by Jochen Markhorst

II The troublingest woman I ever seen

Gon’ walk down that dirt road, ’til someone lets me ride

Gon’ walk down that dirt road, ’til someone lets me ride

If I can’t find my baby, I’m gonna run away and hide

They do walkabout, the poor protagonists of Dylan’s Time Out Of Mind. “I’m walking through streets that are dead” is the opening line of the album (“Love Sick”), “Standing In The Doorway”, the song after “Dirt Road Blues” starts with I’m walking through the summer nights, then comes “Million Miles” and “Tryin’ To Get To Heaven”, in which the I-person has to walk through the middle of nowhere, to wade through high muddy water and is just going down the road feeling bad, and like this, it goes on. In “Not Dark Yet” he follows the river, he is twenty miles out of town in Cold Irons Bound, he goes to the end of the earth To Make You Feel My Love and the album’s closing track is a restless wanderer again, with his heart in the Highlands.

They do walkabout, the poor protagonists of Dylan’s Time Out Of Mind. “I’m walking through streets that are dead” is the opening line of the album (“Love Sick”), “Standing In The Doorway”, the song after “Dirt Road Blues” starts with I’m walking through the summer nights, then comes “Million Miles” and “Tryin’ To Get To Heaven”, in which the I-person has to walk through the middle of nowhere, to wade through high muddy water and is just going down the road feeling bad, and like this, it goes on. In “Not Dark Yet” he follows the river, he is twenty miles out of town in Cold Irons Bound, he goes to the end of the earth To Make You Feel My Love and the album’s closing track is a restless wanderer again, with his heart in the Highlands.

Already after one verse “Dirt Road Blues” seems to be a similar lament as the lamentations of the other lamenters on this album; scourged by heartbreak, abandoned by the woman he can’t live without. Not that those first few words are that explicit – but after about seventy years of blues tradition, it’s an educated guess; most of us have been conditioned to the point that walking down the dirt road can only mean: that poor sucker just lost the love of his life. A Pavlovian association that can be traced all the way back to Tommy Johnson, presumably.

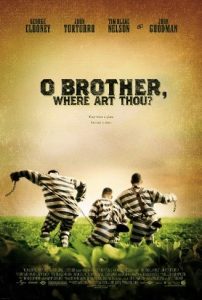

“Sing in me, O Muse, and through me tell the story.” The Odyssey quote with which Dylan concludes his Nobel Prize lecture is also the opening of the brilliant 2000 Coen Brothers film O Brother, Where Art Thou. Dylan publicly expresses his great admiration for the film, which has a lot to do with George Clooney, but even more with the soundtrack. And with the wildly colourful script of course, which playfully, unobtrusively and extremely imaginatively incorporates hints and nods to classic films, Homer, American history and music. Like the role for Tommy Johnson:

HITCHHIKER: Thank you fuh the lif’, suh. M’names Tommy. Tommy Johnson.

Delmar is genuinely friendly:

DELMAR: How ya doin’, Tommy. I haven’t seen a house in miles. What’re you doin’ out in the middle of nowhere?

Tommy is matter-of-fact:

TOMMY: I had to be at that crossroads las’ midnight to sell mah soul to the devil.

Indeed, of the legendary blues Founding Father the story was spread that he owed his exceptional guitar skills to a deal with the devil on the crossroads, a story that somehow got transferred to Robert Johnson. In the film, the Soggy Bottom Boys take him to the studio, where, with Tommy as guitarist, they record an irresistible version of “Man Of Constant Sorrow”, the song that is also somewhere in Dylan’s personal Top 40.

Dylan got to know Tommy Johnson’s work as early as 1960 in Minnesota, he tells in Chronicles (“where I first heard Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Blake, Charlie Patton and Tommy Johnson”), and as a DJ in Theme Time Radio Hour, he dwells on him more extensively:

“Along with Son House and Charley Patton, no one was more important to the development of Delta Blues than Tommy Johnson. And long before the stories about Robert Johnson, selling his soul at the crossroads, those same stories were told about Tommy Johnson. His live performances, where he would play guitar behind his neck, while hollering the blues at full volume, are legendary. Unfortunately, his addiction to alcohol was so pronounced, that he was often seen drinking sterno and even shoe polish, strained through white bread, when whiskey wasn’t available.”

… introducing “Cool Drink Of Water Blues”, episode 23, Water. Dylan recalls the bizarre-appearing fact that Tommy even drank sterno and shoe polish to satisfy his alcohol addiction, but it does seem to be a true story; several sources report this disturbing biographical fact – not least Tommy Johnson himself:

Cryin', canned heat, mama Sho', Lord, killin' me Take alcorub to Take these canned heat blues

… the opening couplet of “Canned Heat Blues” from 1928, in which Tommy complains that rubbing alcohol, the at least as poisonous isopropyl, is supposed to save him from the canned heat blues, from the sickly desire for that thoroughly toxic burning paste Sterno. Repulsive, but who knows – maybe it contributed to the emergence of immortal pillars of the blues, to monuments such as “Big Road Blues” that via Floyd Jones’s “Dark Road” from 1951 eventually evolved into “On The Road Again”.

“On The Road Again” (1968) is one of the biggest hits for the Californian blues rock band Canned Heat, the band that already honours Tommy Johnson in its choice of band name. And with this hit, the band contributes to the continuity of that image, of the image that walking down the road evokes;

Well, I'm so tired of crying But I'm out on the road again I'm on the road again I ain't got no woman Just to call my special friend

… the image of the pitiful, love sick dupe. The image carved in 1928 by Tommy Johnson’s “Big Road Blues”;

Cryin', ain't goin' down this Big road by myself A-don't ya hear me talkin', pretty mama? Lord, ain't goin' down this Big road by myself

But from that other monument, the song that DJ Dylan plays in the twenty-first century, “Cool Drink Of Water Blues”, we hear echoes in Dylan’s “Dirt Road Blues” as well; the simple blues lick that carries the song is a sped-up copy of Tommy Johnson’s lick. Another song that reverberates for decades, by the way; Howlin’ Wolf’s 1956 hit “I Asked For Water” is Wolf’s take on the same song.

… which the DJ knew all along, of course:

“Cool Drink Of Water Blues” was amped up in the fifties and became one of the great Chicago blues tracks when it was recorded by one of his biggest admirers, Howlin’ Wolf, under the name “I Asked For Water, She Brought Me Gasoline”

Not an easy-going girl either, that one. “That’s the troublingest woman, that I ever saw,” as Howlin’ Wolf says. Sooner rather than later, that boy shall go down the road too. But: by car, this time.

To be continued. Next up: Dirt Road Blues part 3

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

———-

Untold Dylan was created in 2008 and is published daily – currently twice a day – sometimes more, sometimes less. Details of some of our series are given at the top of the page and in the Recent Posts list, which appears both on the right side of the page and at the very foot of the page (helpful if you are reading on a phone). Some of our past articles which form part of a series are also included on the home page.

Articles are written by a variety of volunteers and you can read more about them here If you would like to write for Untold Dylan, do email with your idea or article to Tony@schools.co.uk. Our readership is rather large (many thanks to Rolling Stone for help in that regard). Details of some of our past articles are also included on the home page.

We also have a Facebook site with over 13,000 members.