- I contain multitudes 1: Two Irish countries at odds

- I contain multitudes 2: To the buried that repose around us

- I contain multitudes part 3: The thrill of rhyming something that’s never been rhymed before

by Jochen Markhorst

IV Boogaloo dudes carry the news

A red Cadillac and a black moustache

Rings on my fingers that sparkle and flash

Tell me what’s next - what shall we do

Half my soul baby belongs to you

I rollick and I frolic with all the young dudes . . .

I contain multitudes

After the obvious tip of the hat to Warren Smith, the ensuing rhyme-find moustache-flash, and the whimsical associations it seems to trigger with his own “She Belongs To Me” and “Señor”, the poet affords himself a small fermata, a small pause to bridge to the varying refrain line. The insipid verse line Tell me what’s next – what shall we do leads to a distorted echo of “She Belongs To Me”, which apparently still reverberates in the creative part of the poet’s brain; Half my soul baby belongs to you and the facile, chewed-out rhyme do-you.

After the obvious tip of the hat to Warren Smith, the ensuing rhyme-find moustache-flash, and the whimsical associations it seems to trigger with his own “She Belongs To Me” and “Señor”, the poet affords himself a small fermata, a small pause to bridge to the varying refrain line. The insipid verse line Tell me what’s next – what shall we do leads to a distorted echo of “She Belongs To Me”, which apparently still reverberates in the creative part of the poet’s brain; Half my soul baby belongs to you and the facile, chewed-out rhyme do-you.

Still, slightly striking is the unusual “half my soul” – after all, in both poetry and song, the narrator always promises his whole soul, and at least as often even heart and soul to the object of desire. A diligent Arts & Culture reviewer finds, via Google Books no doubt, a single parallel in a rather obscure work, in a collection of 150 Jewish-mystical tales: “For in this generation, half of my soul belongs to you and the other half to another, whom you must seek out.” Definitely Dylanesque, yet still a little too obscure (it comes from Gabriel’s Palace: Jewish Mystical Tales, compiled and edited by university professor Howard Schwartz in 1994) to be promoted to purveyor of a Dylan song lyric.

In the canon, we really only know this particular word combination from Shakespeare, from one of his most bloody revenge tragedies, the youthful error Titus Andronicus. The tragedy in which, right from the very first scene of the first act, a son of an enemy king is sacrificed by chopping off all his limbs, after which, up until the last scene of the last act, the blood continues to spatter, heads roll, entrails fly around and skulls are cleaved. Fitting, on reflection, with Dylan’s preoccupation with gory violence since Tempest (2012) and the not yet fading fascination with it here on Rough And Rowdy Ways. This unusual word combination “half my soul” we can hear in the very first minutes of that über-bloody Shakespearean tragedy:

TITUS

Speak thou no more, if all the rest will speed.

MARCUS

Renowned Titus, more than half my soul—

LUCIUS

Dear father, soul and substance of us all—

Far-fetched, but not entirely inconceivable; in the 2015 AARP interview, Dylan reveals a hobby that entertains him during his many gigs in faraway foreign lands too;

“I like to see Shakespeare plays, so I’ll go — I mean, even if it’s in a different language. I don’t care, I just like Shakespeare, you know. I’ve seen Othello and Hamlet and Merchant of Venice over the years, and some versions are better than others. ”

… although Titus Andronicus is – rightly – not performed too often.

More musical and funnier then is the closing line, the varying refrain line – in this stanza I rollick and I frolic with all the young dudes… I contain multitudes. In the 1980s, Dylan once built an entire lyric on frenzied rhymes on the name “Angelina” (concertina, hyena, subpoena), and by now it’s becoming clear that Dylan still finds it a fun finger exercise in 2020. The margin of the first draft of “I Contain Multitudes” is no doubt filled with a good dozen candidates like canned foods, quaaludes and hungry prudes, or something like that anyway, and in the final draft Dylan then chooses blood feuds, painting nudes and now, then, all the young dudes.

It seems obvious that “nice rhyme” was the only argument for using the title of Mott The Hoople’s 1972 world hit. After all, there are not too many tangents between the glam rockers or Bowie’s “All The Young Dudes”, and Dylan’s oeuvre or even just Dylan’s interests. However, there’s still a bit more to it. The song had a generation-splitting impact at the time, at least in the England of the early 1970s, when androgynous appearances like Bowie and The Sweet and Mott The Hoople were actively reviled in opinion-forming gutter magazines like the Daily Mirror. Morrissey illustrates the song’s diverging power with deadpan humour in his successful Autobiography (2013):

“In 1972 I had played All the young dudes by Mott the Hoople to my father, and as it spun innocently before us on orange CBS, he stands to leave. ‘Ooh no, I’m not having that,’ were his words as he vanished in disgust. What exactly he wasn’t having I still do not know. He walks around the house singing Four in the morning by Faron Young, or Scarlet ribbons by somebody else.”

… so the song already should score sympathy points with a cross-thinker like Dylan, of course. Most remarkable, however, is journalist/writer Robert Christgau’s testimony in the Village Voice, 4 August 1975. Christgau was at that famous impromptu Dylan performance at The Other End in Greenwich Village in August ’75, when Dylan climbs onstage at around one o’clock at night and performs still-unknown songs like “Joey” and “Isis” in front of a select audience of musicians, a few journalists and other fortunate lucky devils. Among the musicians present are artists like Patti Smith, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Mick Ronson. And…

“Also present was that old Dylan imitator, Ian Hunter, who was having his head blown off — not only had Dylan identified him as a member of Mott the Hoople (which he’s not any more, as if Hunter could care) but he’d known all the tracks on Hunter’s (or was it Mott’s) first album. Unbelievable.”

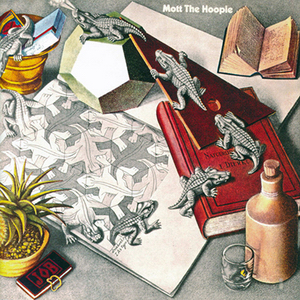

Christgau’s “unbelievable” communicates an understandable surprise; Mott’s unnamed 1969 first album was not very successful (two weeks in the Billboard 200, highest listing 185). But perhaps Dylan was alerted to it because of the album’s Dylanesque nature. No coincidence: legendary producer (and names giver of both Mott The Hoople and Procol Harum) Guy Stevens deliberately wanted to make a Dylan-meets-Rolling Stones album – and succeeds completely. And it’s the album with the cover on which Escher’s lizards rollick and frolic, of course.

In the twenty-first century, the band is still on Dylan’s radar; as a DJ on his Theme Time Radio Hour, he plays the highly infectious rocker “All The Way To Memphis” (episode 31, Memphis, 29 November 2006), introducing it with unmistakable joyful anticipation;

“Hoople is an English term for a person on their knees, repenting of their sins. Here’s Mott The Hoople. This song was written by their lead singer Ian Hunter, and a story about being on the road, realising they left their guitars behind. They put this embarrassing song to music, and put it out on their album called Mott. Here’s Mott The Hoople, going All The Way To Memphis.”

… wherein we hear halfway through:

Yeah it's a mighty long way down rock 'n' roll From the Liverpool docks to the Hollywood bowl 'n you climb up the mountains 'n you fall down the holes All the way from Memphis

… from which Dylan gratefully copies From the Liverpool docks to the red light Hamburg streets, a few years later, for his Lennon ode “Roll On John”.

“Can you still listen to music passively,” Jeff Slate asks in that Wall Street Journal interview in December 2022, “or are you always assessing what’s special about a song and looking for potential inspiration?”

“That’s exactly what I do,” Dylan says. “I listen for fragments, riffs, chords, even lyrics. Anything that sounds promising.”

To be continued. Next up I Contain Multitudes part 5: All the people on earth… all you

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

Nevertheless, it’s obvious Whitman-influenced Dylan impacts Bowie’s lyrics more rather than other way around.

Likewise the Hopple

Hoople, as said, be clearly influenced by Dylan word style.

Also, just because a Jewish source for ” half my soul” is “obscure” it’s supposed not to be a source, but ….why not?. . who knows that is not or is the case – without backup?

Dylan might be said by someone to like ‘glam’ music, but l have my doubts given his works at large. Ie, instead could be a Dylanesque “put on”… though I have no particular ‘hard’ proof to backup the claim.

“Glam” attracted the bisexual and ‘gay’ crowd with Bowie lines like ‘all the young dudes”; Whitman’s “young men and all so friendly”( Song of Myself), places him as a glam poet ahead of his time.

Bob Dylan hung around with Beat poet Ginsberg, but for the most part sticks to folk and rock music and lyrics about relationships between guys and gals.