnson and Arthur Crudup, we might add. That heavenly choir would probably have had strike up “Dirt Road Blues” as welcome song. Although Crudup most likely would have called for his own “Death Valley Blues”:

Tell all the women Please come dressed in red They going down 61 Highway That's where the poor boy he fell dead

“Man, you must be puttin’ me on,” Dylan probably would have said, before joining in.

To be continued. Next up: Dirt Road Blues part 2

——————

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

One of the many extraordinary things about that Charlie Patton recording is the way he adds an extra two beat bar at the end of some of the lines, meaning it is not a 12 bar blues anymore. He’s not the only artist of the era to do it, but for anyone who hears to pulse of the music as a central part of what is going on, it is most disconcerting.