Previously in this series…

- Dirt Road Blues part 1: They going down 61 Highway

- Dirt Road Blues part 2: The troublingest woman I ever seen

- Dirt Road Blues part 3: But your brains are staying south

- Dirt Road Blues part 4: Gross as beetles

- Dirt Road Blues part 5: The purple piper plays his tune

- Dirt Road Blues part 6: Passion on the other hand, is something no one wants.

- Dirt Road Blues part 7: The pale and the leader

- Dirt Road Blues part 8: You Ain’t Going Nowhere

- Dirt Road Blues part 9 : And there will be nothing new in it

by Jochen Markhorst

X Sit down, Winnie

“But, on the other hand, with Dirt Road Blues he made me pull out the original cassette, sample 16 bars and we all played over that.”

(Daniel Lanois, Irish Times, Oct. 24, 1997)

The hun t for the right sound seems to be one of Dylan’s greater concerns in all the decades of his career, and especially in his late work. More important than a chord sequence, more important than semantics, more important than the arrangement and the key and the melody. Its importance to Dylan is a refrain in the interviews, speeches and self-analyses, and close associates like studio staff, producers and session musicians emphasise it again and again. Roughly from Time Out Of Mind onwards, it even seems to become something of an obsession.

The hun t for the right sound seems to be one of Dylan’s greater concerns in all the decades of his career, and especially in his late work. More important than a chord sequence, more important than semantics, more important than the arrangement and the key and the melody. Its importance to Dylan is a refrain in the interviews, speeches and self-analyses, and close associates like studio staff, producers and session musicians emphasise it again and again. Roughly from Time Out Of Mind onwards, it even seems to become something of an obsession.

In the wonderful interview series published by Uncut in the run-up to The Bootleg Series Vol. 8 – Tell Tale Signs (2008), this fascination with sound is a theme with each of the interviewees. Technician Mark Howard, for example, tells:

“He’d tune into this radio station that he could only get between Point Dune and Oxnard. It would just pop up at one point, and it was all these old blues recordings, Little Walter, guys like that. And he’d ask us, “Why do those records sound so great? Why can’t anybody have a record sound like that anymore? Can I have that?” And so, I say, “Yeah, you can get those sounds still.” “Well,” he says, “ that’s the sound I’m thinking of for this record.”

… and he does find it eventually, that sound, with a slight detour. Mark Howard explains it admirably. A few months before the studio sessions, Dylan asks the technical guys whether they could record and mix a live show (House Of Blues, Atlanta, August 3 and 4, 1996). Dylan is peeping over Howard’s shoulder as he mixes the recordings:

“He says, “Hey, Mark, d’ya think you can make my harmonica sound electric on this one?” So I said, yeah, sure, and I took the harmonica off the tape and ran it through this little distortion box, and I played it, and he said, “Wow, that’s great.” So we’re mixing away, and, after he stops playing harmonica, he starts singing into the same mic, and Dylan hears his voice going through this little vocal amp, and he gets really excited about it. “Wow! This is great!” And so I had to remix the whole record, putting this little vocal amp on all of his vocals for the whole show. And that sound became the sound of Time Out Of Mind.”

As producer Daniel Lanois, not only in his interview with the Irish Times, but in Uncut as well, talks again about those “reference records”:

“Bob has a fascination with records from the Forties, Fifities and even further back. We listened to some of these old recordings to see what it was about them that made them compelling.”

Lanois himself recalls old Al Johnson recordings, and in the 2001 interview with Mikal Gilmore for Rolling Stone, Dylan remembers yet another name:

“I familiarized [Lanois] with the way I wanted the songs to sound. I think I played him some Slim Harpo recordings—early stuff like that. He seemed pretty agreeable to it”

Dylan’s memory could be right. Slim Harpo has been a constant over the past half century. In interviews, he regularly cites him as an example of artists who fascinated the adolescent Bobby Zimmerman back in Duluth;

“Up north, at night, you could find these radio stations with no name on the dials, you know, that played pre-rock ’n’ roll things — country blues. We would hear Slim Harpo or Lightnin’ Slim and gospel groups, the Dixie Hummingbirds, the Five Blind Boys of Alabama. I was so far north, I didn’t even know where Alabama was.”

And Dylan remains faithful to Harpo. The throwaway “Seven Days” (1976) already seems to be a rip-off of Slim’s “Mailbox Blues”; for Down In The Groove (1988) Dylan records an unreleased version of “Got Love If You Want It”; on this album Time Out Of Mind, the melody of “’Til I Fell In Love With You” is very similar to “Strange Love”; as DJ of Theme Time Radio Hour Dylan plays “Raining In My Heart” and “I Need Money (Keep Your Alibis)” in the twenty-first century; and in “Murder Most Foul” (2020) Slim drops by again: play “Scratch My Back”, the narrator asks Wolfman Jack.

Enough Slim Harpo traces, in any case, to go along with Dylan’s claim that he is moved by this sound to such an extent that he wants to copy it for Time Out Of Mind. And indeed, the warm underwater sound of the bass, the tinny guitar sound and the metallic vocals with chilly reverb of, for example, “Strange Love” are quite similar to the sound of “Dirt Road Blues”:

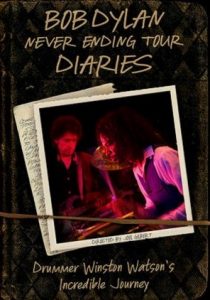

… but still a bit warmer than the rest of Time Out Of Mind. Which can be traced back to that technical fact revealed by Lanois, that only this song used the basic tracks from that mythical demo session, presumably somewhere around that August 1996 live recording in Atlanta. Hence, this is the only song on which Winston Watson’s drums can be heard; unusually, months before the actual studio recordings, Dylan had already been demo-ing new songs, searching for the sound, with members of his touring band. Of which Winston Watson, in Joel Gilbert’s wonderful rockumentary Bob Dylan Never Ending Tour Diaries: Drummer Winston Watson’s Incredible Journey (2009), has a vague recollection:

“So, at one point, he said actually something like to de facto: there’s a sound I’m looking for and we’re not getting it.”

Winston remembers, with a pained face, how desperate he became when Dylan again and again stops rehearsals, unsatisfied, and how he sought to blame himself. When Dylan for the umpteenth time stops a song halfway through, Winston stands up and says (“I with my big mouth”) that he can’t take it anymore.

“This is nerve-wracking. Obviously, there’s something you wanna hear from me that I’m not giving you. I wanna go home. I can’t do this. This is… this is… I can’t.” So Dylan turns around to me, and he says: “Sit down, Winnie.” I thought, oh my God, now I’ve done it, I’ve made Bob Dylan mad. And he puts his cigarette out and he stands up and he says: “Winston is here because he has a certain vibe. I want that vibe. I’m not getting that vibe. This whole room is full of complacency. So if you don’t all wanna go home now, we’re gonna start playing some music in here. Or everybody goes home.”

The harsh pep talk seems to do the job. “Dirt Road Blues” most certainly has a certain vibe, in any case.

To be continued. Next up: Dirt Road Blues part 11 postscript

————-

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

——————————–

Untold Dylan was created in 2008 and is currently published twice a day – sometimes more, sometimes less. Details of some of our series are given at the top of the page and in the Recent Posts list, which appears both on the right side of the page and at the very foot of the page (helpful if you are reading on a phone). Some of our past articles which form part of a series are also included on the home page.

Articles are written by a variety of volunteers and you can read more about them here If you would like to write for Untold Dylan, do email with your idea or article to Tony@schools.co.uk. Our readership is rather large (many thanks to Rolling Stone for help in that regard). Details of some of our past articles are also included on the home page.

We also have a Facebook site with some 14,000 members.

Might I also add that the Slim Harpo track above contains a musical element that Bob Dylan also copied occasionally – that of adding an extra two beats into the occasional bar. It happens for the first time just before the line “The place where we can be alone”. It’s a fiendish thing to follow as a musician unless you are really expecting it and rehearsed in it.

The words get a bit of change in the way they “sound” -sure-, but their meaning(s) is (are) still as solid as when written down.

In short, Dylan did not decide to exclude the lyrics, and leave only the sound of the music.