by Jochen Markhorst

Captain Haddock is not introduced until the ninth album, in The Crab With The Golden Claws (Le Crabe aux pinces d’or, 1941). The character is a golden find from Hergé. The impulsive, physical and upbeat Haddock gives an esprit which the colourless, one-dimensional straight man Tintin simply lacks, much like the bloodless Asterix needs a funny man Obelix , like the upright Dean Martin only becomes amusing thanks to Jerry Lewis.

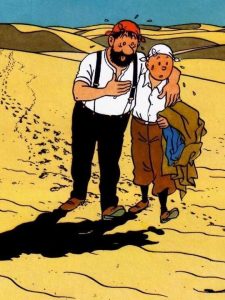

In that first album with Haddock, Hergé immediately creates an iconic image in an iconic scene. On page 26 the plane with Tintin and Haddock makes a crash landing. In Spain, they think. However, a little later they find the skeleton of a dromedary. But, Haddock deduces, that means we are not in Spain. But in the Sahara. And that animal has died of … he is not capable of saying the horrible word and faints when Tintin finishes his sentence: “… died of thirst, of course.”

The nightmare of the excessive drunk Haddock: The Land of Thirst. The next one-and-a-half pages, the distraught sponge only has one line of text. No matter what Tintin says, whatever happens, Haddock vacantly glazes into the distance and mechanically repeats (five times): “The land of thirst …”

It is too hard, too awful, too much of nothing – and that will make a man feel ill at ease.

Horror vacui, the dismay of the captain is called, the fear of the empty. According to Aristotle, a natural science phenomenon that explains why nature does not allow emptiness, and it was a long accepted explanation until it was refuted in 1614 by Evangelista Torricelli’s experiments with vacuum. The term, however, is too good to be wasted and is maintained, for example for the visual arts (the urge to leave nothing empty on a painting) and philosophy (the drive to find an answer for every question).

Dylan’s lyrics do not seem very eloborate and developed, but if we take it seriously, the approach is: psychological. An excess of nothing makes a person tense, insensitive, vicious, deceitful, turns him, in short, into a particularly unpleasant fellow. But, as mentioned, not very elaborated. Presumably this is also one of those lyrics that Dylan quickly rattles out of his old typewriter in the living room of the Big Pink, while the guys from The Band downstairs prepare the stuff for the next session.

All analysts point to T.S. Eliot, because of those two names in the chorus. Valerie and Vivian indeed are the two women in the life of the Nobel Prize-winning British-American writer. As far as Eliot’s work is concerned, Dylan has been pretty dismissive for a long time. Back in 1965 still distinctly hostile, even:

“You read Robert Frost’s The Two Roads, you read T. S. Eliot – you read all that bullshit and that’s just bad, man, It’s not good. It’s not anything hard, it’s just soft-boiled egg shit.”

In 1966 still not very tolerant:

“Carl Sandburg and T. S. Eliot aren’t poets. Their words don’t sing. They don’t come off the paper. They’re just super-romantic refugees who would like to live in the past. I never did admire them.”

And in 1978 Dylan also regards him one of those poets who ‘assume they know something you don’t know’, he thinks Eliot is presumptuous.

In the years that follow, there is apparently a revaluation. In Chronicles T.S. Eliot is mentioned twice. One time outright positively: I liked T. S. Eliot. He was worth reading, and the other time Dylan refers to a work:

T.S. Eliot wrote a poem once where there were people walking to and fro, and everybody taking the opposite direction was appearing to be running away. That’s what it looked like that night and often would for some time to come.

The revaluation is unexpected and at least as remarkable is the small misleading that Dylan undertakes once again. The Eliot text to which Dylan refers does not come from a poem, but from a little known play, from The Family Reunion (1939):

Agatha: In a world of fugitives The person taking the opposite direction Will appear to run away

This careless assignment fits into a pattern; Chronicles is so interspersed with erroneous references and incorrect assignments that it must be a conscious strategy. Dylan also talks about Pericles’ Ideal State Of Democracy (the statesman and general Pericles never wrote any book at all), Tacitus’ Letters to Brutus (which do simply not exist, in the days of Tacitus Brutus had been dead for two hundred years) and he mentions Sophocles’ book on the nature and function of the gods – Sophocles really only writes tragedies and has never written such a book. (Hesiod did, but he lived about three centuries earlier). And also in interviews he frequently screws up names, titles and works.

Not too important. What is interesting is Dylan’s final recognition of T.S. Eliot, and thus indirectly the recognition of what others have been saying for a long time: that there are really some lines to be drawn between both Nobel laureates. Perhaps not content-wise, although some overlap can be found. The famous ‘in the room the women come and go’ from The Love Song Or Alfred J. Prufrock for example, which echoes in “All Along The Watchtower” and the name-check in “Desolation Row”, of course. But the most striking similarity is the working method, the artistic vision of both literary geniuses.

T.S. Eliot is the mint master of the much-quoted immature poets imitate; mature poets steal and practices it, too. His chef d’oeuvre The Waste Lands is an amalgam of paraphrased quotes from both the ‘high-culture’ and the ‘low-culture’, a cross-border masterpiece in which snippets from among others Shakespeare, Wagner, Dante, the Bible but also from popular schlager music and old folk songs are processed. Indeed: exactly like his soul mate Dylan operates – mature poets do steal.

For the masterly, sketchy miniature “Too Much Of Nothing” Dylan seems to have browsed through his Collected Works of Shakespeare, admitting Bible scraps and reflections from Greek myths in between.

The title echoes Much Ado About Nothing, the overall mood breathes King Lear. The alienating word combination abuse a king can only be found once in the world literature; in Shakespeare’s Pericles, Prince Of Tyre (‘Peace, peace, and give experience tongue / They do abuse the king that flatter him’) just like the bizarre to eat fire is unique; the only known corresponding act is Portia’s horrible suicide from the fourth act of Julius Caesar (‘she fell distract and, her attendants absent, swallowed fire’).

Ill at ease is the old-fashioned phrase that Cassio uses in Othello, Leontes in The Winter’s Tale dreads sleeping on a bed of nails, and words like temper, to mock, oblivion and confession have never been used by Dylan before, but are found hundreds of times at Shakespeare.

Only the beautiful line Now, it’s all been done before / It’s all been written in the book does not seem to have been stolen from Shakespeare, but inspired by the Bible: ‘The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.’ (Ecclesiastes 1: 9). And Shakespeare also mentions those waters of oblivion, but the origin is much older, of course; by that, the Ancient Greeks meant the River of Forgetfullness, the Lethe, in the underworld.

The magical beauty of T.S. Eliot’s and Dylan’s works lies within the coherent, poetic image that rises from all these odds and ends, the fascination within its multifaceted nature.

Here, in this song, a fatigue is worded lyrically, that much is clear – but whereof? Is this narrator fed up with materialism, with our consumption-oriented society? Could be. Dylan writes this in 1967, anti-materialism is in the air and those few more serious songs he so seemingly effortlessly plucks from that same air, these days, all describe emptiness, desolation, dissociation: “I’m Not There”, “This Wheel’s On Fire”, “Tears Of Rage”,”One Man’s Loss” and, in a way, “I Shall Be Released” too.

The chorus with greetings to Valerie and Vivian pushes all surrounding imagery in a different direction: to a blues-like lamento of the bitter lover, of a narrator who is discouraged by the empty-headedness, or the disinterest of his beloved.

Confusing is the use of the preposition in the refrain. ‘Send them all my salary / On the waters of oblivion’? Are Vivian and Valerie forgotten, in the dustbin of history, floating around on the waters of oblivion? But then: how would he remember their names, and some moral obligation to send them money? Now the storyteller seems to sing something like ship my money to them disremembered ladies of bygone days – it is either a paradox or an anacoluthon, an ungrammatical sentence.

Well, apparently, the poet prefers a nicely flowing verse line over syntax.

Just as easily the song poet dashes off, once again, a beautiful melody. Since The Basement Tapes Complete (2014) we know for sure that Dylan in these summer months, like a Mozart, has access to an inexhaustible Source of Beautiful Melodies. All those sketches and shreds that are indifferently left behind on the cellar floor … every other artist would have, like a Salieri, thanked God for ideas like “On A Rainy Afternoon”, “I’m Guilty Of Loving You” or “Wild Wolf”, not to mention “Sign On The Cross” and “I’m Not There” – but Wolfgang Amadeus Dylan chews on it once and spits them out again.

“Too Much Of Nothing” escapes the cornfield. It belongs to the fourteen songs manager Albert Grossman takes to the market and it is the first Basement song to get an official release, as Peter, Paul And Mary record it in the late summer of ’67. They even score a hit with it, in November. Some created legend surrounds that recording. The trio changes Vivian into Marion – the name of my aunt, according to Noel ‘Paul’ Stookey – and that is said to have displeased Dylan, would have led to the final estrangement between the poet and the trio that had once established his name (with their recording of “Blowin’ In The Wind”).

That slightly sensational story is eagerly pumped around, among others by a repentant Stookey himself, in Kathleen Mackay’s Intimate Insights from Friends and Fellow Musicians (2010):

“We blew Dylan’s rhyme scheme of Vivian,” Stookey admitted. “Dylan never said anything. We never copped to it. But as a songwriter myself, I can imagine that you write a chorus with alliteration and poetic quality, and it all hangs on the name Vivian, then you hear Marion and say ‘what’s that?’”

Yeah, well. Maybe so. But not very likely. In general, Dylan does not seem very sensitive to what others are doing to his songs. Manfred Mann only phonetically imitates “Quinn The Eskimo”, female colleagues often change she and him and he and her, even at the expense of rhyme, Joan Baez loses the alliteration of “Mama You Been On My Mind” with “Daddy You Been On My Mind” and Dylan himself is just about the first to disrespect his own lyrics; he changes them continuously and is rarely text-proof when, during concerts, he surprises his audience with some forgotten gem from the lower shelves.

An alleged discomfort with the cover by Peter, Paul And Mary can not be attributed to its quality either. It is actually a surprisingly good, beautifully layered version of a song of which they really only had a rather sketchy example. The usual pitfall of the trio – smoothed out, all too clean covers – is avoided by allowing raffled edges; the drummer as well as the harmonica player and the guitarist are unleashed in the couplets, the contrast with the stillness and the superior harmonies in the chorus causes goose bumps (on Late Again, 1968). It is too short, the only downside. And Marion, well, Marion really is not that important.

Among the colleagues the song is not popular anymore. Following Peter, Paul And Mary, there is a short boom, in 1970. The British folk rockers of around Sandy Denny, Fotheringay, record a nice, but somewhat redundant version for their nameless debut album. The same applies to The New Seekers, on their likewise unnamed debut album, also in 1970; nice, but barely different from Peter, Paul And Mary – including Vivian’s name change.

Distinctive is the slightly psychedelic approach of the obscure British progrock group Five Day Rain (1970, again), whose multicoloured cover resurfaces more than thirty years later, as a bonus track on the CD release of their only, self-titled album – it has a very attractive, very timely charm.

Just as dated, but with an exciting soul injection, is the version by Spooky Tooth, on their underrated debut album It’s All About (1968). For the reissue from 1971, with the new title Tobacco Road, “Too Much Of Nothing” is replaced by a successful cover of “The Weight”, an upgrade, indeed.

After 1970 the song evaporates more or less. A single tribute band on YouTube, the inevitable reverence by Robyn Hitchcock (very nice though, a drawling live version from The Basement in Sydney, 2014), but that does not really count – the song is, just like Vivian, floating away on the Waters of Oblivion, drying up in the Land of the Thirst.

You might also enjoy the earlier review of “Too Much of Nothing” on this site.

What else is here?

An index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

There is an alphabetic index to the 550+ Dylan compositions reviewed on the site which you will find it here. There are also 500+ other articles on different issues relating to Dylan. The other subject areas are also shown at the top under the picture.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook which mostly relates to Bob Dylan today. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews.

Jochen, Dylan does not claim to be writing an academic treatise, and who among us would claim that ‘Family Reunion’ is not written in the style of poetry rather than like the informal dialogue of a ‘realist’ play:

The sudden situation in a crowded desert

In a thick smoke, many creatures move

Without direction, for no direction

Leads anywhere but round and round in that vapour

(Eliot:Family Reunion)

A theme echoed in song below with reference to another work of Eliot:

While all the women came and went (Dylan: All Along The Watchtower)

Dylan always mixes things up -whether it’s on purpose or not one is never sure as you point out.

This ‘steam of cinsciousness’ technique has been used long before the Germans attacked Pearl Harbour!

Thanks Larry. But I am pretty confident that, despite lack of academic background or ambition, Dylan is able to tell the difference between a poem and a play.

I do find it intriguing, somehow, this persistence in misattributing titles, authors and genres. It is not pathological, not compulsive (Dylan does attribute correctly, every now and then), but isn’t it bordering on pseudologia fantastica?

À propos T.S.: I am currently sweating over “No Time To Think” (yes, I am fearless and laugh at the face of Immanent Failure). More striking similarities (stylistic, not content-wise) present themselves.

Groeten uit Utrecht,

Jochen

Yes, indeed, but I meant it would be easy for the work to be mistakenly thought a poem in Dylan’s memory …..but who knows…..I ‘m just speculating.

‘Pseudologia fantastica’ is just a five-dollar, 21-letter word for ‘song and dance’ man , is it not?

Good point Larry. Though certainly not for a ‘word and story’ man who presents an autobiography, I’d say. Not that I’m complaining – I really like Chronicles.

Dylan’s trying to cover up the fact that he’s actually a half-breed orphan from the down by the Mexican border.

But I’m sure the truth is bound to come out.

*from down by (lol)

Dylan may have got his orphan story from ‘Duel In The Sun’

starring Gregory Peck.

Did Dylan ever release a 45 of this song? How about an acetate copy ?

Not sure but Dylan himself may have originally written ‘Marion’ in “Too Much Of Nothing” instead of ‘Vivian’ but wanted Peter, Paul, and Mary to keep the change that he made to ‘Vivian’.

See: Rare Original Mayfair Studio: Too Much Of Nothing

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/684/Too-Much-of-Nothing

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan’s Music Box.