by Jochen Markhorst

VIII Carmen got a little six Buick

Carmen got a little six Buick, big six Chevrolet car Carmen got a little six Buick, little six Chevrolet car (spoken: My God, what solid power!) And it don't do nothin' but, follow behind Holloway's farmer's plough (Charley Patton - "34 Blues")

The Charley Patton Memorial is one of the stops on the Mississippi Blues Trail and is located at the Holly Ridge Cemetery. Which is about 30 miles from Patton’s home base of Dockery Farms, but Patton died in Indianola, within walking distance of that desolate field. A barren patch of grass, about fifty gravestones and a tree, that’s about it. And that blue sign, of course, at the “entrance”. Charley’s cousin Bessie Turner was there, both on the day of Patton’s death, Saturday 28 April 1934, and at the funeral the following day:

The Charley Patton Memorial is one of the stops on the Mississippi Blues Trail and is located at the Holly Ridge Cemetery. Which is about 30 miles from Patton’s home base of Dockery Farms, but Patton died in Indianola, within walking distance of that desolate field. A barren patch of grass, about fifty gravestones and a tree, that’s about it. And that blue sign, of course, at the “entrance”. Charley’s cousin Bessie Turner was there, both on the day of Patton’s death, Saturday 28 April 1934, and at the funeral the following day:

“[He had] said, ‘Carry me right away from this house to the church and from the church to the cemetery.’ He died that Saturday, and we buried him that Sunday, ’cause he didn’t want to go to an undertaker. That Saturday night they had a big wake for him. A lot of his boys who sang with him were right there too. I’ll never forget the last song they sang, ‘I’ll Meet You in the Sweet Bye and Bye.’ They sang it so beautifully and played the music, you know.”

Bessie also remembers that a marker, some memorial, was placed on his grave. However, an expansion of the nearby cotton mill a few years later extended over that part of the graveyard, and the grave marker disappeared. Much to the frustration of John Fogerty, who in 1990 undertook a number of pilgrimages to Mississippi, looking for the roots of the blues. The cotton mill is long gone, the field is bare and empty. Fortunately, he meets the elderly caretaker Coochie Howard, who remembers where he was shown the grave as a child:

“Coochie took me to a large field, and we walked right up to a place on the edge. Very assuredly, he pointed to a spot in front of us and told me, ‘Charley Patton is buried right there.’ Coochie told me that his mum had pointed out the spot to him when he was four or five years old, and I can only imagine that he’d been looking at that spot for many a decade, because on that day he looked to be in his mid-sixties. I think he said there had been some kind of temporary marker, like a flag or small piece of wood, but that it disappeared long ago.”

(John Fogerty – Fortunate Son, 2015)

Fogerty feels a historical responsibility, opens his wallet and finances the project of blues aficionados Skip Henderson and Jim O’Neal to give Patton the honour he deserves: a memorial service and a shiny gravestone with the inscription

CHARLEY PATTON

APRIL 1891 – APRIL 28, 1934

“THE VOICE OF THE DELTA”

THE FOREMOST PERFORMER OF

EARLY MISSISSIPPI BLUES

WHOSE SONGS BECAME

CORNERSTONES OF AMERICAN

MUSIC

His year of birth may also have been 1885 or 1887. Or even earlier. Blues historian Robert Palmer states in his standard work Deep Blues: “his most likely birthdate is around 1881”, and also investigates the possibility that Charley was not fathered by Bill Patton, but by Henderson Chatmon, the father of Sam, Lonnie and Armenter “Bo Carter” Chatmon, of The Mississippi Sheiks that is. It would explain Charley’s remarkably lighter physique and skin colour; “He looked like a Mexican,” says Hayes McMullen, who often saw Patton play the blues around the Will Dockery plantation in the 1920s. “He wasn’t what you’d call a real coloured fellow,” and he also regularly plays with the Chatmons – who, incidentally, repeatedly claim that Charley is “a relative”.

Anyway, the ceremony took place on 20 July 1991. John Fogerty was there, respectful and stupid in a black suit:

“It was hotter than blazes that day. I sat next to Pops Staples, who was wearing a breezy, all-white linen suit. Me, I had on a dark blazer and tie. Guess who didn’t grow up in Mississippi? The intense heat from days like that was one of the inspirations for my song A Hundred and Ten in the Shade.”

John Fogerty – A Hundred and Ten in the Shade

There is no uncertainty about Patton’s date of death, 28 April 1934. Three months before his death, Patton was still in New York, recording his last songs for Vocation. Ten recordings. Three songs on 30 January, three on 31 January and the last four on 1 February. Not insignificant songs. “Hang It On the Wall”, the re-recording of “Shake It And Break It”, the song Dylan quotes in his 2001 tribute to Patton, “High Water” (Bertha Mason shook it—broke it / Then she hung it on a wall is Dylan’s paraphrase of Charley’s opening line Just shake it, you can break it, you can hang it on the wall); “Oh Death”, not the chilling song DJ Dylan plays in his Theme Time Radio Hour, but just as ominous in context (Patton’s last recording session):

It was soon one morning when Death comes in the room Soon one morning when Death comes in the room Soon one morning when Death comes in the room Lord I know Lord I know my time ain't long

… “High Sheriff Blues”, “Stone Pony Blues”… a century later, Patton’s last songs still echo not only through Dylan’s oeuvre, but are indeed, as his gravestone correctly states, “cornerstones of American Music”. As is the song that Charley recorded on Wednesday, 31 January 1934, halfway through those last three days in New York: “34 Blues”. Patton snarls and growls, painting a picture of life in the American South in 1934, at the height of the Great Depression, and peppering it, as in so many of his songs, with autobiographical details – suggesting that he is lyrically processing his own experiences. They run me from Will Dockery’s, Willie Brown, I want your job, he sings in the second verse, for example – Charley did indeed work for Will Dockery’s company, living and working on the Dockery Plantation. Willie Brown, the man to whom we owe, among other things, “Make Me A Pallet On The Floor” (the song that seems to have inspired the chorus line of “From A Buick 6”) was Charley’s colleague, friend and musical partner, and Patton was, in a sense, just as he was to Robert Johnson, Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters, a kind of mentor to Willie Brown.

The same mix of general zeitgeist and biographical details also seems to apply to the fourth verse, the verse that provides the title for Dylan’s song:

Carmen got a little six Buick, big six Chevrolet car Carmen got a little six Buick, little six Chevrolet car (spoken: My God, what solid power!) And it don't do nothin' but, follow behind Holloway's farmer's plough

Holloway or Halloway also appeared in “Tom Rushen Blues” (1929) and was probably a bootlegger and a friend of Patton’s. It is unknown to whom “Carmen” refers to – most transcribers probably chose the name for lack of a better option (perhaps Charley just pronounces “Chatmon” that way, though it is more likely he says “car men”), but “six Buick” is perfectly understandable. Even for a young Dylan, who, if he did indeed know the relatively unknown song thanks to the Heritage Records release The country blues: volume one (Mississippi), an EP from 1964, would have read the liner notes with interest:

“Patton once lived in Hollandale, a small town south of Clarksdale on U.S. Highway 61, but was born in a place Short recalls as “Murphy Bow”. He died in Memphis in 1934 or 1935 of tetanus resulting from wounds received in a knife fight. Another report claims that Patton also worked as a muleskinner at one stage of his career.”

Only 1934 is correct. Patton never lived in Hollandale (Charley’s half-or-not brother Sam Chatmon did – his Blues Trail Marker is there), “Murphy Bow” does not exist, Charley did not die in Memphis, and certainly not from “tetanus resulting from wounds received in a knife fight”. No serious biographer mentions a career as a muleskinner.

Misinformation, nonsense and slander. It is, in short, a biography after Dylan’s own heart.

To be continued. Next up From A Buick 6 part 9: The Mississippi Delta was shining like a National guitar

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s looking for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

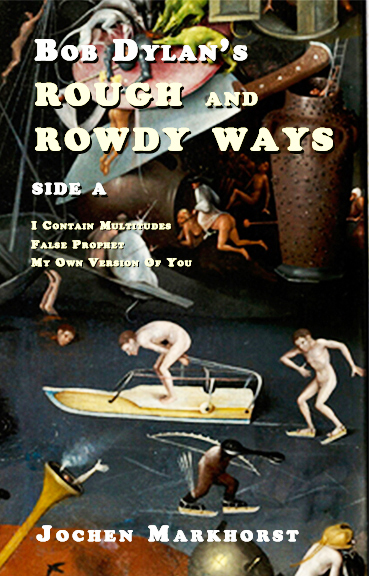

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B

- Bob Dylan’s High Water (for Charley Patton)

- Bob Dylan’s 1971

- Like A Rolling Stone b/w Gates Of Eden: Bob Dylan kicks open the door

- It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry b/w Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues – Bob Dylan’s melancholy blues

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side A