High Water (for Charley Patton) (2001) part 2

by Jochen Markhorst

II A service with a real preacher

High water risin’, the shacks are slidin’ down Folks lose their possessions—folks are leaving town Bertha Mason shook it—broke it Then she hung it on a wall Says, “You’re dancin’ with whom they tell you to Or you don’t dance at all.” It’s tough out there High water everywhere

John Fogerty confesses that he got to know Charley Patton’s work very late – had never even heard of him until 1990. Then, in 1990, he has a “Mississippi itch”, an irrational, nagging need to visit the birthplace of the blues, and eventually gives in to it. He makes six weekly trips across Mississippi, he says, as a kind of pilgrimage. Fogerty goes to the plantation where Muddy Waters grew up, looks for the graves of men like Robert Johnson, and he visits Dockery Plantation, the birthplace of the Delta Blues, where Howlin’ Wolf and Robert Johnson lived… and where Charley Patton came from, as he understands from a book he buys there (he doesn’t mention the title, but Robert Palmers Deep Blues is an educated guess). When Fogerty is then introduced to Patton’s music, it’s an instant hit:

John Fogerty confesses that he got to know Charley Patton’s work very late – had never even heard of him until 1990. Then, in 1990, he has a “Mississippi itch”, an irrational, nagging need to visit the birthplace of the blues, and eventually gives in to it. He makes six weekly trips across Mississippi, he says, as a kind of pilgrimage. Fogerty goes to the plantation where Muddy Waters grew up, looks for the graves of men like Robert Johnson, and he visits Dockery Plantation, the birthplace of the Delta Blues, where Howlin’ Wolf and Robert Johnson lived… and where Charley Patton came from, as he understands from a book he buys there (he doesn’t mention the title, but Robert Palmers Deep Blues is an educated guess). When Fogerty is then introduced to Patton’s music, it’s an instant hit:

“When he started to sing, the hair on the back of my neck stood up: “Oh my God, he sounds like that?” It was like hearing Moses. […] I thought, This is where it all starts.”

(John Fogerty, Fortunate Son, 2015)

He then wants to visit Charley Patton’s grave at Holly Ridge, which eventually turns out to be unmarked. Only thanks to a confident, retired cemetery caretaker to whom the exact location was pointed as a child does he find the spot. Fogerty decides to fund a headstone, contacts the family and eventually even a service is organised.

“They had an official ceremony, unveiling the headstone on July 20, 1991. They had a service, with a real preacher. It was moving. One of Patton’s relatives was there. I had a little guitar slide in my pocket, and so, hoping that a little Patton mojo might rub off, I talked her into holding it for a few seconds. It was hotter than blazes that day. I sat next to Pops Staples, who was wearing a breezy, all-white linen suit.”

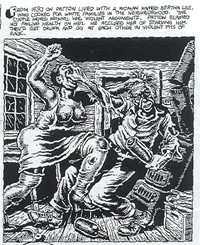

The source that presumably introduces Fogerty to Patton, Robert Palmer’s beautiful book Deep Blues (1981), is the same as the one used by graphic artist Robert Crumb for his breathtaking masterpiece Draws The Blues (1995), in which the chapter on Charley Patton, the shiftless no-good rambler who lived off women, is the highlight. Twelve pages of graphic miniatures in black and white that essentially depict Palmer’s story about Patton, with, as in Palmer’s book, a focus on the dramatic climax of Patton’s life, the four final years full of hate and love with Bertha Lee, who also sings along on his last recordings (1934, “Troubled ‘Bout My Mother” and “Oh Death”, fittingly enough).

So it does seem obvious that Bertha Lee triggered the appearance of the name “Bertha” in the second verse of Dylan’s “High Water”. The other, more poetic, source could be Johnny Cash. In the manuscript of “High Water”, “Bertha Mason” only appears on second thought. The first rough version of the second verse is:

High water Risin’ – shacks are sliding around High water Risin’ – things are sinking down Riding on Train 45, pawned my watch and chain Got pulled in Vicksburg but they weren’t letting me off the train Things came to a full stop there

… no “Bertha”, but rather “Vicksburg”. The historic city name imposes itself on Dylan through Patton’s “High Water Everywhere”, of course (Well, I’m goin’ to Vicksburg for that high of mine), but in the meantime also leads the associations to

I got a gal in Vicksburg Bertha is her name Wish I's tied to Bertha Instead of this ball and chain

… to “I’m Going To Memphis” from Cash’s 1960 “train album” Ride This Train.

Dylan’s stream of consciousness seems to be churning, meanwhile. In Patton’s song, Charley gets on the train to flee the Great Flood. Rosedale, Blytheville, Leland. Greenville… but the high water follows him everywhere. So Patton’s train journey apparently awakens the archetypal song “Train 45” in Dylan’s mind (the seed that spawned “Reuben’s Train”, “900 Miles” and “500 Miles”), igniting in turn his own derivative of that archetypal song, “I Was Young When I Left Home”, which may be why it is added as a bonus to the Limited Edition of “Love And Theft”;

When I pay the debt I owe To the commissary store, I will pawn my watch and chain and go home. Oh home, Lord Lord Lord, I will pawn my watch and chain and go home

“Pawn my watch and chain”, which the young Dylan didn’t have from himself either at the time, in 1961, obviously. From Dinah Washington’s superior “Nobody Knows The Way I Feel This Morning” perhaps (I pawned my ring, gold watch and chain), but more obvious is Woody Guthrie’s version of “Nine Hundred Miles” from 1944:

I will pawn you my wagon, I will pawn you my team, I will pawn you my watch and my chain; And if this train runs me right I'll see my woman Saturday night, I’m tired of livin’ this a-way And I hate to hear that lonesome whistle blow

Anyway, back to “High Water”. Of the first draft of this second verse, only the first line eventually remains; the follow-up lines, with that flood of references, associations and allusions, are again deleted. In the margin of the manuscript, we already see “Bertha Mason” popping up, each time in combination both with “Joe Turner” and – still – with “Train 45” (twice, and both times Train 45 drives “into the next time zone”). Neither the train nor the time zone survive the final editing, but “Bertha Mason” remains. In the final version explicitly detached from Joe Turner, and moved to Charley Patton; Bertha Mason shook it-broke it / Then she hung it on a wall is, after all, an unconcealed reference to

Just shake it, you can break it, you can hang it on the wall Out the window, catch it 'fore it roll You can shake it, you can break it, you can hang it on the wall Out the window, catch it 'fore it falls My jelly, my roll, sweet mama, don't let it fall

… to Patton’s 1929 “Shake It And Break It”. So it almost seems, in that sketching phase of “High Water”, that Dylan simply mistook Bertha Lee’s name – or, for reasons of rhythm, wanted a surname of two syllables (although that seems more unlikely, given Dylan’s unrivalled mastery of phrasing). A fruitful mistake, in that case; many Dylan-exegetes go looking and find as a prime candidate one “Bertha Mason” in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, where she is a colourful secondary character – a crazy Creole woman, “violently insane”, who spends most of the book locked in the attic. The find leads to entertaining reflections from analysts, but it is still very unlikely that Dylan’s – admittedly highly associative – mind led him to that gothic Bildungsroman from the nineteenth century. No, it is still more plausible that during that sketching phase, a country music station was playing soft in the background. Mark Knopfler’s hit “Sailing To Philadelphia” then, combining Charley Patton and Bertha Mason;

He calls me Charlie Mason A stargazer am I

Well, equally implausible anyway.

To be continued. Next up High Water (For Charley Patton) part 3: You got a fast car

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B