Previously in the series

- The Rough and Rowdy Way Tour: 2021.

- The Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour: Most likely you go your way and I’ll go mine

- I contain multitudes

False Prophet starts at 14 minutes 45 seconds. The music is based on Billy “The Kid” Emerson’s 1954 single “If Lovin’ Is Believin'”.

You have been so deceiving tell me when are you leaving When you go will you set me free? I Haven't been my best but you made such a mess Of the plans that were going to be But if love it is believing Tell me why don't you believe in me

I gave you everything that money could buy I haven't been my best but heaven knows I thought I tried The things that I said baby you thought you'd never see You said that you loved me that's the way it's going to be But is love it is believing Tell me why dont you believe in me

The Three Milkshakes version of the song is a direct copy of the original. This was recorded in 1992.

Bob’s lyrics however take us to a totally different place.

Another day that don't endAnother ship goin' outAnother day of anger, bitterness, and doubtBut I know how it happened, I saw it beginI opened my heart to the world and the world came in Hello Mary LouHello Miss PearlMy fleet-footed guides from the underworldNo stars in the sky shine brighter than youYou girls mean business, and I do too

So what is the false prophet of whom Bob Dylan sings while claiming it isn’t him? The most obvious answer is that as Dylan openly takes a song from 1954 and changes the words, he’s not only not a false prophet he is not a prophet at all – but a person recognising that enjoying music from the past and playing with it by adding one’s own lyrics, is a perfect legitimate and enjoyable experience.

So what is the false prophet of whom Bob Dylan sings while claiming it isn’t him? The most obvious answer is that as Dylan openly takes a song from 1954 and changes the words, he’s not only not a false prophet he is not a prophet at all – but a person recognising that enjoying music from the past and playing with it by adding one’s own lyrics, is a perfect legitimate and enjoyable experience.

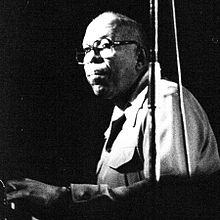

The picture here is Billy Emerson toward the end of his life – he died in 2023, so maybe he and Bob met and Mr Emerson heard Bob’s piece.

We might in passing feel sorrow for the injustice done to Billy Emerson who seemingly made not a penny from writing and recording the song, but on the other hand maybe some people have now taken the song and gone back to find other Billy Emerson compositions and recordings. Not least because musically Bob’s song is an absolute copy of the original.

And maybe all this is a link back to a concert in 1980 in which Dylan said, “I used to say, ‘No I’m not a prophet’. They’d say, ‘Yes you are, you’re a prophet’. I said, ‘No it’s not me’. They used to say, ‘You sure are a prophet’. They used to convince me I was a prophet.” Billy Emerson was a musical prophet however. But few recognised him as such.

Another possible starting point for the song was the fact that Cardinal Ratzinger who became Pope Benedict XVI spoke against Dylan playing at a Catholic Youth concert. Later he wrote that he had “doubts to this day whether it was right to let this kind of so-called prophet take the stage” in front of the Pope.

There’s also been a fair amount of work done in relating the lyrics to the last days of the 500 year old Roman Republic as Julius Caesar stepped up to end its life and create the Roman Empire. Maybe – maybe not.

And of course we have a few quotes from the Egyptian Book of the Dead, such as “Another day of anger, bitterness and doubt” and “I opened my heart to the world and the world came in.” And why not? If the music is completely copied from an old blues song, and perhaps is created in honour of one of the great original but unrecognised blues artists, why not have the lyrics taken from the Book of the Dead?

In the end what we have is a copy and a pastiche, which turns into a great piece of music that really demands our attention and pulls us forward, without perhaps our ever knowing what all this means and why it is such fun to listen to.

And if that is the point, this performance works 100%. It is powerful, it certainly pulls me into its orbit, and actually in the end I don’t really care too much what the lyrics mean and where it comes from; I just enjoy the sound.

But more than that, it was this performance that really brought home to me the line “I opened my heart to the world and the world came in.” Suddenly I got that as a reference to all the love and heartache that one can enjoy and suffer in the course of life and it became one of my favourite lines.

So for me, that’s all it has to mean, and in that regard, this live performance gives me quite a bit more than the album release does.

I don’t really care too much what the the lyrics mean ….

Seems odd to dismiss Dylan’s lyrics just because the accompanying music can be heard by the analyst elsewhere by someone else

Why bother with Dylan ‘False Prophet’ at all if in the end it’s only the music that really matters?

False Prophet

‘Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men?’

With characteristically fastidious self-deprecation, TS Eliot’s Prufrock, in a poem alluded to – almost

quoted from – by Dylan in ‘Desolation Row’, announces:

I am no prophet – and here’s no great matter

Dylan, by contrast, insists over and over, with an unPrufrockian defiance reaffirmed by a driving blues bea

I ain’t no false prophetThe insistence draws attention to the telling epithet, ‘false’, as much as to the key word ‘prophet’, and there’s a typical ambivalence here, something that underscores the song and its possible meanings: by declaring that he’s not a ‘false prophet’ is the speaker here denying prophetic qualities or affirming that he’s not ‘false’ – ie he is prophet of sorts, and one we can trust, or should pay heed to? I’m very much inclined to the latter.

It’s a cliché to say that we live in an age of ‘fake news’, but like so many clichés (it’s how they become them) it contains a truth: we’re confronted and affronted everywhere by fakery and falsehood, by lying politicians and their sycophantic media cronies inventing ‘facts’. By insisting on not being a false prophet the voice of the poem is setting itself apart from and in opposition to fakery.

The claim to be a prophet is a large one, but it calls to mind William Blake (whose ‘Songs of Experience’ are referenced in ‘I Contain Multitudes’) and his vision of the poet as seer, possessing a wisdom, an ability to see what others are blind to, a prophet who speaks truth to the present day from the perspective of an outsider, even a voice in the wilderness, one, perhaps, who goes ‘where only the lonely can go’:

Hear the voice of the Bard!

Who Present, Past, & Future sees

Blake claims that Milton, for example, was ‘a true poet’ who regarded that kind of Energy ‘call’d Evil’ as the ‘only life’. Blake considers Energy to be opposed to Reason, the force which, he believes, restrains desire. He exalts the life of the passions over that of Reason and the true poet/seer/prophet should exalt passionate life and deny imprisoning restraint, the ‘mind-forg’d manacles’ (in ‘London’) that chain us down. Comparably, Dylan’s prophet declares:

I’m the enemy of the unlived meaningless life

(Intriguingly, too, where Blake is the enemy of reason (mocked punningly as a god, Urizen) Dylan’s prophet – or seer – declares himself ‘the enemy of treason’.)

This elevation of Energy led Blake to believe that Milton in Paradise Lost was unconsciously on Satan’s side:

The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devils party without knowing it.

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790)

Dylan’s ‘enemy of the unlived meaningless life’ can appear to be something like an embodiment of that Blakean Energy and Passion as he declares with a kind of snarling swagger:

I’m first among equals – second to none

I’m last of the best – you can bury the rest

Don’t care what I drink – don’t care what I eat

I climbed a mountain of swords on my bare feet

The extravagant boasting culminates in a reference to Wumen Huikai a Chinese Chán (in Japanese: Zen) master during China‘s Song period, apparently famed for the 48-koan collection The Gateless Barrier, including this:

You must carry the iron with no hole.

No trivial matter, this curse passes to descendants.

If you want to support the gate and sustain the house

You must climb a mountain of swords with bare feet.

The commands are knowingly absurd, the feats demanded hyperbolic. That’s their point. Dylan’s Prophet, though, will have us believe that he’s achieved at least one of them.

In fact, as elsewhere on this multitudinous album – ‘Key West’, for example, is a rich, mesmerising dramatic monologue – we find ourselves wondering about the voice we’re hearing, who we’re hearing, as Dylan again appears to be adopting a persona – and part of the challenge of engaging fully with the song’s meaning(s) is coming to terms with that persona, or in this song’s case, personae? After all, ‘I is another’: ‘I and I’.

The image accompanying the early-released single offers a cryptic clue. It’s a loaded pastiche of the cover image for The Shadow #96, featuring the stories ‘Death About Town’ and ‘North Woods Mystery’. (Death About Town, we also read, ‘stalks rich and poor alike’.) The skeletal figure is The Shadow himself:

Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? Every fan of old-time radio, the fruit of a “golden age” on the American airwaves which lasted from the 1920s until television took hold, can tell you the answer: The Shadow knows.

http://www.openculture.com/2016/04/orson-welles-stars-in-the-shadow.html

The Shadow knows the evil lurking in men’s hearts and here he (or a version of him) carries a syringe with an intention we can only guess at (poison or a vaccine?) while behind him the silhouette of a hanged man has a Trumplike forelock. Dylan’s speaker stalks the land, and like The Shadow, ‘I just know what I know’.

Then again, ‘It may be the Devil, it may be the Lord…’ The persona, the voice, swings from boasts and vengeful threats, like an Old Testament Jehovah (Blake’s ‘Nobodaddy’) ‘here to bring vengeance’, to inveigling seducer as oily as Satan – who can also, of course, come disguised ‘as a Man of Peace’ – tempting Eve in the Garden of Eden:

What are you lookin’ at – there’s nothing to see

Just a cool breeze encircling me

Let’s walk in the garden – so far and so wide

We can sit in the shade by the fountain side…

Shade cast by the Tree of Knowledge, Blake’s ‘Poison Tree’?

.

Tracking the voice as it addresses us through the verses, we begin with a world-weary, even cynical note of resignation:

Another day without end – another ship going out

Another day of anger – bitterness and doubt

Shadows are falling but it’s a day without end, dragging towards eternity, ships ‘going out’, their journeys unnamed, unremarked upon. Days wearily repeat themselves, full of tellingly unspecified ‘anger’ and coloured by ‘bitterness and doubt’. The near-hopelessness, though, shifts to something closer to a worldly knowingness, the voice of a prophet looking back, one who’s seen it all, who saw, too, what was coming – ‘I know how it happened – I saw it begin’ – but one who also suffered, martyr-like, in his truth-telling and in his searching, we later hear, for ‘the holy grail’:

I opened my heart to the world and the world came in

If you ‘open your heart’ to someone, you tell them truths, your real thoughts and feelings, because you trust them – but in doing that you’re at the same time rendering yourself vulnerable, opening yourself to another’s exploitation if that trusted person turns out to be anything but trustworthy: you can be taken advantage of, something that’s implied here by the embittered follow-on, sung with a tired sense of seen-it-all beforeness: ‘and the world came in’. You ‘open your heart’ to or confide in usually one person, not to ‘the world’, but the speaker’s naïve mistake was perhaps to have assumed that his audience would listen and respond with generosity of spirit rather than seizing an advantage, moving in and, as it were, setting up camp *. Perhaps that’s why the speaker now seeks refuge in isolation, the safety of being ‘where only the lonely can go’, the prophet’s wilderness…

(*There’s likely to be an autobiographical note here, of course: the world-addressing, world-admonishing proselytiser – ‘so much older then’ – found himself claimed, owned even, as a voice or ‘spokesman’, a mouthpiece for others and their causes.)

On the other hand, while he may go where ‘only the lonely can go’, he’s not unaccompanied:

Hello Mary Lou – Hello Miss Pearl

My fleet footed guides from the underworld

No stars in the sky shine brighter than you

You girls mean business and I do too

‘Hello Mary Lou’ is pretty harmless pop stuff but Jimmy Wages’ ‘Miss Pearl’ sounds more like trouble:

Miss Pearl, Miss Pearl

Daylight recalls you, hang your head, go home…

Whatever she gets up to at night in her ‘underworld’ before daylight ‘recalls her’ we can only guess – the admonishing singer sounds desperate – but Dylan’s False Prophet welcomes his Miss Pearl and Mary Lou as ‘guides from the underworld’, subterranean muses calling to mind Maggie who once came ‘fleet foot Face full of black soot’. Ready now to do business, the three form a threateningly unholy trio – that ‘I do too’ is added with sardonic relish. The Shadow and his ‘guides’ are, as Elvis sang, ‘Lookin’ for trouble’.

That troublesome ‘business’ is intimated in the next verse with its implied declaration of intent, listing the enemies, the targets to be taken on:

I’m the enemy of treason – the enemy of strife

I’m the enemy of the unlived meaningless life

Another intriguing trio: treason, strife and life not fully lived.

Treason, an act of criminal disloyalty, typically to the state, is a crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against the nation (or its sovereign). It implies betrayal, and the voice here might well have in mind both personal experience (reminding us of the ‘world’ that ‘came in’ when he opened up his heart?) and something grander: a political leader (I can’t help but think again of that Trumpean silhouette)who betrays his own nation and all that it stands for. ‘Strife’ might well have a contemporary relevance, too, suggesting as it does, ‘angry or bitter disagreement over fundamental issues’, or ‘vigorous, bitter conflict’: a nation at war with itself – and with a leader at war with his own nation.

The lines, then, condemn betrayal and destructive conflict, while, again, Blake comes to mind in the enmity towards ‘the unlived meaningless life’. Treason and strife are, by implication, life-denying, dark negatives, symptoms or products of the ‘Mind-forg’d manacles’ Blake hears in ‘London’, manacles that a lived, meaningful life would presumably be free of, the ‘chains’ that Rousseau and, later, Marx, saw as denying life and liberty. The speaker’s own freedom is expressed, in fact, in the triumphant separateness of the declaration that follows:

I’m first among equals – second to none

I’m last of the best *

(*Robert Currie’s Genius has a lot to say about this essentially Romantic concept, the creative artist as the One versus the Many, reaching something of an apotheosis in Nietzsche’s notion of ‘Man and Superman’: or ‘Man and The Shadow’?)

Michael Goldberg’s thoughts come to mind here:

The funny thing about ‘False Prophet’ is that when Dylan sings, “I ain’t no false prophet/ I just know what I know,” he could be indicating that he’s actually the real thing…In this new song he also sings,

“I’m the enemy of treason…

“Enemy of strife…

“Enemy of the unlived meaningless life.”

That final line is a theme of the Beats, as I was recently reminded when I read three books by the novelist/memoirist Joyce Johnson, who in her youth was Jack Kerouac’s girlfriend when On the Road, written in 1951, was finally published in 1957. “Enemy of the unlived meaningless life.” It’s as relevant today as a philosophy of life as it ever was.

https://rhythms.com.au/the-shadow-knows-what-he-knows/

The triumphant note is sustained in the next snarled insistence:

you can bury the rest

Bury ‘em naked with their silver and gold

Put ‘em six feet under and then pray for their souls

The implication seems to be that ‘the rest’ are those whose (‘unlived meaningless’) lives have been dedicated to – and wasted – on material, earthly pursuits, falling in love ‘with wealth itself’ (‘I Pity the Poor Immigrant’). Wrong-footing us again, though, a sudden, challenging question, ‘what are you lookin’ at?’, turns into an ambiguous reassurance, ‘There’s nothin’ to see’: he’s invisible now, but, as I suggested earlier, there’s a possible dark undercurrent here, the invitation to ‘walk in the garden’ on the one hand possibly innocently meant but on the other calling to mind the wily serpent (hinted at in the wind’s winding movement, ‘encircling me’)in the Garden of Eden, not actually invisible but, of course, the Devil in disguise, something picked up on a few lines later:

You don’t know me darlin’ – you never would guess

I’m nothing like my ghostly appearance would suggest

Again we’re left wondering about the voice, its tone (Inviting? Reassuring? Deceitful? Boastful?) and its intention: who, exactly are we hearing and ‘What was it [he] wanted?’ Unsettling us still more, the swaggering shifts into vengeful mode again:

I’m here to bring vengeance on somebody’s head

That ‘somebody’s head’ is particularly unnerving – somebody could be anybody – and the ‘ghostly appearance’ is now still more insubstantial, ‘nothin’ to hold’ where a hand should be. The threat of vengeance, on the other hand, is horribly actualised or particularised, stuffing with gold the mouth of the ‘poor Devil’ who can, perhaps, only look up and see, not ever reach or experience the City of God – the new Jerusalem, or Paradise: Paradise lost to Adam and Eve, corrupted by Satan – who himself was hurled out of Heaven:

Put out your hand – there’s nothin’ to hold

Open your mouth – I’ll stuff it with gold

Oh you poor Devil – look up if you will

The City of God is there on the hill

.

This already cryptic, allusive song (addressed by whom, and to whom?) concludes on yet another dense and enigmatic note, loaded with questions:

Hello stranger – Hello and goodbye

You rule the land but so do I

You lusty old mule – you got a poisoned brain

I’m gonna marry you to a ball and chain

You know darlin’ the kind of life that I live

When your smile meets my smile – something’s got to give

I ain’t no false prophet – I’m nobody’s bride

Can’t remember when I was born and I forgot when I died

Ambiguities, uncertainties abound: the voice of a/the Devil, or a/the Devil addressed? Hello – and goodbye – to a stranger who rules the (strange?) land – ‘but so do I’? Once again: ‘I and I’? And that stranger is now a poison-brained ‘lusty old mule’ who’s threatened with marriage, but not a marriage to a wife, instead – vengeance again – an ironic, punishing ‘ball and chain’, calling to mind, for me, Shakespeare’s Lucio who’s punished by, in his words, marriage to ‘a punk!’(By delightful chance, Cockney rhyming slang for ‘wife’ is not, of course, ‘ball and chain’ but ‘trouble and strife’, while in Janis Joplin’s song, Love is the ‘ball and chain’ that drags her down.)

The voice, meanwhile , telling us again that he’s no false prophet, adds that he’s ‘nobody’s bride’ (not ‘Nobody’s Child’), whereas, we might remember (and Dylan reminds us in ‘The Groom’s Still Waiting’) the church is the ‘bride of Christ’ in John’s Gospel. Mischievously, too , the voice, the Prophet or Seer – Blake’s eternal Bard – not only can’t remember when he was born but, weirder still, ‘forgot when I died’.

I don’t think saying “I dont really care” is equivalent to dismissal. Dismissal implies a view that in the broader sense something is not important. “I don’t really care” stresses that it is not of prime importance to me.

The attempt to unlink the meaning of “dismissive” and “not of prime importance” be little more than

a deflection away from the completely

UN-understandable cavalier attitude towards Dylan’s clever lyrics, as well as towards those of the likes of poet William Blake.

Though I have seen my head (grown slightly bald) brought in upon a platter

I am no prophet – and here’s no great matter

I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker

(Eliot: Prufrock)