- I contain Multitudes 1: Two Irish countries at odds

- I contain Multitudes 2: To the buried that repose around us

- I contain Multitudes 3: The thrill of rhyming something that’s never been rhymed before

- I contain Multitudes 4: Boogaloo dudes carry the news

- I contain Multitudes 5: All the people on earth… all you

- I contain Multitudes 6: All things lost on earth are treasured there

- I contain Multitudes 7: Allen’s outer ear

by Jochen Markhorst

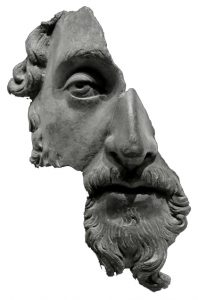

VIII Time is a river, a violent torrent of events

I sing the songs of experience like William Blake I have no apologies to make Everything’s flowin’ all at the same time I live on the boulevard of crime I drive fast cars and I eat fast foods . . . I contain multitudes

Dylan is interviewed twice for Rolling Stone in a relatively short space of time; in 2009 by Mikael Gilmore, in 2012 by Douglas Brinkley. And both times the name Marcus Aurelius comes up, the last of the Five Good Emperors, who became immortal mainly because of his Meditations, the self-exploratory and philosophical notes that the wise emperor jotted down between 161 and 180 just for himself. Apparently, he is also on a pedestal with Dylan; in 2009, Dylan cites him as an example of the Antique writers he keeps re-reading, writers like Plutarch, Cicero and Tacitus, because “I like the morality thing”. And then Marcus Aurelius is your man alright. Three years later, in 2012, Dylan has found even more depth, saying:

Dylan is interviewed twice for Rolling Stone in a relatively short space of time; in 2009 by Mikael Gilmore, in 2012 by Douglas Brinkley. And both times the name Marcus Aurelius comes up, the last of the Five Good Emperors, who became immortal mainly because of his Meditations, the self-exploratory and philosophical notes that the wise emperor jotted down between 161 and 180 just for himself. Apparently, he is also on a pedestal with Dylan; in 2009, Dylan cites him as an example of the Antique writers he keeps re-reading, writers like Plutarch, Cicero and Tacitus, because “I like the morality thing”. And then Marcus Aurelius is your man alright. Three years later, in 2012, Dylan has found even more depth, saying:

“There’s truth in all books. In some kind of way. Confucius, Sun Tzu, Marcus Aurelius, the Koran, the Torah, the New Testament, the Buddhist sutras, the Bhagavad-Gita, the Egyptian Book of the Dead, and many thousands more.”

Dylan articulates the insight that most of us do reach, sooner or later: that the Great Truths of all religions, cultures and times overlap. We hear an expression of that insight here, in the key line of the fourth verse, also one of Dylan’s Eternal Themes: Everything’s flowin’ all at the same time. A Great Truth that we encounter often enough among Buddhists anyway, and is also expressed quite literally that way in the narrative that, at least in the Western world, is the most popular and widely read Buddha story, in Hermann Hesse’s Siddharta (1922):

“The river is everywhere at once, at its source and at its mouth, at the waterfall, at the ferry, at the rapids, in the sea, in the mountains, everywhere at once, and only the present exists for it, and not the shadow of the future.”

… a wisdom with which Dylan’s song already opens (“Today and tomorrow and yesterday too”), which is a common thread throughout the album Rough And Rowdy Ways, and throughout all of Dylan’s oeuvre, of course. And in some kind of way Dylan finds that insight in all those books he lists there, and in many thousands more. In the Torah as in the Bhagavad-Gita – a title that stands out rather undylanesque in that list. But indeed, Dylan finds confirmation there too. In Chapter 10, Vibhuti Yoga, “The Yoga of Divine Splendour”, in Verse 33, for example:

“Of letters I am the letter A. Amongst compound words I am the dual. I alone am the eternal flow of the time factor and I am the Creator, who gazes in all directions.”

… spoken by the being who in a more literal sense than Whitman’s Myself contains multitudes, by Krishna, the Creator who gazes in all directions.

And refreshed it is, at least so it seems, by the only author he lists as a signpost in both 2009 and 2012, by Marcus Aurelius. No doubt Dylan had several aha-moments when reading Meditations, but a checkmark in the margin he will have made at Meditation 43, “Time is a river, a violent torrent of events coming into being; and as soon as it has appeared, each one is swept off and disappears, and another follows, which is swept away in its turn”, and if not, at Meditation 37:

“If you’ve seen the present, then you’ve seen everything — as it’s been since the beginning, as it will be forever. The same substance, the same form. All of it.”

But surely the direct trigger for this one verse will again be the same as the trigger for the whole song at all: Walt Whitman’s “Song Of Myself”. Most clearly, of course, in Whitman’s identical denial of a linear passage of time, in Section 23: “Here or henceforward it is all the same to me, I accept Time absolutely”. Which in “Song Of Myself”, as in Dylan’s oeuvre, is a refrain, by the way. “A few quadrillions of eras,” Whitman composes a little further on, “they are but parts, any thing is but a part”, for example, and six lines before the I contain multitudes quote in Section 51:

The past and present wilt—I have fill’d them, emptied them, And proceed to fill my next fold of the future.

… and what has rarely been so beautifully visualised as by Christopher Nolan in Interstellar, in that psychedelic, poignant tesseract scene towards the end of the film. In which the robot Tars has to explain to the bewildered Cooper that he is indeed seeing what he is seeing: everything’s flowing all at the same time.

TARS

(over radio)

I don’t know, but they constructed this three-dimensional space inside their five-dimensional reality to allow you to understand it …

COOPER

It isn’t working -!

TARS

(over radio)

Yes, it is. You’ve seen that time is represented here as a physical dimension – you even worked out that you can exert a force across spacetime –

COOPER

(realizing)

Gravity. To send a message …

Cooper looks around the infinite tunnel, infinite Coopers.

COOPER

Gravity crosses the dimensions – including time –

Which is clever thinking on Cooper’s part. “Poetry” would have been a nicer dimension-crossing option, of course, but gravity might be a bit more practical in this case to get to the film’s denouement.

Anyway: the Bhagavad Gita from the third century BC (supposedly), Marcus Aurelius from the second century AD, Whitman in the nineteenth and Hesse in the twentieth and Interstellar in the twenty-first… reasoning circularly, with that one phrase Everything’s flowin’ all at the same time Dylan demonstrates how at least poetry has the power to transcend Time.

————–

To be continued. Next up I Contain Multitudes part 9: None of this has to connect

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

the river is a lead argument of rough and rowdy ways, the songs on tour among others..whatching the river flow, only a river ecc…

i believe that is a good root to follow.