by Filip Łobodziński

“Artists are being objectified, taken over and thus, ridiculed by their audience who don’t understand their work anymore or does so only in a twisted, limited manner. The only way to escape this slavery and regain one’s freedom is to become a wave, something intangible and elusive.”

Prompted by Aaron Galbraith and Tony Attwood, I promised to explain the meaning behind the song written by Polish singer-songwriter Jacek Kaczmarski in “The Dylan Nobody Knows”. If you who have already listened to the song, sometimes titled Epitafium dla Dylana or Epitafium dla Boba Dylana [Epitaph to (Bob) Dylan], you have perhaps some ideas as to what it is all about, yet you won’t know the story behind without yours truly, your Polish connection.

Prompted by Aaron Galbraith and Tony Attwood, I promised to explain the meaning behind the song written by Polish singer-songwriter Jacek Kaczmarski in “The Dylan Nobody Knows”. If you who have already listened to the song, sometimes titled Epitafium dla Dylana or Epitafium dla Boba Dylana [Epitaph to (Bob) Dylan], you have perhaps some ideas as to what it is all about, yet you won’t know the story behind without yours truly, your Polish connection.

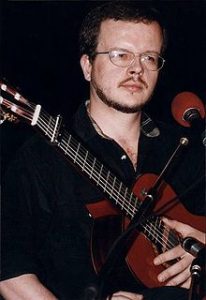

First things first – who is Jacek Kaczmarski? I say “who is” in spite of him having sadly passed away sixteen years ago, aged only 47 – because he remains one of the most inspiring and important artists, having written around 600 extraordinarily crafted and very intelligent and deep songs or poems.

He’s been called “bard”, a word which is nowadays used to denominate songwriters who perform their own poetic and meaningful songs, mainly solo. Thus, the main bards in modern history are the likes of Vladimir Vyssotsky, Bulat Okudzhava, Alexandr Galich, Jacques Brel, Georges Brassens, Léo Ferré, Georges Moustaki, Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Karel Kryl (of Czechia) and quite a few more. Probably each community has its own lesser-scale bards too.

Kaczmarski’s main sources of inspiration were Russian bards and French poets of “chanson”. His first adaptations and/or translations were songs by Georges Brassens and Vladimir Vyssotsky. And though he translated songs from English too (namely, It Ain’t Me, Babe and A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall by Dylan, What Did You Learn in School Today? by Tom Paxton, Hank and Joe and Me by Johnny Cash or Dennis O’Reilly from Australian folk tradition), he remained faithful to the Russian school of high-register expression and to the French verse craft. His songs are perfectly organized, have inventive rhymes, and, true to the folk tradition, they more often than not have no choruses.

What is much more important, his songs are always deep and thought-provoking. As you may see on his Wiki entry, “His deep knowledge of not only his nation’s history but also of classical literature gave his songs a particularly deep and multi-layered resonance”.

What does that mean? He based his songs on historic events and figures, on literary contexts and on great paintings, introducing the listeners to the content of the work/event that gave him inspiration and then leading to sometimes obvious, sometimes surprising, and always very clever conclusions and punchlines that could be taken for morals or mementoes. His audience always waited for the concluding stanzas because they always brought some instructive message. Sometimes hilarious but generally bitter.

On the Wikipedia page you’ll learn Jacek Kaczmarski was the voice of Solidarity union. Well, not quite. I met Jacek when I started my University studies (Spanish literature and language) in Warsaw in 1978, I was 19 and he 21. He was already a legend because of his songs that were very anti-Communist or anti-regime while being very poetic and strong (their often allegoric nature saved him from being openly arrested or persecuted). And he sang them with conviction and power.

On our first meeting we, my friends and I, introduced Jacek to the songs of another great singing poet, Lluís Llach of Catalonia. We played him a live album by Llach Barcelona Gener de 1976, recorded in Barcelona three months after Franco’s death, when Llach for the first time could sing his songs to Catalan audience without being censored or totally forbidden.

The crowd’s reactions are what makes the album very special. Jacek was especially struck by one song, L’estaca. We translated this song literally for him so that he could know what it was about. Three weeks later, in January 1979, Jacek came out with his own song written to the Llach’s tune, it was called Ballada o pieśni (Ballad of a Song). It is important because it was probably the first example of Jacek’s deep obsession about the position of an artist versus her/his followers. The song Bob Dylan is another example of this motif.

The Ballad of a Song soon became known as Mury (Walls) and turned into an informal anthem of people protesting against the regime.

When the Solidarity movement emerged it soon adopted the song as their own – in spite of the true meaning of the song. Mury tell the story of a singer adored by crowds, singing about the necessity to put down the walls of the prison the society is confined in. The crowd then takes the song to the street and instead of building a new order people only destroy, chanting “They’re with us! They’re against us! Those that are alone are our worst enemies!” while the singer remains alone too, seeing the walls rise back. (An echo perhaps of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies). This punchline was completely overlooked by the Solidarity members. You can read more on Kaczmarski here

Now, in November 1981 Jacek went to France to organize a tour for himself and his two musical partners – and was surprised there by the martial law imposed on December 13. He became an émigré for the next eight years, living in Paris and Munich and touring Polish communities all over Western Europe as well as North America and Australia.

He wrote many songs, recorded them partly as thoroughly sequenced song cycles, partly as just free-standing items. Some of these recordings were made during private home parties, they were of course much looser, and then Jacek would introduce some lighter or funnier songs. He drank a lot so he too was sometimes very loosened while performing them – but never to the extent of not being able to sing and play them properly.

And sometime in 1987 he began including a song called Bob Dylan in those private performances. He always used to emcee his songs with stories behind. And this particular song was then preceded by the following story.

It was just after the infamous Live Aid Philadelphia concert where Bob Dylan couldn’t hear himself nor his Rolling Stone mates. The performance was largely criticised for being either done by a booze/drug infused artist or an epitaph to a legend who’d forgotten about his former relevance. Jacek Kaczmarski told his audience he couldn’t believe his idol could have fallen so low. “He sang wise words but he didn’t know or understand their wisdom anymore”.

And then Jacek reported that he met Bob Dylan in person. It was in Australia they both toured at the time. Jacek said he’d been thrilled to meet one of his idols – and then Bob Dylan appeared “completely stoned or drunk or both”, saying only “hi” and not much more.

And so Jacek decided to write a song, an epitaph (he initially called it Epitafium dla Dylana, Epitaph for Dylan) to his own hero who had succumbed to addictions and lost all his power and wit. And, he added, “His guitar in Philadelphia was out of tune so I put my guitar out of tune too”.

Both previously and afterwards, Jacek wrote several songs with Epitafium dla (epitaph to) in their titles, dedicating them mainly to great deceased figures such as Vladimir Vyssotsky, Polish poet Bruno Jasieński, priest Jerzy Popiełuszko assassinated by the Communists, or Til Eulenspiegel. So it was natural that his Dylan song got the Epitafium title. Yet, now its proper title is just Bob Dylan. On a cassette recording from 1988 it’s called Dylan pastisz (Dylan, a pastiche). Officially, he registered it as Bob Dylan, possibly he prefered not to suggest he’d wanted Dylan to die.

Following are the original lyrics and then its verbatim translation appears below.

Ocean w nas śpi

I horyzont z nas drwi

Płytka fala fałszywie się mieni

A prawdziwy jest rejs

Do nieznanych ci miejsc

Kiedy płyniesz na przekór przestrzeni

I na tej z wielu dróg

Po co ci para nóg

I tak dotrzesz na pewno do końca

Niepotrzebny ci wzrok

Żeby wyczuć swój krok

I nie musisz wciąż radzić się słońca

Wielbicieli i sług

Tłum ci zawisł u nóg

To wolności twej chciwi strażnicy

Zaprowadzisz ich tam

Gdzie powinieneś być sam

Z nimi żadnej nie przejdziesz granicy

Zlekceważą twój głos

Którym wróżysz im los

Od jakiego ich nic nie wyzwoli

Bo zabije ich las

Rąk co klaszczą na czas

W marsza rytm co śmierć niosąc nie boli

Patrz jak piją i żrą

Twoją żywią się krwią

I żonglują słowami twych pieśni

Lecz nic nie śni im się

A najlepiej wiesz że

Nie istnieje wszak to co się nie śni.

By przy śmierci twej być

Płakać śmiać się i drwić

To jedyny cel twojej eskorty

Oddaj komuś rząd dusz

I na własny szlak rusz

Tam gdzie żadne nie zdarzą się porty

Mówić będą żeś zbiegł

Ale wyjdą na brzeg

I zdradzieckie ci lampy zapalą

Ale ty patrząc w dal

Płynąć będziesz wśród fal

Aż sam wreszcie staniesz się falą…

And this is a rough translation which, in spite of all its roughness, captures the song’s inner sense:

The ocean sleeps within us

and the horizon makes fools of us

a shallow wave shimmers falsely

while a real cruise is

when you go to unknown places

sailing despite space

On this way, one among many

you won’t need your pair of legs

you’ll get to the end anyway

sight is not indispensable

to sense your own pace

and you don’t have to seek the sun’s permanent guidance

The admirers and servants

hang at your feet in vast numbers

greedy guardians of your freedom they are

you’ll lead them

where you should be alone

with them, there’s no frontier you shall pass

They’ll leave unheeded your voice

with which you bode them their fate

they won’t be able to free themselves of

because the’ll be killed by a forest

of hands clapping in time

to a march which brings death yet is painless

See them drink and raven

they feed on your blood

and juggle with the lyrics of your songs

but they dream no dreams at all

and you know better than anyone

that what can’t be dreamt of doesn’t exist

To witness your death

to weep, laugh and sneer –

that’s the only aim of your escort

let others rule the souls and minds

and take your own route

where no ports would happen

They’ll say you’ve escaped

but they’ll stand on the shore

and light treacherous lamps for you

yet you, looking far and away

will sail among the waves

until you become a wave yourself

As you may see now, the introduction Jacek Kaczmarski used to precede the song in the eighties suggested a much more acerbic tone. It’s as if Jacek wanted to write a diatribe, an epitaph to his own illusion – but wrote a bitter reflexion on an artist’s doom and on her/his followers’ dumb possessiveness. In fact, being a huge Bob Dylan fan who even likes his Live Aid performance for some reason, I expected something much more hostile.

Jacek wrote another piece on the artist’s solitude and isolation from her/his fans. The fans, the crowd, the multitude – they hear their idols’ words, they even repeat them and learn by heart, but they don’t listen to them nor understand them. Jacek Kaczmarski was never a crowd-appealing singer – and the same goes for Bob Dylan, John Coltrane, Björk, Nick Cave, you name it. He wrote a song about himself, actually, only giving it a title that suggested another protagonist. And when he reintroduced Bob Dylan into his repertoire in the late 1990s, it sounded different. He was no longer a hero who used to sing protest songs, he had matured and saw things from a much more personal perspective, a perspective of a so-called sage. He told the same anecdotes about Dylan before performing the song but he didn’t mean it as a diatribe anymore. Thus, I think it is a kind of paean, only in frigid disguise.

The tune echoes When the Ship Comes In, of course, but it’s Jacek Kaczmarski’s tune, only inspired by Dylan’s song. The structure is also close to the Ship pattern or, should I say, to many English poems with an ‘aacbbc’ rhyming pattern. But the landscape/inner world of the song is pure Kaczmarski. For Jacek, ocean, wave, horizon and space are key words denoting an artist’s life. And the main idea is that artists are being objectified, taken over and thus, ridiculed by their audience who don’t understand their work anymore or does so only in a twisted, limited manner. The only way to escape this slavery and regain one’s freedom is to become a wave, something intangible and elusive.

One more thing which somehow makes me not like the song as much as it probably deserves. The way Jacek sings it robs it of its meaning and power. He starts with a Dylan impersonation, he tries to prolong some vowels the way Dylan often does, he alters the melody and does some melodic declamation at times. If it was meant as a parody it missed the point. Listeners were pleased to recognize the “Dylan” voice and would laugh because for Polish ears Dylan’s singing is generally hard to like (a matter of cultural DNA), we Poles prefer Cohen or Springsteen (not me, I’m totally on Dylan’s side). Now, this irreverence makes people lose the real message. If Kaczmarski sang it without trying to mimic Dylan’s voice the effect would be much stronger.

It’s a bit as if Jacek Kaczmarski sang wise words but no longer understood their wisdom. Which is not true but the appearances suggest otherwise. Jacek’s own version makes me think its author did not fully believe the song.

You might also enjoy, by the same author

- Like a Polish Stone: the issues of translating Bob Dylan into a foreign language.

- The consequences of sequences in Bob Dylan’s writing of song

- Studious Dylan in the Studio

- Like a Polish wanderer: the work of translating Bob Dylan

- The art of performing Dylan in Polish

What else is on the site?

We have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with over 3400 active members. (Try imagining a place where it is always safe and warm). Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to all the 602 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found on the A to Z page.

If you are interested in Dylan’s work from a particular year or era, your best place to start is Bob Dylan year by year.

On the other hand if you would like to write for this website, or indeed have an idea for a series of articles that the regular writers might want to have a go at, please do drop a line with details of your idea, or if you prefer, a whole article to Tony@schools.co.uk

And please do note our friends at The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, plus links back to our reviews (which we do appreciate).

Hi Filip

This is a fantastic article. I learned so much about Jacek Kaczmarski. I wasn’t aware of any of this. I’m so glad Tony thought of the idea for the series which led me to suggest this song for the first article…which led to this piece. This is what i love about Untold Dylan!

Me proud. Thnak you, Aaron.