by Jochen Markhorst

I From Sacramento to Bangor, Maine

Wanted man in California, wanted man in Buffalo

Wanted man in Kansas City, wanted man in Ohio

Wanted man in Mississippi, wanted man in old Cheyenne

Wherever you might look tonight, you might see this wanted man

Dylan’s fascination with wanted men, with killers in particular, has been known since the early 60s, and is uncomfortable to this day. The 1975 ode to mafia assassin Joseph “Joey” Gallo is one of the low points in that respect, not to mention the propagandistic nonsense Dylan sings about John Wesley Hardin, the repulsive psychopath who murdered dozens of innocent people for the slightest reason (because they snored, for instance): “He was never known to hurt an honest man”, to quote just one blatant lie, and “But no charge held against him could they prove” (“John Wesley Harding”, 1967).

Dylan’s fascination with wanted men, with killers in particular, has been known since the early 60s, and is uncomfortable to this day. The 1975 ode to mafia assassin Joseph “Joey” Gallo is one of the low points in that respect, not to mention the propagandistic nonsense Dylan sings about John Wesley Hardin, the repulsive psychopath who murdered dozens of innocent people for the slightest reason (because they snored, for instance): “He was never known to hurt an honest man”, to quote just one blatant lie, and “But no charge held against him could they prove” (“John Wesley Harding”, 1967).

Whitewashings like “poetic freedom” or “irony” do not make it any less distasteful. Moreover, off-song utterances also give reason to think that Dylan has a peculiar blind spot for the inappropriateness of admiring unscrupulous butchers like Jesse James, John Wesley Hardin and Joe Gallo, and the anecdote told by scriptwriter Rudy Wurlitzer to Popmatters journalist Rodger Jacobs in 2009 is illustrative and rather worrying in this regard.

Wurlitzer, incidentally indeed a great-grandson of Rudolph Wurlitzer, the jukebox guy, attracted attention thanks to his script for the cult classic Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), the only film to feature James Taylor (in a leading role even, as “The Driver”, with a supporting role for Beach Boy Dennis Wilson as “The Mechanic”). The script impresses, is printed in its entirety in the April 1971 issue of Esquire, and is noticed by director Peckinpah. “Bloody” Sam then asks Wurlitzer to write the script for his next western, Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid, which apparently comes to Dylan’s attention.

“The script was already written when Bob came to see me in my apartment on the Lower East Side of New York. He said that he had always related to Billy the Kid as if he was some kind of reincarnation; it was clear that he was obsessed with the Billy the Kid myth.”

Wurlitzer, who at first naturally thinks Dylan is interested in providing the soundtrack, learns to his surprise that Dylan would like to play in the movie. One phone call to producer Gordon Carroll is enough (Carroll, of course, recognises the commercial value of a film poster with Dylan’s name on it), and Wurlitzer invents an insignificant supporting role (“Alias”) on the spot, and, still back home in New York, quickly writes a few extra scenes into the script.

The rest is history, but Wurlitzer’s outpouring about Dylan’s obsession with Billy The Kid remains somewhat underexposed – though it really is not that insignificant. It places yet another question mark over Dylan’s judgement or, perhaps more painfully, an irrevocable tick in the “rather naïve” box on the list of Dylan’s intellectual qualities.

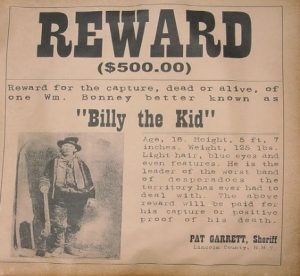

An “obsession with the Billy The Kid myth” and a sense that he is “a kind of reincarnation” of the legendary outlaw suggests that Dylan is confusing romanticised biographies of the desperado with historiography. The dry, factual historiography is quite comprehensive and well-documented, and leaves little doubt about the nature of Henry McCarty alias William H. Bonney alias Billy The Kid; robbing shops from the age of 15, aggressive horse thief, quarrelsome gambler and (at least) eight-time murderer, who needlessly and with apparent pleasure also kills unarmed opponents – there really isn’t much admirable or romantic about the actual life story of Billy The Kid.

If Dylan feels any kinship at all, it almost certainly has to be with one of Billy’s many film incarnations. The Law vs. Billy the Kid (1954, starring Scott Brady), for instance, or 1958’s The Left Handed Gun, with Paul Newman. And songs like Woody Guthrie’s version of “Billy The Kid”, and otherwise that of Marty Robbins (on one of Dylan’s favourite albums, Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, 1959), will only have confirmed him in Billy’s heroic, ill-fated image;

I rode down the border and robbed in Juarez I drank to the maidens, the happiest of days My picture is posted from Texas to Maine And women and riding and robbing's my game

… subject matter, myth-making and word choice that all lead him to the song he pulls out of his stetson in few minutes for Johnny Cash in 1969: “Wanted Man”.

The song is not overly ambitious; in fact, no more than a list song over a ten-a-penny chord progression (the time-honoured Johnny Cash favourite, C-D-G-F-C repeating chord sequence), with an equally unspectacular melody. The trigger for the song doesn’t seem too mysterious either: San Quentin. The song is first tried, and presumably written, on 18 February 1969. Six days later, 24 February, Cash is expected in California, at San Quentin State Prison, for the legendary prison concert.

In fact, Dylan’s inspiration seems to have been fed far more extensively by Cash’s touring schedule than this single, legendary concert at San Quentin. A glance at the Man in Black’s tour history does ignite more than one aha-experience:

- 24 February – 12 March ’69 – California

12 October ’69 – Buffalo

17 March ’68 – Kansas City

27-28 August’69 – Ohio

1 December ’69 – Mississippi

14 September ’68 – Colorado

13 August ’70 – Georgia

13 September ’68 – El Paso

21-21 October ’69 – Shreveport

12-13 September ’69 – Abilene

15-18 September ’69 – Albuquerque

14 November ’69 – Syracuse

… remarkably many of the place names Dylan lists in “Wanted Man” can be found in Cash’s tour schedule. Twelve out of 16 – that’s a bit too many to be coincidental. The US has over 19 thousand towns and cities, with Cash performing in 36 of them in 1969, so the chance of Dylan incorporating twelve of them in his song is microscopically small. Thirteen even, if you cheat a bit;

Then I went to sleep in Shreveport, woke up in Abilene

Wonderin’ why the hell I’m wanted at some town halfway between

Exactly halfway between Shreveport and Abilene lies Dallas – where Cash performs on 29 November 1969. Incidentally: still here in Nashville, probably at that same little table, Dylan writes “Champaign, Illinois” as well, for the guitarist on duty during this same session, for Carl Perkins – Cash plays 4 October 1969 in Champaign, Illinois.

All in all, it begins to look very much like Cash’s calendar indeed is on the little table at which Dylan quickly writes his song for his friend. Although Take 1, on The Bootleg Series Vol. 15 1967-1969: Travelin’ Thru (2019) suggests that the song has not literally been completely “written” at that point; Cash has only a basic idea of the lyrics and is just guessing at the place names. “Hibbing” he shouts, for example, gleefully cheeky, and “Duluth”. Apparently, he does not yet have a written-out full version of the lyrics. Which are, by the way, very different from the final, official lyrics anyway:

Wanted man in Indiana, wanted man in Ohio Wanted man in Texarkana, wanted man in Mexico Wanted man in Sacramento, wanted man in old Cheyenne Wherever you may look tonight, you may see this wanted man

… with Dylan himself in turn also hopelessly jumbling the lyrics, when repeating this opening couplet – which then turns out to be intended as a chorus:

Wanted man in Sacramento, wanted man in Tennessee

Wanted man in Oklahoma, wanted man in… ehmm…

[“Muskogee?” Cash guesses]

Wanted man in Indiana, wanted man in old Cheyenne

Wherever you might look tonight, you may see this wanted man

And in the continuation Dylan, clearly à l’improviste, calls out place names like Milwaukee, Minneapolis and Missouri, and an audibly amused Cash does not lag behind. “Bangor, Maine”, “Seattle”, “Jackson”, “Bristol”, “Kingston”, “Norfolk”… again all place names where he has either performed recently or will perform soon. Yes, by now the conclusion seems inescapable: during this semi-improvised Take 1, both men are peeking at the same tour schedule, at Johnny Cash’s 1968-69 tour schedule. “Gate City”, which Cash playfully calls out at the end, is an unsightly little town in Virginia (about two thousand inhabitants) where the Man In Black won’t play until August 1971, so that’s not the trigger; that would be his wife June, also present in the studio – she is from there.

Anyway: in six days, in a California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation State Prison for Men, Cash will premiere the final version of “Wanted Man”.

To be continued. Next: Wanted Man part 2: I shot a man in Reno

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

Joshen do you believe that Dylan actually confuses the real murderous history of yesterday’s and today’s outlaws whom he deliberately tranforms into antiEstablishment ‘Robin Hood’ Americana archetypes??

In contrast to many Establishment ‘heroes’ like Davy Crockett who were actually defending slavery at the Alamo.

Raindrops keep falling on your head!

Hey Jochen,

Gate City is a nice, pretty little town.

Ah, mea culpa & how awkward, WJB; I thought “unsightly” means “very small”.

I stand corrected. Thanks!

” a sightly little town”

But Willie had a heart of gold

And this I know is true

He supported all his children

And all their mothers too

He wore no rings or fancy things

Like other gamblers do

He spread his money far and wide

To help the sick and poor

(Bob Dylan: Rambling Gambling Willie)

John Wesley Harding

Was a friend to the poor

He travelled with a gun in every hand

He opened many a door

But he was never known to hurt an honest man

(Bob Dylan: John Wesley Harding)

King of the streets

Child of clay

Joey, Joey

What made them want to come

And blow you away

(Bob Dylan: Joey ~ Dylan/Levy)