by Jochen Markhorst

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit part I: Rose of England

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit part II : A Song Of Ice And Fire

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit part III: I love you, but you’re strange

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit part IV: The Order of the Whirling Dervishes

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit part V: When a sighing begins in the violins

- Love minus zero/No limit part VI: Fair is foul

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit part VII: Your silent mystery

VIII A Study Of Provincial Life

The bridge at midnight trembles

The country doctor rambles

Bankers’ nieces seek perfection /

Expecting all the gifts that wise men bring

The wind howls like a hammer / The night blows cold and rainy

My love she’s like some raven

At my window with a broken wing

Ironically, one of The Smiths’ best-loved songs is one of the most atypical Smiths songs: the hypnotic “How Soon Is Now?” from 1984. It’s the only song in which creative force of nature Johnny Marr lingers on one chord for that long, with a beat and tremolo effect like in Bo Diddley’s “Mona”, smeared across a carpet of guitars. Singer Morrissey’s lyrics, also unusual, put the listener on the wrong track. In any case, “I am the sun and the air” is sung along long enough in the clubs. A self-glorifying opening line that, on second thought, is equally atypical; atypical for Morrissey’s usual self-hatred and self-depreciation, that is. The actual lyrics make a lot more sense:

Ironically, one of The Smiths’ best-loved songs is one of the most atypical Smiths songs: the hypnotic “How Soon Is Now?” from 1984. It’s the only song in which creative force of nature Johnny Marr lingers on one chord for that long, with a beat and tremolo effect like in Bo Diddley’s “Mona”, smeared across a carpet of guitars. Singer Morrissey’s lyrics, also unusual, put the listener on the wrong track. In any case, “I am the sun and the air” is sung along long enough in the clubs. A self-glorifying opening line that, on second thought, is equally atypical; atypical for Morrissey’s usual self-hatred and self-depreciation, that is. The actual lyrics make a lot more sense:

I am the son And the heir Of a shyness that is criminally vulgar I am the son And the heir Of nothing in particular

… now, that’s how we know and love our Morrissey. Still, it is not a Morrissey original; the icon paraphrases another English cultural heritage, from the nineteenth-century bestseller Middlemarch (George Eliot, 1871). From the last chapter of Book I, “Miss Brooke”:

“To be born the son of a Middlemarch manufacturer, and inevitable heir to nothing in particular, while such men as Mainwaring and Vyan—certainly life was a poor business, when a spirited young fellow, with a good appetite for the best of everything, had so poor an outlook.”

Middlemarch – A Study Of Provincial Life is a very English highlight, a psychological novel that always makes it to the lists of “Hundred Most Important Books” or “Hundred Best All-Time Novels” and similar elections. New translations still appear in the 21st century – apparently the work has quite literally centuries-transcending value.

Morrissey being a fan is understandable. The novel tends towards melodrama, plots and subplots are driven by a lot of awkward and unhappy relationship hassles, very English fiddling with social status and social hierarchy and unfathomable hypersensitivities, and George Eliot (Mary Anne Evans’s nom de plume) hews marble phrases like “That’s a pity, now, Josh,” said Raffles, affecting to scratch his head and wrinkle his brows upward as if he were nonplussed, interspersed with by Jove‘s and I shan’t‘s. Much ado, anyway, about pride and prejudice, sense and sensibility, and all.

But that Dylan could be captivated by such an antique through-and-through English weighty tome is rather uncharacteristic. And yet it is very likely: The country doctor rambles / Bankers’ nieces seek perfection… protagonist Tertius Lydgate is an idealistic, somewhat naive country doctor who, against all wisdom, marries Rosamond Vincy, the stunningly beautiful but exasperatingly superficial niece of banker Bulstrode. It is a marriage doomed to failure with an airhead who indeed strives for what she perceives as “perfection” and is quite sensitive to all the gifts that wise men bring – although the latter sounds more like a noncommittal reference to Jesus’ birth than a laborious nod to Middlemarch.

Anyway, the reference to country doctor and banker’s niece is oddly specific, and the combination is nowhere else to be found in the canon. Some analysts think that the “banker’s niece” might be an echo of A Portrait Of A Lady (Henry James, 1881), but have little more argument for this than the otherwise disinterested fact that protagonist Isabel is a niece of retired, wealthy banker Daniel Touchett. No country doctor widely. Although country doctors are popular main and supporting characters in countless novels, television series and films (Kafka creates the most poignant, oppressive country doctor in world literature in Ein Landarzt, for example), they never appear with banker’s nieces.

Middlemarch then. But still, it is unlikely that an unbridled, slightly revved-up, 23-year-old cool hipcat in Greenwich Village like Dylan would have wrestled through those 800 pages, let alone been touched by them. No, that is – with all due respect – more something for a calm lady who radiates peace and reflection, a sphinx-like beauty like the one that has recently been found at Dylan’s side; for Sara, in short.

In this closing couplet, it is not the only hint that a love-struck Dylan incorporates small, intimate insider hints into the lyrics. The opening line, thanks to the candour of Joan Baez in her autobiography, can also be seen in that light:

Sara was afraid of standing on a bridge over water that didn’t move. I thought hers was a much more poetic phobia than my own fear of throwing up and I wrote her a song called “Still Waters at Night.”

… in which Baez incorporates a rather unambiguous reference to Dylan and his Sara in the last verse (“Songs of the vagabond / It’s to you he has sung them”), and indeed processes that poetic phobia in the first verse:

Still waters at night In the darkest of dark But you rise as white As the birch tree's bark Or a pale wolf in winter You look down and shiver At still waters at night

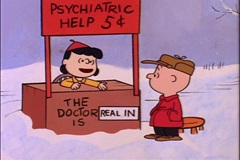

So the lady is trembling on a bridge at night – a not too cryptic paraphrase of The bridge at midnight trembles, of that dreamy opening line of the last verse of “Love Minus Zero”. She probably has “gephyrobia, which is fear of bridges,” as Lucy tries to diagnose with Charlie Brown (in A Charlie Brown Christmas, 1965, Lucy means gephyrophobia). In any case, it is clear: this lady would rather not stand on a trembling bridge at night. She’d rather be at home, curled up in front of the fireplace, with a nice, thick, old-fashioned novel.

By the way: that banker, Mr Bulstrode, is an avid horseman. And he is not the only one in Middlemarch. All through the novel, he does like to hang out with other horsemen, cultivating and discussing all kinds of ceremonies.

To be continued. Next up: Love Minus Zero/No Limit part IX:

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse