- Girl From The North Country (1963) part 1: He was a real magpie

- Girl From The North Country (1963) part 2: La Gazza Ladra

by Jochen Markhorst

III Whatever “country” is

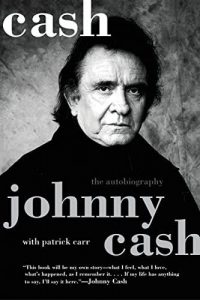

“John R. Cash was an American country singer-songwriter.” Thus opens the English Wikipedia page on Johnny Cash, and so do the French, German, Dutch, Russian, Chinese and about 90 more Wikipedia pages: Cash was first and foremost a country artist.

“John R. Cash was an American country singer-songwriter.” Thus opens the English Wikipedia page on Johnny Cash, and so do the French, German, Dutch, Russian, Chinese and about 90 more Wikipedia pages: Cash was first and foremost a country artist.

The Spanish calls him el Rey de la Música Country, the Portuguese personificação do country, and actually only the Letzenburgische (Luxembourg) does not mention a style of music in the first paragraph, but only mentions it at the end of the second paragraph:

Säi musikalesche Spektrum ass vun den 1950er Jore mat Country, Gospel, Rockabilly, Blues, Folk a Pop bis zum Alternative Country am Ufank vum 21. Joerhonnert gaangen.

… so “country” still does come first. Whereon one could have an opinion, and Johnny Cash himself struggles with it too, in his autobiography. Firstly, with the term itself. “When music people today,” Cash philosophises, “performers and fans alike, talk about being ‘country,’ they don’t mean they know or even care about the country and the life it sustains and regulates.” The way of life depicted by “country” is long gone, he argues, and what remains are empty symbols of bygone culture. “Are the hats, the boots, the pickup trucks, and the honky-tonking poses all that’s left of a disintegrating culture?”

“The “country” music establishment, including “country” radio and the “Country” Music Association, does after all seem to have decided that whatever “country” is, some of us aren’t.”

In any case, he himself does not seem to fully understand either why he was pigeonholed as “country musician” from Day One, and that lack of understanding is palpable. His breakthrough hit “I Walk The Line” (1956) may have been a so-called crossover hit, as it reached No 19 on the pop music charts, but it established Cash’s name by conquering the combined country charts: six weeks at No 1 on the U.S. Country Juke Box charts, one week at No 1 on the C&W Jockey charts, and No 2 on the C&W Best Seller charts. And when Cash looks around, up there, he sees hits like Elvis’ “Heartbreak Hotel” and “Hound Dog”, Carl Perkins’ “Blue Suede Shoes”, Fats Domino’s “Blueberry Hill” and Gene Vincent’s “Be-Bop-A-Lula”, all of which rank collegially alongside Hank Snow, Kitty Wells, George Jones and Porter Wagoner and all those other country greats… reviewing the Billboard Top Country & Western Records of 1956, it is indeed a bit puzzling according to which criteria a song is labelled as “country”. At least in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, “I Walk The Line” is permanently listed among “The 500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll”.

He himself tries to arrange a first audition with Sam Phillips as a gospel singer, but that does not convince the legendary Sun Records producer. No market for it, he thinks. Cash then tries as a C&W singer, ironically (“My next try didn’t work, either – that time I told him I was a country singer”), is allowed to audition and performs some Hank Snow songs, a Jimmie Rodgers song, a couple of Carter Family songs, but that doesn’t please either. Phillips wants to hear a song of his own, so Cash then just plays “Hey Porter” (“Though I didn’t think it was any good”). The producer immediately catches on: rockabilly! And with that, Cash has his first record deal: “Come back tomorrow with those guys you’ve been making the music with, and we’ll put that song down, he told me.”

The stamp “country” is inescapable, though. And Cash conforms to it. For his second album (The Fabulous Johnny Cash, 1958), he writes songs like “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town” and “I Still Miss Someone”, and records songs by country greats like Bob Nolan and Cindy Walker. But we can already see the love for folk too: the second track is Cash’s adaptation of the time-honoured “Frankie And Johnny”, in his case “Frankie’s Man, Johnny”. Which again scores crossover; #9 on the Billboard country chart, 57 on the Hot 100. And he confesses this love of folk wholeheartedly in his autobiography: “I was deeply into folk music in the early 1960s”. So he has Dylan in his sights early on:

“I took note of Bob Dylan as soon as the Bob Dylan album came out in early ’62 and listened almost constantly to The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan in ’63. I had a portable record player I’d take along on the road, and I’d put on Freewheelin’ backstage, then go out and do my show, then listen again as soon as I came off.”

With which he appears to be a true connoisseur; at most 2,500 copies of that first album were sold in 1962. So, by his own account, Johnny Cash did belong to that select club of buyers. More fascinating though, and more moving too, is the second part of his declaration of love, about his obsession with The Freewheelin’. His words are reminiscent of John Lennon’s in The Beatles Anthology (2000):

“In Paris in 1964 was the first time I ever heard Dylan at all. Paul got the record [The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan] from a French DJ. For three weeks in Paris we didn’t stop playing it. We all went potty about Dylan.”

And decades later, looking back, both McCartney and Lennon point to its influence. “Norwegian Wood”, “I’m A Loser”, “You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away”… “That’s me in my Dylan period again,” analyses Lennon in 1980, just before his death. Which Paul agrees, in 1984: “That was John doing a Dylan… heavily influenced by Bob. If you listen, he’s singing it like Bob.”

Cash – fortunately – does not sing like Dylan, but indeed: from 1962 onwards, when Cash says he is deeply into folk music, and so fond of listening to Dylan, we see a turnaround in repertoire choice. On Blood, Sweat And Tears (1963), which he recorded from June to August ’62, there are songs like “The Legend of John Henry’s Hammer” and “Casey Jones”, and in 1964 he records the successful Orange Blossom Special, with no fewer than three Dylan songs (“It Ain’t Me Babe”, “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” and “Mama, You’ve Been on My Mind”).

It makes it all the stranger that Cash makes such a mess of the lyrics of “Girl From The North Country” on Nashville Skyline.

If we take him at his word, that he listened almost constantly to The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan in ’63, before and after every gig on his portable record player, that alone is an impressive number of spins; in 1963, Cash did 61 concerts after the release of The Freewheelin’ (27 May 1963), so with that fact alone, we count 122 spins of “Girl From The North Country”. More than enough to have the lyrics indelibly imprinted on memory, one might say. But it actually goes wrong right from the start.

Alternately, the men apparently agreed. And presumably then the last verse, the repetition of the first verse, together. Dylan, with his new voice, does stay perfectly true-to-text, when he opens. However, when it’s Cash’s turn after that first verse, he does not sing the second verse, but the third. Sort of, anyway;

Dylan’s original Cash on Nashville Skyline

Please see for me if her hair hangs long See for me that her hair’s hanging down

If it rolls and flows all down her breast It curls and falls all down her breast [“frest”?]

Please see for me if her hair hangs long See for me that her hair’s hanging down

That’s the way I remember her best That’s the way I remember her best

… only the last line is unchanged. Which in itself is hardly a problem, of course. Dylan himself is the last person who thinks his lyrics are sacred; “They’re songs. They’re not written in stone. They’re on plastic” (SongTalk interview with Paul Zollo, 1991).

Dylan quickly switches gears and then sings the second verse himself, the verse Cash skipped. Ideally, The Man In Black would then do the fourth verse, but alas: he sets in the fifth, the last. Dylan is still alert and quick, and decides in a split second that this will be the last verse then, the two-part duet – Cash has only sung “If you’re…”, and Dylan is already joining in: “… travelin’, in the North Country fair”. The second line, Where the winds hit heavy on the borderline, then comes out smoothly, but by line three it goes wrong again. Dylan sings, as he should, Remember me to one who lives there, but his partner improvises Please say hello to the one who lives there. However, Cash has kept his ears open; when the men then sing the same verse one more time, he neatly follows the original lyrics.

Oh well, who cares. It is and remains an exciting combo of two giants showcasing their musical pleasure with a song that is so strong that it cannot be broken anyway. And who knows – perhaps Cash has just sown the first seed for “If You See Her, Say Hello” with his lyrics rehash here. Not an insignificant song either.

To be continued. Next up Girl From The North Country part 4 (final): À la fille, qui fut mon amour

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

Footnote:

Only girls from Minnesota have ‘frests’ …..

which makes most men go completely ape.

Listening to the lyrics of a song over and over and over again makes them “indelibly” imprinted on memory …

Jochen, are you sure???

Not in my case anyway it doesn’t!

But I think that’s the point Larry. As with all music and poetry of a certain complexity, what we take from the song depends very much on our life experiences, what we have read, what we have heard, what we feel… It’s different for each of us.