Goodbye Jimmy Reed (2020) part 2

by Jochen Markhorst

II All songs lead back t’ the sea

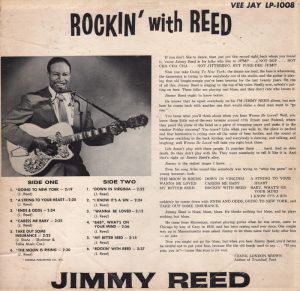

Over the years, Jimmy Reed pops up occasionally in Dylan’s working life. He plays “Big Boss Man” with Eric Clapton at the Crossroads Benefit Concert in June 1999 in New York City, and again with Grateful Dead in 2003; he tries “Baby, What Do You Want Me To Do?” during a rehearsal for Farm Aid (1985); as a DJ, he plays two songs by Jimmy Reed (“Going To New York” and again “Big Boss Man”); in interviews and in Chronicles, Dylan keeps mentioning the name as an example of an admired artist, and in 2022, i.e. after his tribute “Goodbye Jimmy Reed”, Dylan goes in his Philosophy Of Modern Song into more detail regarding his admiration for “Jimmy Reed, the essence of electric simplicity”. “Big Boss Man” gets its own chapter (Chapter 53) and in it Dylan makes it unequivocally clear what touches him so much in Reed’s recordings for Vee-Jay Records:

Over the years, Jimmy Reed pops up occasionally in Dylan’s working life. He plays “Big Boss Man” with Eric Clapton at the Crossroads Benefit Concert in June 1999 in New York City, and again with Grateful Dead in 2003; he tries “Baby, What Do You Want Me To Do?” during a rehearsal for Farm Aid (1985); as a DJ, he plays two songs by Jimmy Reed (“Going To New York” and again “Big Boss Man”); in interviews and in Chronicles, Dylan keeps mentioning the name as an example of an admired artist, and in 2022, i.e. after his tribute “Goodbye Jimmy Reed”, Dylan goes in his Philosophy Of Modern Song into more detail regarding his admiration for “Jimmy Reed, the essence of electric simplicity”. “Big Boss Man” gets its own chapter (Chapter 53) and in it Dylan makes it unequivocally clear what touches him so much in Reed’s recordings for Vee-Jay Records:

“Jimmy Reed is about space. About air being moved around the room. You feel like you can see the light hitting the dust as it swirls under the sway of music.”

“It never sounds crowded,” he adds. Exactly the aspect he himself, very consciously, strives for. In the 2008 Uncut interview, session musician Jim Dickinson (keyboardist on Time Out Of Mind) reveals:

“One thing that really struck me during those sessions, Dylan, he was standing singing four feet from the microphone, with no earphones on. He was listening to the sound in the room.”

In which he fully succeeds, as Henry Rollins argues. Rollins, a soul mate of Dylan’s and a source from which Dylan gratefully and frequently draws at the time of Time Out Of Mind (1997), as we know thanks to the digging of Dylan researcher Scott Warmuth, laments the general sound quality that is predominant from the 1990s onwards, from the time Pro Tools emerged. Everything sounds so “contained”, Rollins complains to the DVD Talk interviewer (February 2004):

“I miss the space, I miss the sound of a guitar in a room where you can hear the air around it. Who makes records like that still? Tom Waits does, Bob Dylan does.”

… almost literally the vocabulary Dylan uses to express the magic of Jimmy Reed’s sound. And what Dylan also immediately hears in Boz Scaggs’ recording of “Down In Virginia”, no doubt: space, the air around it.

The crystal-clear, splashing intro riff by Charlie Sexton, Jim Keltner’s claps on the drums resounding as if they were in the stairwell, a slight reverberation on Jack “Applejack” Walroth’s piercing harmonica, succeeding excellently in imitating Jimmy Reed’s flares and fireworks, the warmth of the bass and the intimacy of Boz’s voice that sounds as if he’s standing next to you in the kitchen… it’s quite understandable that Dylan falls head over heels for this recording. And it is probably no coincidence either that this is the only song on Rough And Rowdy Ways for which Dylan finally pulls his harmonica out of his inside pocket again.

A few days after his gig for Scaggs in March 2018, Charlie Sexton then reports to Dylan for rehearsals for the upcoming Europe tour, which kicks off 22 March in Lisbon. It seems obvious that over a coffee break Charlie would tell Dylan what he has been up to recently, and that Dylan would be eager to hear those recordings. Charlie knows that his employer is a Jimmy Reed fan. And that subsequently, upon hearing the Scaggs recording, Dylan’s “Bob Nolan mechanism” is activated;

“What happens is, I’ll take a song I know and simply start playing it in my head. That’s the way I meditate. […] I’ll be playing Bob Nolan’s Tumbling Tumbleweeds, for instance, in my head constantly — while I’m driving a car or talking to a person or sitting around or whatever. People will think they are talking to me and I’m talking back, but I’m not. I’m listening to the song in my head. At a certain point, some of the words will change and I’ll start writing a song.”

(Robert Hilburn interview, Los Angeles Times 2003)

Of which we know plenty of examples, of course. “Sugar Baby”, “Girl From The North Country”, “Floater”, “Masters Of War”, “Things Have Changed”… Dylan has been using the “Bob Nolan method” for sixty years now, listening to “The Lonesome Road”, “Scarborough Fair”, “Snuggled On Your Shoulder”, “Nottamun Town”, “Observations Of A Crow” in his head, and at a certain point, some of the words will change and I’ll start writing a song. Which has also been sparking the not very fruitful plagiarism-or-inspiration debates for sixty years now, but Dylan himself, in the liner notes of The Times They Are A-Changin’ sixty years ago, was pretty clear about it, especially in the eighth of the “11 Outlined Epitaphs”:

(influences? hundreds thousands perhaps millions for all songs lead back t’ the sea an’ at one time, there was no singin’ tongue t’ imitate it) t’ make new sounds out of old sounds an’ new words out of old words

… and making “new sounds out of old sounds” Dylan has continued to do. “Good artists borrow, great artists steal” is usually attributed to Picasso, and just as often to T.S. Eliot (who indeed wrote “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal” in his essay Philip Massinger, 1920). And to Steve Jobs, Stravinsky and Faulkner and dozens more – all of whom undoubtedly have said something along these lines at one time or another. And Dylan’s version, which he writes down in the opening of this same eighth Outlined Epitaph, shamelessly proclaims the same thing, basically:

Yes, I am a thief of thoughts not, I pray, a stealer of souls I have built an’ rebuilt upon what is waitin’

“A word, a tune, a story, a line,” philosophises the young song poet, “keys in the wind t’ unlock my mind.”

Over half a century later, Charlie Sexton plays the tape with the “Down In Virginia” cover he has just recorded with Boz Scaggs. I went down in Virginia, honey, where the green grass grows, repeats the tape in Dylan’s head, as his right hand searches for a pencil. Soon, he knows, some of the words will change.

To be continued. Next up Goodbye Jimmy Reed part 3: An amazing ability

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

Dylan’s influenced for sure by the ‘uncontained’ music and words of Reed, Scaggs, and others but how much Dylan, “the thief”, owes to Henry Rollins, rather than the other way around, is debatable.

Bob Nolan lived in Hatfield Point New Brunswick for a bit of time when a youngster

Sings Dylan:

When you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose (Like A Rolling Stone)

Darkened up, inversed, by Rollins to:

Now if you think you lost it all, you’re wrong

You can always lose a little more (Great Outdoors)

Back at you by Dylan:

When you think that you lost everything

You can always lose a little more (Trying To Get To Heaven)

It takes a thief, maybe with the help of an an Indian chief, to catch a thief.