by Jochen Markhorst

- Early Roman Kings (2012) part I: Humpty Dumpty had a great fall

- Early Roman Kings (2012) part II: Anything goes

- Early Roman Kings (2012) part III: He had a left like Henry’s hammer

- Early Roman Kings (2012) part IV: You can ring my bell, ring my bell

- Early Roman Kings (2012) part V: I will massacre you

- Early Roman Kings (2012) part VI: The beauty of the flames

- Early Roman Kings (2012) part VII: Ding Dong Daddy

VIII I got the John the Conqueror root

The Tooth Of Crime from 1972 (revised 1996 with a new score, rewritten by T-Bone Burnett) is a fascinating though somewhat depressing, successful musical play by Dylan’s writing partner Sam Shepard about the price of fame. The plot revolves around the decline of celebrated ageing rock star Hoss and the rise of his young rival Crow. The dialogues are – of course – larded with rock quotes, song clichés and winks (“Live outside the Code”, “Good morning little schoolgirl”, “Take out the papers and the trash”), as during the first confrontation between Hoss and Crow:

The Tooth Of Crime from 1972 (revised 1996 with a new score, rewritten by T-Bone Burnett) is a fascinating though somewhat depressing, successful musical play by Dylan’s writing partner Sam Shepard about the price of fame. The plot revolves around the decline of celebrated ageing rock star Hoss and the rise of his young rival Crow. The dialogues are – of course – larded with rock quotes, song clichés and winks (“Live outside the Code”, “Good morning little schoolgirl”, “Take out the papers and the trash”), as during the first confrontation between Hoss and Crow:

HOSS: Old habits break hard.

CROW: You don’t break ’em, you chop ’em off.

HOSS: I didn’t invite you in here to get schooled, bug boy!

CROW: You didn’t invite me, period. I’m yer Backdoor Man.

HOSS: Oh—So, Mr. Willie Dixon still remains on your list? You’re not so far removed as I thought.

… with which Hoss, or rather Sam Shepard, demonstrates a most heartening, accurate, knowledge of music history by attributing “Back Door Man” not to Muddy Waters or The Doors, but to the person who actually wrote it, the legendary Willie Dixon.

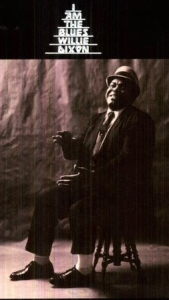

The golden collaboration of Willie Dixon and Muddy Waters starts with the mother of all stop-time blues songs, the grandmother of Dylan’s “Early Roman Kings”: the monument “Hoochie Coochie Man” from 1954. The importance and greatness of the song are undisputed and officially confirmed by now – in 2005 the song is selected for preservation by the US Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry. Like most of Dixon’s classics (“Spoonful”, “I Just Want To Make Love To You”, “Help Me”, “Little Red Rooster” and many more), “Hoochie Coochie Man” demonstrates Dixon’s inordinate talent for achieving an Olympic-size maximum of musical power with a minimum of musical resources. Technically it is simple enough. So simple, in fact, that Dixon could sell it to Muddy Waters during a break behind the scenes in the bathroom of Club Zanzibar in Chicago, as he recounts in his autobiography I Am The Blues (1990):

“We fooled around with “Hoochie Coochie Man” there in the washroom for 15 or 20 minutes. Muddy said, “I’m going to do this song first so I don’t forget it.” He went right up on stage that first night and taught the band the little riff I showed him. He did it first shot and, sure enough, the people went wild over it. He was doing that song until the day he died.”

https://youtu.be/U5QKpsVzndc

And he is also good at explaining why he insists that Muddy Waters take the song. He had written the song some time before, before that meeting, but when he saw Waters perform, he knew enough. Good-looking man, dresses well, attracting the audience in this boastful, manly kind of manner – exactly the kind of black badman Dixon has in mind. The bragging Hoochie Coochie Man is an “epitome of virility”, aided by hoodoo power, women want to submit to him, men want to be him;

“The average person wants to brag about themselves because it makes that individual feel big. These songs make people want to feel like that because they feel like that at heart, anyway. They just haven’t said it so you say it for them.”

Not only did the people go wild over it, as Dixon says, but the song also strikes a chord with colleagues. A few months later Bo Diddley scores a no. 1 hit on the Billboard R&B Chart with the two-sided single “Bo Diddley/I’m A Man” (April ’55). “I’m A Man” is one of the few Diddley songs without the Diddley beat, but Bo’s “betrayal” of his own beat is forgotten after just one bar: he uses the stop-time riff from “Hoochie Coochie Man” as a template, and that’s just as catchy and powerful. Muddy Waters hears it too, and writes his answer song “Mannish Boy”, the title of which is already a jab at Diddley (Bo is fifteen years younger than Muddy). Halfway through, Waters acknowledges his indebtedness to Dixon’s song, elegantly incorporating it into the lyrics:

I'm a man (yeah) I spell M A, child N That represent man No B O, child Y That spell mannish boy I'm a man I'm a full-grown man I'm a man I'm a rollin' stone I'm a man I'm a hoochie-coochie man

It’s a big hit in The States, and remarkably enough Waters’ only UK hit – albeit only thirty-three years later, in 1988, after being used in a Levi’s commercial. But still in its original version, the first recording, played by one of Dylan’s all-time favourite bands. Spin Magazine had Dylan fill out a favourites list in 1988, with sections like “Some Movies I Wish I Was In” and “Three Authors I’d Read Anything By”. Under the heading “Five Bands I Wish I Had Been In” are:

King Oliver Band The Memphis Jug Band Muddy Waters Chicago Band (with Little Walter and Otis Spann) The Country Gentlemen Crosby, Stills & Nash

Okay, “Mannish Boy” is the only recording from the golden Muddy Waters Chicago Band period that doesn’t feature Little Walter (who happened to have other commitments on the day of the recording, May 24, 1955, Bobby Zimmerman’s fourteenth birthday), but the song’s impact on Dylan is crushing nevertheless; “Cold Irons Bound”, on Time Out Of Mind (1997) imitates the atmosphere, colour and menace of the song, “Early Roman Kings” is also musically an unveiled, reverent copy of “Mannish Boy”. Just as “My Wife’s Home Town” (Together Through Life, 2009) is a reprint of Willie Dixon’s “I Just Want To Make Love To You”, by the way – but unlike “Early Roman Kings”, Dixon does get the credit for that one.

More indirectly, but still fairly obvious, also seems to be the influence of “Hoochie Coochie Man”, “I’m A Man” and “Mannish Boy” on the attitude and presence of the protagonist of “Early Roman Kings”. Dixon established it in the early 50s, this monument to the powerful bragger:

I got a black cat bone, I got a mojo too, I got the John the Conqueror root, I’m gonna mess with you, I’m gonna make you girls, Lead me by my hand, Then the world’ll know, I’m the Hoochie Coochie Man.

He is big and powerful, he is aggressive and he steals your girl… he truly is an Early Roman King.

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

The Jewish Sabbath, a day of rest, begins Friday evening and ends Saturday evening.

Christ dies on Friday afternoon, crucified by the Romans before the Jewish Sabbath begins. He rises from the tomb on Sunday, which becomes the Christian Sabbath.

So yes, the sound of the music of “Early Roman Kings” is much the same as ‘Coochie Man” and ”Mannish Boy”, but Dylan lyrics mix matters up, and the song lyrics be not all braggadocio:

Tomorrow’s Friday

We’ll see what it brings

Everybody’s talking

‘Bout the early Roman kings

(Bob Dylan: Early Roman Kings)

So interpreted from the Holy Bible verse below:

In the end of the Sabbath as it began to dawn

Toward the the first day of the week

Came Mary Magdalene and the other Mary

To see the sepulchre ….

“He is not here: for He is risen, as He said

Come see the place where the Lord lay”

(Matthew 28: 1,6 )

* Toward the first day…

Throw in the Passover holiday happening at the time of the crucifixion, and things gets a bit confusing – John changes things around a bit, and claims Jesus did not eat the preparatory Passover meal, other gospels interpreted as saying he did.

A little fun perhaps at the expence of interpreters:

Tomorrow’s Friday

We’ll see what it brings

The Holy Bible states beneath:

Then came the day of the unleavened bread

When the Passover must be killed ….

And when the hour was come, he sat down

And the twelve apostles with Him

(Luke 22: 7,14)

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/177/Early-Roman-Kings

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.