From A Buick 6 part 7

by Jochen Markhorst

VII The steam shovel and the dump truck

Well, you know I need a steam shovel, mama, to keep away the dead

I need a dump truck, baby, to unload my head

She brings me everything and more, and just like I said

Well, if I go down dyin', you know she's

bound to put a blanket on my bed

“ I was just extending the line,” says Dylan in that 2015 MusiCares speech, “the most remarkable piece of oratory I’ve ever heard from a musician,” in the words of Tom Jones. In the middle section of that breathtaking speech, Dylan dwells at length on the roots of his songs: “It all came out of traditional music,” and then names ten songs that were templates for songs such as “Blowin’ In The Wind”, “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”, “Boots Of Spanish Leather”, “The Times They Are A-Changin’”, “Maggie’s Farm”, “Highway 61 Revisited” and “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”, so hardly the minor ditties, all in all. The ten songs are:

“ I was just extending the line,” says Dylan in that 2015 MusiCares speech, “the most remarkable piece of oratory I’ve ever heard from a musician,” in the words of Tom Jones. In the middle section of that breathtaking speech, Dylan dwells at length on the roots of his songs: “It all came out of traditional music,” and then names ten songs that were templates for songs such as “Blowin’ In The Wind”, “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”, “Boots Of Spanish Leather”, “The Times They Are A-Changin’”, “Maggie’s Farm”, “Highway 61 Revisited” and “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”, so hardly the minor ditties, all in all. The ten songs are:

- “John Henry”

- “Key to the Highway”

- “Sail Away Ladies”

- “Roll the Cotton Down”

- “Come On in My Kitchen”

- “Chisholm Trail”

- “Death Of Floyd Collins”

- “Come All You Fair and Tender Ladies”

- “Pretty Boy Floyd”

- “Deep Ellum Blues”

All those “Come all ye” songs led to The Times, Dylan explains, and the link between, say, “Roll the Cotton Down” and “Maggie’s Farm” is apparent as well. Less clear is why he points to “John Henry” as the inspiration for “Blowin’ In The Wind” (the echoes of “John Henry” in “Tell Me Momma” are much clearer: Yes, you got your steam drill, now you’re lookin’ for some kid / To get it to work for you like your nine-pound hammer did), but the gist of Dylan’s argument is clear: those traditional songs give him the song structures, the flow and the lingo, the idiom.

Woody Guthrie’s influence is emphasised twice in that list (“Chisholm Trail” and “Pretty Boy Floyd”), and Dylan is still holding back; he could easily have mentioned ten more Guthrie titles. “Dust Bowl Blues”, for example:

I had a gal, and she was young and sweet, I had a gal, and she was young and sweet, But a dust storm buried her sixteen hundred feet. She was a good gal, long, tall and stout, Yes, she was a good gal, long, tall and stout, I had to get a steam shovel just to dig my darlin' out

… the song that, together with “Pretty Boy Floyd”, was added to the 1964 RCA Victor Records reissue of Woody’s most successful album, Dust Bowl Ballads from 1940. By 1965, when Dylan recorded “From A Buick 6”, the archaic steam shovel had long since been discarded and replaced by petrol or diesel excavators. But it was still relevant enough for Dylan. “There was a precedent,” he says in that 2015 speech, “I just opened up a different door in a different kind of way. It’s just different, saying the same thing.” I’m just continuing the line, says Dylan.

And so the steam shovel survives – with the same grim connotation as in Woody’s song, incidentally: Guthrie uses the steam shovel to dig up the corpse of his beloved, which inspires Dylan to write “I need a steam shovel, mama, to keep away the dead.”

Appropriately enough, Dylan establishes himself in the next line, with the unusual dump truck, as the next link in the chain: the link to Guthrie, Diddley and Dylan disciple Joe Strummer.

Sometime in the summer of 1975, John Mellor chose the name by which we have all known him ever since: “Joe Strummer”. In the years before that, the immortal combat rocker, frontman of The Clash, didn’t introduce himself as “John” either, but as “Woody”, which is said to be meant as a tribute to Woody Guthrie. A bit of historical revisionism that was alright with Strummer, but not with biographer Chris Salewicz:

“In the mythology of Joe Strummer, his “Woody” nickname has always been said to be a tribute to folksinger Woody Guthrie, which Joe was happy to go along with—but there seems to have been a much simpler, rather less romantic explanation. It’s easy to see how Woolly could mutate to the more direct Woody.”

(Chris Salewicz – Redemption Song: The Ballad of Joe Strummer, 2006)

… because during his brief art school career in Wales, he formed a band whose members gave themselves absurd names, à la Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band. John Mellor called himself “Woolly Census”, later changing it to “Woody”, according to fellow band member Paul ‘Pablo Labritain’ Buck: “Next time I saw him after he’d left school, he said ‘No, no: I’m Woody now.’ It was just kids’ stuff.” His idol at the time was still Dylan (“He’d sit there with a guitar, playing things like “Blowin’ in the Wind” during the morning break. He was a huge fan of Bob Dylan. Sometimes it would be hard to get him back to work after that”), but that more or less accidental name change ultimately ignited Strummer’s deep, lived-through love of Woody Guthrie, according to fellow student Richard Frame:

“Frame remembered scouring specialist record shops in Cardiff with Woody. “He was looking for Woody Guthrie records,” he said, as though John Mellor were now trying to source the origins of his nickname.”

Strummer recognises the socio-political engagement, morality, struggle for justice and focus on community, admires Guthrie’s songwriting instinct of course, and has since liked to see himself as a successor – he perpetuates the myth that he named himself after Woody Guthrie at the time and copies signature touches such as writing slogans on his guitar – he remains a true heir in word and deed until the end.

Dylan, however, remains a poetic muse. Whether it is a Dylanesque homage to an actor from the Golden Age of Cinema (to Montgomery Clift in “The Right Profile”, 1979) or a Dylanesque verse as in “Go Down Moses”;

Once I got to the mountain top, everywhere I could see Prairie full of lost souls running from the priests of iniquity Where the hell was Elijah? Well, what do you do when the prophecy came was true?

… which sounds like a forgotten outtake from Dylan’s Infidels, or the less subtle name checks such as in “Coma Girl” (As the nineteenth hour was falling upon Desolation Row / Some outlaw band had the last drop on the go) and in the title of “Leopardskin Limousines”: from The Clash days in the 1970s to his last album Streetcore (released posthumously in 2003), we continue to hear more Dylan than Guthrie echoes. As in “Passport To Detroit” (1989), a song title that seems just as unrelated as “From A Buick 6” (neither “passport” nor “Detroit” appear in the lyrics):

In old Genoa Behind some dump truck drivers door There was a lady who was dressed up Like Marlene before the war

… in which Grandmaster Dylan will undoubtedly nod approvingly at the rhyme find old Genoa – before the war and at the supporting role for Marlene Dietrich, but just as striking is “dump truck”; Joe is an English lad – and an Englishman would sooner call a dump truck a tip lorry. Except, of course, if you like Joe “Woody” Strummer have been playing Dylan songs since you first learned to hold a guitar. And if Dylan’s lyrics are your guiding light:

“When Fisherman’s Blues by the Waterboys came out, I thought it was a great song. I played it to him. He said, “The problem is he’s saying what he feels. Bob Dylan doesn’t say, “I walked through a door.” He says, “There was smoke in the air.” He doesn’t say the obvious. This guy’s hitting it on the head. It’s just not interesting.”

(manager Gerry Harrington in Salewicz’ Strummer biography Redemption Song)

Still, there are limits to Strummer’s docility. Hidden at the end of that thorough biography from 2006, on page 440, bassist Zander Schloss reveals a remarkable fun fact from 1989, which takes place around the recording of the album on which “Passport To Detroit” can be found, Earthquake Weather:

Bob Dylan dropped by, once leaving a tape of a song he thought Joe might like to try out. For his usual complex set of reasons, Joe never listened to it. “I think it was Joe not wanting to deal with it,” said Zander. “It stayed in the drawer.”

For Joe Strummer may well be the next link in the chain, the next guy extending the line – but he was also his own man. Joe goes through a different door in a different kind of way. It is intriguing though: somewhere in a drawer lies a Dylan song that Dylan thought would be good for the legendary frontman of The Clash. Joe has been dead for more than twenty years now. Where is that drawer?

To be continued. Next up From A Buick 6 part 8: Carmen got a little six Buick

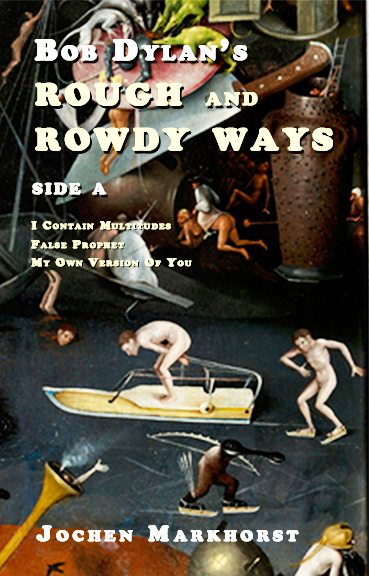

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B

- Bob Dylan’s High Water (for Charley Patton)

- Bob Dylan’s 1971

- Like A Rolling Stone b/w Gates Of Eden: Bob Dylan kicks open the door

- It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry b/w Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues – Bob Dylan’s melancholy blues

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side A