by Jochen Markhorst

- More Than Flesh And Blood part I: Lousy poetry

- More Than Flesh And Blood part II: Johnnie, that’s called songwriting

- More Than Flesh And Blood part III: Do right man

- More Than Flesh And Blood part IV: Exquisite corpse

- More Than Flesh And Blood part V: Time regards a snarky bacterium

- More Than Flesh And Blood part VI: Muddy kickin’ in your stall

VII The line dances a jig

I'm going down to find a church that I can understand I need new inspiration and you're only just a man. And with the blackjack table I can't play another hand, The meat you cook for me is bloody rare It's more than flesh and blood can bear

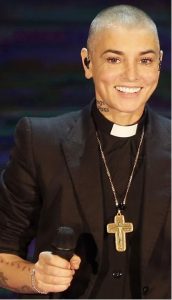

Sinéad O’Connor is a certified Dylan fan. “Slow Train Coming is my favourite album of all time,” she says in 2009, and Street-Legal‘s “Baby Stop Crying” is in her Top 10 favourite songs. Sinead’s congratulatory cum love letter to birthday boy Bob Dylan in 2011, in the Huffington Post, is above all awkward, but the love is real (“I only meant to tell you you’re gorgeous. So have seventy kisses for yourself on Tuesday”).

Sinéad O’Connor is a certified Dylan fan. “Slow Train Coming is my favourite album of all time,” she says in 2009, and Street-Legal‘s “Baby Stop Crying” is in her Top 10 favourite songs. Sinead’s congratulatory cum love letter to birthday boy Bob Dylan in 2011, in the Huffington Post, is above all awkward, but the love is real (“I only meant to tell you you’re gorgeous. So have seventy kisses for yourself on Tuesday”).

Her Dylan covers are almost all successful, and her “I Believe In You” even belongs in the very select club of the most beautiful Dylan covers ever. O’Connor is able to balance on the edge of hysteria, on a good day she has an angelic appearance, she is steeped in Catholicism and her breath-taking voice is ethereal – all of which happen to be excellent qualities for the ultimate performance of “I Believe In You”.

There are – of course – plenty of Dylan traces in her own work, but with some goodwill, you might even assume something like cross-pollination on 2020’s Rough And Rowdy Ways. Dylan’s song “Goodbye Jimmy Reed”, which seems to have Sinéad’s birthplace and homeland Ireland as a backdrop anyway, opens with

I live on a street named after a saint Women in the churches wear powder and paint

It is safe to assume that at least O’Connor’s heart has made a leap; the unconditionally infatuated long-distance admirer may lose herself in the belief that Dylan is making an allusion to her little hit “4th And Vine” from 2012;

Gonna put my pink dress on And do my hair up tight I'm gonna put some eyeshadow on It's gonna look real nice I'm going down to the church On 4th & Vine

It’s a charming song in which the protagonist sings of her happiness: she’s going down to the church today to marry the sweetest man you could find, so gentle and so kind, and beautiful brown eyes he has too – he’s a brown-eyed handsome man. The address of the church, 4th and Vine, is nowhere to be found in Ireland, but seems especially Dylan-inspired (“Positively 4th Street” and Twelfth Street and Vine from “High Water”). And in the last verse her future husband takes her on a buggy ride – just like the protagonist in Dylan’s “Tryin’ To Get To Heaven” does (I was riding in a buggy with Miss Mary-Jane). Of course, the phrase “down to the church” only coincidentally mirrors the opening line of the last verse of “More Than Flesh And Blood”, but still, it’s a nice coincidence.

This last verse is poetically without doubt the strongest verse of the song. Only one weak line, the rest is all right – Dylan the Poet is clearly coming into his own, and has taken the helm from Springs, or so it seems.

The first three lines, the opening tercet, is good old craftsmanship. Three times fourteen syllables, tightly metrical: iambic heptameters – it is the first time in this unsteady, wobbly song text that a unity of three form-retaining, classical lines of poetry is presented. In an archaic, indestructible form, too. The first English translations of Homer’s Illiad and Odyssey were written by George Chapman in these so-called fourteeners (1616), C.S. Lewis disliked the six-foot alexandrines, and argued with infectious enthusiasm for the beauty of the seven-foot heptameter (“The fourteener has a much pleasanter movement, but a totally different one: the line dances a jig”) and Lewis’ friend Tolkien regularly chooses them for the poems in The Lord Of The Rings. As in Treebeard’s “The Ent And The Entwife” (The Two Towers, 1954):

When Spring unfolds the beechen leaf, and sap is in the bough; When light is on the wild-wood stream, and wind is on the brow; When stride is long, and breath is deep, and keen the mountain-air, Come back to me! Come back to me, and say my land is fair!

At least as relieving as the consistent, tight form with “the pleasant movement” is the epic quality of Dylan’s tercet:

I'm going down to find a church that I can understand I need new inspiration and you're only just a man. And with the blackjack table I can't play another hand

… fascinating in content, beautiful, loaded words. Extra charged, of course, because of Dylan’s impending, much-discussed conversion, because of the biographical fact that shortly afterwards he will indeed find a church that he understands and that will give him new inspiration, the Vineyard Christian Fellowship in Tarzana, Los Angeles (unfortunately not on the 4th and Vine).

Nice, this biographical line, but also coincidental, supposedly. The “search for a church” is not elaborated in this song, is not a theme. The associative poetic genius Dylan is probably triggered by previously used, religiously charged jargon like “flesh and blood”, “spirit”, “pure”, “lily and garment” – all Biblical, all leading the stream of consciousness towards church. Perhaps the evergreen “Down To The River To Pray” has popped up, the nineteenth-century classic that survives into the twenty-first century thanks to Alison Krauss’ phenomenal performance on the soundtrack of O Brother, Where Art Thou (Coen Brothers, 2000) and the huge sales success of that soundtrack;

As I went down in the river to pray Studying about that good ol' way And who shall wear the starry crown Good Lord, show me the way

… from the album that tempts Dylan to an unequivocal declaration of love: “I was delighted with this album and even watched the movie” (press conference Rome, 2001). Understandable; the album features almost exclusively beautiful performances of songs that are in Dylan’s heart, songs like “Man Of Constant Sorrow”, “Po’ Lazarus” and “Hard Time Killing Floor”, songs performed by artists who are on a pedestal with Dylan anyway, such as The Stanley Brothers and Emmylou Harris – and Ralph Stanley’s “O Death”, of course.

But in 1978, at a time when he is intensely preoccupied with old blues, it is more likely that the creative part of Dylan’s poetic brain gets hooked on John Lee Hooker, on “Burning Hell” (1959):

I'm going down to the church house Get down on a bended knee Deacon Jones pray for me Deacon Jones please pray for me

Irresistible in the blazing performance by old-timer Tom Jones, on his remarkable old-school masterpiece Praise & Blame (2010). The album opens with a brilliant performance of Dylan’s “What Good Am I?”, so brilliant that it earns him the ultimate compliment from the master himself: Jones is one of twelve artists who are selected by Dylan to come over and sing a Dylan song at the MusiCares event in 2015.

In his autobiography Over The Top And Back (2015) Tom Jones remembers that honour with still bewildered gratitude, in the chapter that he also names What Good Am I. When, after the performances, he sits at a table and listens to that overwhelming speech by Dylan (“the most remarkable piece of oratory I’ve ever heard from a musician”), he sits there “enthralled – enthralled and also amazed to have played a humble part in that evening.”

The rediscovered poetic vein, Dylan’s superior linguistic gifts, John Lee Hooker… it all leads to the most successful tercet of “More Than Flesh And Blood”. For the sake of convenience, let’s ignore the following miss, the lousy poetry of The meat you cook for me is bloody rare. After all, there soon will be a next, last, flash of poetic brilliance.

To be continued. Next up: More Than Flesh And Blood part VIII: Unsaddle, Charley

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits (only German)

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

What else?

You can read about the writers who kindly contribute to Untold Dylan in our About the Authors page. And you can keep an eye on our current series by checking the listings on the home page

You’ll also find, at the top of this page, and index to some of our series established over the years. Series we are currently running include

- The art work of Bob Dylan’s albums

- The Never Ending Tour year by year with recordings

- Bob Dylan and Stephen Crane

- Beautiful Obscurity – the unexpected covers

- All Directions at Once

You’ll find links to all of them on the home page of this site

If you have an article or an idea for an article which could be published on Untold Dylan, please do write to Tony@schools.co.uk with the details – or indeed the article itself.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with getting on for 10,000 members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

O’Connor later converts to Moslem mysticism – “Sufi” poets include Rumi, Khayyam, and Gibran.