- Million Miles part 1: The closer I get, the farther away I feel

- Million Miles part 2: They kind of write themselves

- Million Miles part 3: And thou didst commit whoredom with them

- Million Miles part 4: What’s it all coming to?

- Million Miles part 5: The sounds inside my mind

- Million Miles part 6: Like a Wagon Wheel

Million Miles (1997) part 7

by Jochen Markhorst

VII Songs that float in a luminous haze

Well, there’s voices in the night trying to be heard

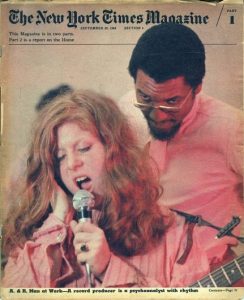

I’m sitting here listening to every mind-polluting word

Suddenly producer Tom Wilson is gone and replaced by Bob Johnston. In January ’65, Dylan and Wilson passionately and harmoniously complete the first album of the mercurial trio, Bringing It All Back Home. When Dylan is over in England to be called Judas, Wilson is in New York doing overdubs for the intended single “If You Gotta Go, Go Now” (21 May 1965). And when Dylan returns, the men just get to work on the next masterpiece, on Highway 61 Revisited. Two days of recording, Wilson is still in the control room (15 and 16 June), the days when the final recording of “Like A Rolling Stone” is realised. No small feat either.

Suddenly producer Tom Wilson is gone and replaced by Bob Johnston. In January ’65, Dylan and Wilson passionately and harmoniously complete the first album of the mercurial trio, Bringing It All Back Home. When Dylan is over in England to be called Judas, Wilson is in New York doing overdubs for the intended single “If You Gotta Go, Go Now” (21 May 1965). And when Dylan returns, the men just get to work on the next masterpiece, on Highway 61 Revisited. Two days of recording, Wilson is still in the control room (15 and 16 June), the days when the final recording of “Like A Rolling Stone” is realised. No small feat either.

But still Wilson’s swan song. On the third day of recording, 29 July, Bob Johnston is suddenly at the controls. Dylan acts like he doesn’t know why, when Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner asks him four years later;

JW: Why did you make the change of producers from Tom Wilson to Bob Johnston?

BD: Well, I can’t remember, Jann. I can’t remember… All I know is that I was out recording one day, and Tom had always been there – I had no reason to think he wasn’t going to be there – and I looked up one day and Bob was there. (Laughs)

Evasive and not very credible. It is not too plausible that Dylan, like a submissive wage slave, would let the Bosses Above Him decide with whom he must cooperate. Johnston doesn’t know the ins and outs of it either, but he has an educated guess:

“His producer was Tom Wilson then. Gallagher called me in the office said, “We’re getting rid of Tom Wilson.” He didn’t say why but maybe it was because Albert Grossman said he didn’t like him, and I don’t think Dylan liked him. I don’t know, but he never said anything about it.”

Wilson will never meet Dylan himself again, but indirectly, as a producer of other artists, still often enough, of course. In 1967, for instance, when he and Nico record one of Dylan’s masterly throwaways, “I’ll Keep It With Mine”. And even more indirectly in 1970, when Wilson is the producer for the fifth LP of the infectious weirdos from San Francisco, for CJ Fish of Country Joe and the Fish. The final track of Side One will have taken him back in time a few years;

Hey Bobby, where you been ? We missed you out on the streets I hear you've got yourself another scene, it's called a retreat I can still remember days when men were men I know it's difficult for you to remember way back then , hey

… “Hey Bobby”, the slightly awkward call for Dylan to return to the front, set to the same chord progression as “Like A Rolling Stone” is set, to “La Bamba”.

In Dylan’s 2004 autobiography Chronicles, it is a theme. In Chapter 3, “New Morning”, Dylan looks back on a dark period in his life, the period around 1970, the years when Country Joe McDonald (among others) makes his pathetic appeal. The bard leaves no doubt about how enormously unpleasant he found it to be promoted “as the mouthpiece, spokesman, or even conscience of a generation”. And how disruptive the consequences were. In Woodstock, he and his family were harassed by fans, followers and other nutcases, “goons were breaking into our place all hours of the night”, in the press they kept portraying him as a kind of High Priest of Protest, colleagues like Robbie Robertson were waiting for his next move, waiting to show them where he’s “gonna take it”.

It is very, very unpleasant. “It would have driven anybody mad,” Dylan writes. All the more so because he does not recognise himself at all in that image, nor does he have the ambition to be a spokesman of any kind. “I would tell them repeatedly that I was not a spokesman for anything or anybody and that I was only a musician,” but that doesn’t help, of course. It seems to frustrate Dylan still thirty years later, when he writes these words. “I really was never any more than what I was – a folk musician who gazed into the gray mist with tear-blinded eyes and made up songs that floated in a luminous haze.”

And even more than Robbie Robertson’s docility, even more than Country Joe’s “Hey Bobby” or David Bowie’s brilliant harangue, “Song For Bob Dylan”, he will have been irritated by the embarrassing “protest song” of his former life partner Joan Baez.

“Joan Baez recorded a protest song about me that was getting big play, challenging me to get with it — come out and take charge, lead the masses — be an advocate, lead the crusade. The song called out to me from the radio like a public service announcement.”

Dylan refers to Baez’s open letter “To Bobby”, the much-discussed song from the very mediocre album whose title also signals painful naiveté: Come From The Shadows (1972). In the self-written song, Baez does her best to wrap her appeal in dylanesque rhyme patterns and eloquence. Like in the third verse;

Perhaps the pictures in the Times could no longer be put in rhymes When all the eyes of starving children are wide open You cast aside the cursed crown and put your magic into a sound That made me think your heart was aching or even broken

… four lines that are “actually” six lines, judging by the aabccb-rhyme scheme (Times-rhymes-open / crown-sound-broken), just like “Love Minus Zero” and “I Don’t Believe You”, dylanesque assonant rhyme (open-broken, for instance) and a dylanesque image like a cursed crown. From a technical point of view just fine – but unfortunately Baez’ foible for toe-curling melodrama, for kitschy images like the wide-open eyes of the starving children, is dominant. A foible she unfortunately also demonstrates in the possibly even more pathetic chorus, in

Do you hear the voices in the night, Bobby? They're crying for you See the children in the morning light, Bobby They're dying

“Now listen,” Dylan says in his 2015 MusiCares speech, “I’m not ever going to disparage another songwriter.” And indeed, in this same speech, he does speak of Baez only with praise, with love and admiration (“A woman of devastating honesty. And for her kind of love and devotion, I could never pay that back”). Elegant. But probably no one in the audience, and not even Baez herself, would have blamed Dylan if, more than forty years after the fact, he had given his opinion about “To Bobby”.

However, exactly halfway between Baez’s 1972 song and Dylan’s 2015 speech, he seems to be venting his opinion, subtly of course. In the last verse of “Million Miles”, which Dylan recorded in January ’97, he echoes the chorus of “To Bobby”:

Well, there’s voices in the night trying to be heard I’m sitting here listening to every mind-polluting word

… in which, in this scenario, he expresses his opinion somewhat less elegantly (every mind-polluting word). Not unequivocal, however. The metaphor “voices in the night” is hardly unique (The Eagles’ “Witchy Woman” comes to mind, and Joni Mitchell’s “I Think I Understand”), but it is still so unusual that it seems obvious that Dylan himself would think of Baez’s whiny refrain. And apart from that, it fits perfectly on an album full of wandering protagonists with confused sensory impressions, on a record on which one protagonist confesses “I’m beginning to hear voices and there’s no one around” (“Cold Irons Bound”), a second wonders if he hears someone’s distant cry (“Love Sick”) and a third, in “Not Dark Yet”, sighs: “Don’t even hear a murmur of a prayer”.

But still. The expression “voices in the night” is just a bit too distinctive. And after all, “To Bobby” is, for all its awkwardness, one of those songs that float in a luminous haze.

To be continued. Next up Million Miles part 8: Write twenty verses while you’re in The Zone

———-

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang