You’re A Big Girl Now (1975)

by Jochen Markhorst

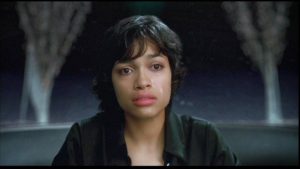

The Men In Black and a bunch of evil aliens are searching for ‘The Light’ of the planet Zartha, which eventually turns out to be a semi-divine creature in an attractive human form: Laura Vasquez, played by Rosario Dawson. That is tough luck for Agent Will Smith, who has an understandable crush on Laura. Laura, too, has a hard time saying goodbye, and instantly rain rustles down gently. Agent K, Tommy Lee Jones, knows why:

The Men In Black and a bunch of evil aliens are searching for ‘The Light’ of the planet Zartha, which eventually turns out to be a semi-divine creature in an attractive human form: Laura Vasquez, played by Rosario Dawson. That is tough luck for Agent Will Smith, who has an understandable crush on Laura. Laura, too, has a hard time saying goodbye, and instantly rain rustles down gently. Agent K, Tommy Lee Jones, knows why:

“You are a Zarthan. When you get sad, it always seems to rain.” “Lots of people get sad when it rains,” Laura argues. K clarifies, pitying: “It rains because you’re sad, baby.”

Rain is an indestructible metaphor to the esteemed ladies and gentlemen poets. And as a rule it symbolizes suffering and calamity; even in the Bible, where decors are generally arid, dry and destitute, rain usually means misery. The Lord drowns the whole world in forty days and nights of rain, lets fire, sulfur and hailstones rain down, rains lash sassy Egyptians, it rains powder and dust upon idolaters, but paradoxically God thunders, when He is very, very angry, that He will shut up heaven that there be no rain.

The negative connotation penetrates world literature and of course also the work of the songwriters. It rains in the heart of Buddy Holly (“Raining In My Heart”, 1959, written by the Bryant couple), the “Rain” of The Beatles causes people to flee, Sinatra’s life is a cold rainy day after the departure of his sweetheart, (“Here’s That Rainy Day”) and the Gershwin brothers comfort and console that every dream home has its heartache (“Some Rain Must Fall”, 1921).

It also rains in Dylan’s catalog. Dozens of times. In the early years, the poet usually brings it down to sharpen a dark, threatening and sometimes even gruesome content. The heavy rain in “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”, of course, the body of Emmett Till is dragged to the river through a bloody, red rain, the Walls Of Red Wing are all the more despondent when the rain hits heavily on the roofs and filthy, pouring rain pierces Hollis Brown.

In the mid-sixties, Dylan succumbs to the age-old, familiar connection of rain with heartbreak and related amorous misery. The protagonist from “Just Like A Woman” is in the rain, cats and dogs would come down if not for you, the converted Christian leaves his so-called friends lonely and alone in the pouring rain (“I Believe In You”), he is rolling through the rain when his lover has left him (“Dirt Road Blues”).

The narrator in “You’re A Big Girl Now” is back in the rain. That, plus the little girl – big girl mirroring, leads the listener involuntarily back to eight years earlier, to the I-figure from “Just Like A Woman”, who is in the rain after yet another stranded love affair. Then, after Sad-Eyed Sara, the sun shines for the singer – up until Blood On The Tracks, the album on which Dylan is back in the rain and, by his own account, expresses pain.

Dylan confesses this shortly after the release of the album, in the radio interview with old friend Mary Travers (Peter, Paul and Mary), April 26, 1975: “A lot of people tell me they enjoy that album. It’s hard for me to relate to that. I mean, you know, people enjoying the type of pain.”

That statement is in line with son Jakob’s famous quote in The New York Times, May 2010: “When I’m listening to ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’, I’m grooving along just like you. But when I’m listening to ‘Blood on the Tracks’, that’s about my parents.”

Jakob’s most quoted words, though meanwhile the nuance is lost that it is only an indirect quotation. It is true that it is printed in that interview with Jakob, but precisely this quote only appears in an intermezzo in which journalist DeCurtis notes what Andrew Slater, the former manager of Jakob’s band The Wallflowers, has told him about what Jakob supposedly said years earlier. It is hearsay, not words that the journalist has recorded from the mouth of Jakob Dylan.

Still, pain. The sharpest and most poignant that pain seems to be expressed in the final lines of “You’re A Big Girl Now”, in

I’m going out of my mind, oh, oh With a pain that stops and starts Like a corkscrew to my heart Ever since we’ve been apart

The corkscrew metaphor is masterful. Only the harshest reviewer can hold back the tears here and the image resonates; it is a frequently cited verse line among biographers, reviewers and fans. In doing so, everyone follows Jakob’s alleged observation and Dylan’s own outpouring: the poet provides a rare, candid insight into the innermost workings of his soul, the man Bob Dylan reveals the pain he feels in losing his marital happiness, in losing Sara.

Sixteen years later, this openness is bothering him and he tries to draw the curtain again. Dylan’s tirade in the book accompanying the collection Biograph clashes head-on with Jakob’s statement and Dylan’s own commentary from 1975. Completely foolish is the thought that he would tell something from his own life. If you think so, you are nuts, he fulminates:

“I read that this was supposed to be about my wife. I wish somebody would ask me first before they go ahead and print stuff like that. I mean, it couldn’t be about anybody else but my wife, right? Stupid and misleading jerks these interpreters sometimes are … I don’t write confessional songs. Emotions got nothing to do with it. It only seems so, like it seems that Laurence Olivier is Hamlet… well, actually I did write one once and it wasnt very good – it was a mistake to record it and I regret it… back there somewhere on maybe my third or fourth album.”

Dylan refers to the painful song “Ballad In Plain D“, the vicious, nasty attack against Suze Rotolo and especially her sister Carla. This mea culpa at the end, however, hardly distracts from the main idea of this comment: suddenly the poet claims that he would never ever write about his own marriage – or about other private disputes.

For the Biograph collection box, Dylan has opted for a New York recording of “You’re A Big Girl Now”. That is a chillingly beautiful recording from September ’74, scantily instrumented, but with the tasteful, restrained organ by Paul Griffin, the virtuoso who so often manages to press the right key on Dylan recordings (the piano parts on “One Of Us Must Know” and “Like A Rolling Stone”, for example) and with the steel guitar of Buddy Cage, the master of New Riders Of The Purple Sage. The recording sessions clearly inspire Cage: on the next New Riders album there is a nice cover of “Farewell Angelina” (Oh, What A Mighty Time, produced by Bob Johnston).

When the recordings in New York have been completed and the album is ready to be pressed, Dylan goes to his family in Minnesota for Christmas. Brother David hears the pressings and has criticism which the maestro supports.

The release is hastily postponed, and on 27 and 30 December 1974 Dylan re-records five of the ten songs with local musicians under the direction of David Zimmerman – including “You’re A Big Girl Now”.

The accompaniment on the Minneapolis version is less desolate, even opens with an elegant, almost sweet guitar mosaic, but that contrasts beautifully with Dylan’s distraught recital – it is indeed difficult to choose between the two versions. Brother David may have stumbled over the uniformity of the ten tracks, not so much over the beauty of the individual tracks. Bootlegs like Blood On The Outtakes and Blood On The Tapes, and the official release More Blood, More Tracks feed that thought; ten songs in a row where the sound is  predominantly dictated by Dylan’s guitar and the bass of Tony Brown, does not detract from the otherwise undisputed splendor of the songs, but the impact of the album as a whole is affected (not to mention the incessant tickling of Dylan’s cufflinks against his guitar).

predominantly dictated by Dylan’s guitar and the bass of Tony Brown, does not detract from the otherwise undisputed splendor of the songs, but the impact of the album as a whole is affected (not to mention the incessant tickling of Dylan’s cufflinks against his guitar).

The lyrics have a peculiar magic. The many acetous literators who, after the awarding the Nobel Prize, argue that a song is not literature because it can not exist without the performance, are usually painfully ill-taught. Apart from the fact that one may also claim the same about the Nobel Prize-winning theater writers: the majority of Dylan’s lyrics are powerful enough to stimulate, touch or move even without the performance, easily survive on naked paper. But every now and then it does need the performance, like here, at “You’re A Big Girl Now”.

A few sparkling direct hits the lyrics certainly contain. The opening lines, for example, which immediately stimulate the listener and the reader;

Our conversation was short and sweet It nearly swept me off-a my feet

These words promise the story of a man who has fallen madly in love. To be swept off my feet is the ecstatic variant to express ‘confusion’ – in a positive, amorous sense. In the following lines, however, it suddenly becomes clear that the conversation was an exit conversation, that the narrator has been dumped and that he has lost the ground under his feet. The aforementioned corkscrew metaphor is another literary bull’s eye, but otherwise … on paper the lyrics indeed reek of melodrama and overdone pathos, with clichéd exclamations like I’m going out of mind or I can change, I swear.

But then: the performance. Dylan the singer expresses a pain and a regret in his words, which also bestow an authenticity, truthfulness and loneliness upon the less stimulating fragments – it may not be Nobelworthy literature, but Art with a capital A it certainly is.

The song has a beautiful melody, the notes are in the right place to enhance the dramatic, melancholy lyrical content, but still: that performance is decisive, as the the many unsuccessful covers demonstrate. The astute quote from T.S. Eliot (immature poets imitate, mature poets steal) also applies to musicians. The artists who try to imitate Dylan’s heartache (Lloyd Cole, My Morning Jacket, to name but two of the better-known) are whining, ruin a work of art. The colleagues who understand that they should not try to imitate Dylan, swing in the other direction, concentrate on the beauty of the composition and deliver a shiny, but flat, emotionless interpretation. Mary Lee’s Corvette, for example (on her otherwise beautiful integral live performance of Blood On The Tracks, 2002), and even the grandmaster of the Dylan interpreters, the Texan Jimmy LaFave, is brilliant, but sterile (Austin Skyline, 1992).

The most enjoyable are the artists who only cherry pick the best bits, and stay far away from the pangs of love. The collective Zita Swoon from Antwerp (who already produced a attractive “Series Of Dreams”) performs live a dreamy, hushed version which puts emphasis on the music, not on the lyrics. This is even more true for Dave’s True Story, a jazz/pop band from New York that chooses a Steely Dan approach on their fascinating tribute project Simple Twist Of Fate (2005), an album with seven jazzy Dylancovers. Only “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” really does not fit in with the languid, nonchalant jazz arrangement, but the combo does produce, by far, the most beautiful cover of “You’re A Big Girl Now”. Two of them, even – the radio edit is slightly more compelling. Opening with a rustling cymbal – I’m back in the rain.

What else is on the site

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ Dylan compositions reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews

Lovely article, well done. Beautiful song which has really stood the test of time.

Great piece. Lucky break I ran across it.

Great article, thanks again, Jochen.

I think I come down on the side of the NYC version, for this song. He doubles up the moaning part in each verse, but also, his vocal is intense. When he sings, “I’m going out of my mind”, he actually sounds like he’s gone out of his mind already. It’s very painful, and beautifully sung. In the Minnesota version of this song (and If You See Her), I kinda feel the intensity is gone, and he’s “faking” it a little, if such heresy may be uttered.

In the NYC version, I also think he sings “like a cork screwed up my heart”, which – as you say – is an image which resonates…

Thanks gentlemen, I do appreciate your kind words.

I think I agree, Kieran. I really, really love take 2, remake, the version with that heartbreaking organ by Paul Griffin and the tear-jerking steel guitar from Buddy Cage.

As for your heresy: it reminds me of the eyewitness account of Glenn Berger, the then nineteen-year old assistant engineer in New York, in his book Never Say No To A Rock Star (2016):

The whole studio throbbed, the big box with the copper roof about to blow off with all the pain, the anger, the truth. The tape machine flew in circles, the tape whirred, it seemed faster and faster than the thirty inches per second that I knew it travelled, the red lights seemed brighter, the needles pushed into the red zone, Ramone’s shoulders tensed, his total focus on what was in his hands, temperature rising, I started to hallucinate, the red lights turned to blood, the blood ran on to the tape machine, blood on the tracks …

The plaintive moan of his harmonica, then the final, clangorous chord.

Then silence.

The song over. No one speaks when a take is done.

We sat and waited. Just the sound of the tape machine still whirring: flap, flap, flap. Now the needles still. The blood back to lights glowing, telling us it was all down on tape. We waited.

Dylan turned to us in the control room and snarled sarcastically, “Was that since-e-e-re enough?”

Young Glenn is rather upset: “He’d murdered his musicians with the aplomb of a psychopath; he recorded his album sloppily in a day and then did it again two times more, and now this? Was it fucking sincere enough? I was ready to puke.”

In short, I guess you’re not the only one who suspects faking, haha.

Groeten uit Utrecht,

Jochen

Peter’s Ladder Of Success Rule:

Sincerity is the secret of success.

Once you can fake that, you are on your way.

That’s a great, cynical and probably truthful quote, Larry. Groucho, would be my guess.

The live versions of this song from the latter part of the 1978 tour create quite a different impression from the album and Rolling Thunder tour versions. It turns into a restless, pacing, bluesy, sexualised performance, more like the later Can’t Wait than the earlier nostalgia ridden versions of Big Girl Now. Almost predatory. Highly recommended, if you can find them.

Thanks again Jochen

Hi Jochen,

That’s a great story by Berger. I heard great things about his book – it’s on the list! I actually came across the NYC version before I ever heard BOTT, my uncle was a bootlegger and he gave me a cassette called Passed Over & Rolling Thunder when I was young. So maybe I’m biased towards the bootleg, but when I finally got BOTT, I was appalled, to put it nicely. Too slick and mawkish. That song, anyway. I think the Minnesota version of Tangled works very well, and maybe Lily, Rosemary needed a bit of pace.

KIWIPOET: I’m familiar with the version of You’re a Big Girl Now (1978) from the Rundown rehearsals boot, and it’s a whole nother song with that great Street-Legal band! Love it!

Lots of interesting covers. On the raw end I gotta love Lambchop’s https://youtu.be/G3pmv1OUdPE

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/781/Youre-a-Big-Girl-Now

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan’s Music Box.