by Jochen Markhorst

- Million Miles part 1: The closer I get, the farther away I feel

- Million Miles part 2: They kind of write themselves

- Million Miles part 3: And thou didst commit whoredom with them

- Million Miles (1997) part 4: What’s it all coming to?

by Jochen Markhorst

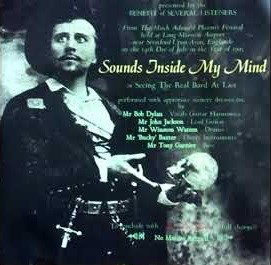

V The sounds inside my mind

Well, I don’t dare close my eyes and I don’t dare wink Maybe in the next life I’ll be able to hear myself think Feel like talking to somebody but I just don’t know who Well, I’m tryin’ to get closer but I’m still a million miles from you

The hint of acceptance from the previous stanza evaporates again already in the fifth stanza. No, this narrator is still pretty upset, still in the penultimate stage of mourning, depression. Disregarding the context, the opening line would seem to be the mantra of a serious case of FOMO, of Fear Of Missing Out. Very serious, even: “I don’t dare close my eyes and I don’t dare wink”; this guy really doesn’t want to miss anything. But within the context, and conditioned by a century of song tradition, we know what is really going on. Bing Crosby already warned about it:

The hint of acceptance from the previous stanza evaporates again already in the fifth stanza. No, this narrator is still pretty upset, still in the penultimate stage of mourning, depression. Disregarding the context, the opening line would seem to be the mantra of a serious case of FOMO, of Fear Of Missing Out. Very serious, even: “I don’t dare close my eyes and I don’t dare wink”; this guy really doesn’t want to miss anything. But within the context, and conditioned by a century of song tradition, we know what is really going on. Bing Crosby already warned about it:

Just when I think that I'm set Just when I've learned to forget I close my eyes, dear, and there you are You keep coming back like a song A song that keeps saying, remember

… in “You Keep Coming Back Like a Song” from 1946, with its truly beautiful title, which eventually inspired the heartbreaking album You Come And Go Like A Pop Song by The Bicycle Thief in 1999. In fact a project from the tragic hero Bob Forrest, whom Dylan fans know mainly from his contribution to the I’m Not There soundtrack, “Moonshiner”, and who, on his ’99 pièce de résistance, expresses with much more credibility the same suffering as Bing Crosby: “I can still see your face” (in “Everyone Asks”).

As Sinatra, too, confesses in ’55 on the unsurpassed heartburn album In The Wee Small Hours in “I See Your Face Before Me” (I close my eyes, and there you are always), as Dylan’s fellow Travelling Wilbury Roy Orbison confided in “Afraid To Sleep” (Can’t close my eyes, afraid to sleep / Cause when I do I would only dream of you, 1965)… we know by now what it means when a Victim of Love says he dare not close his eyes. The choice of these particular words, though, seems to be triggered by Henry Rollins – not for the first and not for the last time on Time Out Of Mind.

Rollins’ trigger, in turn, is of course more intense and more personal than fictional heartbreak. Rollins writes Now Watch Him Die (1993) after witnessing how his friend Joe Cole dies brutally and senselessly when he and Joe are victims of a robbery; before Henry’s eyes Joe is shot through the head. In the literary coping therewith, Rollins uses the word combination a few times to express a similar fear (“I close my eyes and I’m in the room with Joe’s body”, for instance), just as Dylan’s continuation Feel like talking to somebody but I just don’t know who seems to be inspired by it: “No one is anyone I can talk to,” Rollins writes, for instance, and “I look at the phone thinking about calling out there / There’s no one to call.”

The other distorted sense is less unambiguous. The narrator shares the inability to hear himself think with an earlier protagonist in Dylan’s oeuvre, with the I-person from “One Too Many Mornings” (1964):

An’ the silent night will shatter From the sounds inside my mind

… at least, if we assume that it’s not interfering noise, preventing him to hear himself think. In any case, that is the scenario that Henry Rollins invokes time and again in his work. The choppers are so loud I can’t even hear myself think, for example (in “Art To Choke Hearts”, 1986), or I have the music cranking in my headphones so I can hear myself think over the caterwaul of my fellow masticators. It is disturbing enough, the state of Henry Rollins’ mind, but it is to be feared that Dylan’s narrators are even worse off – there it is the inner chaos that makes following one’s own thoughts impossible. In “Million Miles”, a threatening inner chaos, even; an addition like maybe in the next life and the ultimate loneliness of feel like talking to somebody but I just don’t know who suggest suicidal despair.

Seeing, hearing, feeling… his senses have been stripped, the poor soul. And apparently ready to fade too. But the cheerful, carefree connotation that Mr. Tambourine Man’s friend communicates with those words is completely missing here. This is the fourth song on Time Out Of Mind, and the motifs begin to emerge. Walking is one (preferably at night, or so it seems), world weariness, or rather life weariness a second one, and the disturbed perception, like here in this stanza of “Million Miles”, a third one. This motif returns in almost every song, with the devastating power of mental illness even. “I’m beginning to hear voices,” the man in “Cold Irons Bound” notices. “Insanity is smashing up against my soul,” says the narrator in the closing song “Highlands” – a superlative of the announcement “my brain is so wired” in the opening song “Love Sick”. Prior to “Million Miles”, in “Standing In The Doorway”, we have already heard the narrator complain that he feels “sick in the head”, and before that, in “Dirt Road Blues”, concerns about mental health and the reliability of his sensory perceptions are justified as well.

After the first four songs on Time Out Of Mind, all three motifs keep returning. The weariness less pronounced, but unmistakable. They all walk, sometimes in combination with the third motif, the mental crisis: “I’m strolling through the lonely graveyard of my mind,” says the pitiful wretch in song no. 10, in “Can’t Wait”. By then we have met his fellow sufferers one by one. Fellow sufferers whose nerves are exploding (“‘Til I Fell In Love With You”), whose nerves are vacant and numb (“Not Dark Yet”), who don’t even know what “all right” means (“Tryin’ To Get To Heaven”)… no, our narrator from “Million Miles” may be lonely, but he is not alone. Any one of those men is a suitable conversation partner for a guy who feels like talking to somebody but just doesn’t know who.

Indeed. But then again, every one of those possible conversation partners is probably a million miles away, too.

To be continued. Next up Million Miles part 6: Like a wagon wheel

————

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang