This article is part of a series that tells the story of the artwork on each of Bob Dylan’s albums. A list of all the previous articles in the series is given at the end of this piece, and is stored permanently on the Album Artwork page shoudl you lose track of this article.

The story of the art work on Bringing it All Back Home

by Patrick Roefflaer

- Released: March 22, 1965

- Photographer: Daniel Kramer

- Liner Notes: Bob Dylan

- Art-director: John Berg

In early 1964, Daniel Kramer was a photographer from Brooklyn trying to launch a freelance career. He had come to photography early, aged 14, and later fell into a job working as an assistant at the studio of the fashion photographer Allan Arbus.

“His wife, Diane Arbus, also did her darkroom work there,” he explained. “It turned out to be more than just a job. From Allan I learned to manage a studio, work with models, and run the business – and from Diane, I learned to open my eyes a bit wider, to think about my pictures in new ways.”

Now turning 33, he had recently opened his own studio in New York City. As a freelance photographer, he was on the lookout for “interesting material”, when Bob Dylan performing on television caught his attention. It was February 25th, just two weeks after The Beatles had made their first American television appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show.

That evening on the Steve Allen Show, there were no girls screaming for mop-topped guys in Edwardian suits, there was just a thin folk singer with a guitar, talking uneasily with the host. But his attitude changed completely when he started singing.

That evening on the Steve Allen Show, there were no girls screaming for mop-topped guys in Edwardian suits, there was just a thin folk singer with a guitar, talking uneasily with the host. But his attitude changed completely when he started singing.

“I couldn’t believe what I was hearing,” Kramer vividly remembered (in May 2016).

“He was singing a song called ‘The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll’ – a long piece about a wanton murder, and about the pitiful way the justice system handled it.

So here was this young guy with just his guitar, and he was saying these powerful things that you have to be brave to say.“

“People didn’t sing about those things easily on TV,” Kramer explained on another occasion. “People just didn’t do it. It was too scary and too dangerous. It was an era in which a President was shot. A great religious leader was shot. Other important movers and shakers in our society were shot.

We were a shooting gallery here in the ’60s, and here was this guy who looked like he was in his early 20s, singing about something very critical and very touchy. Well, that got my attention.”

Kramer is hoping h e could add this fascinating singer to his portfolio. So he reaches out to Bob Dylan’s agency. “I began sending notes, and making calls, to the office of Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman, asking for a one-hour session,” Kramer recalled. “The office always said no.”

e could add this fascinating singer to his portfolio. So he reaches out to Bob Dylan’s agency. “I began sending notes, and making calls, to the office of Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman, asking for a one-hour session,” Kramer recalled. “The office always said no.”

For six months, he got nowhere. But he kept trying, and a breakthrough happened one day after business hours, when a call was picked up by Grossman himself instead of a secretary. “He just said, ‘OK, come up to Woodstock next Thursday’,” Kramer remembers.

It was on August 27, 1964, that the photographer made the long drive to the sleepy town of Woodstock, two hours north from New York City. But when he got to the house, Dylan wasn’t even there. The 23-year-old musician showed up about an hour and a half later on his motorcycle and greeted Kramer with a gentle, “almost nonexistent” handshake.

To Dylan’s question what kind of photos he wanted to take, Kramer replied, “Oh, do what you want to do”, whereupon Dylan took him to a movie room to view recently recorded film footage. In the dark, the photographer, of course, couldn’t do anything at all.

Fortunately, he saw the humour in it. “Woodstock was like the testing day for him and me. He gave me a hard time. It was like a courtship. I guess I passed the test.”

Once Dylan let down his guard, he made it clear that he wouldn’t be sitting for a portrait. “He said, ‘You can do anything you want, you can shoot anything you want the whole day, whatever you want — as long as I don’t have to sit still in the chair,’ ” Kramer said. “He’s always in motion, even when he’s sitting.”

So Kram er snapped away while Bob read the paper, climbed a tree, played chess with his road manager Victor Maymudes, hung out with Sally Grossman (Albert’s wife) and his own wife-to-be, Sara Lownds. At the end of the day, the one-hour photo session appeared to be stretched to five hours. When it was time for Kramer to eventually leave, he got a much warmer handshake from Dylan. “Like I suspected, he just was cautious,” Kramer said. “And I guess you have to be in this business.”

er snapped away while Bob read the paper, climbed a tree, played chess with his road manager Victor Maymudes, hung out with Sally Grossman (Albert’s wife) and his own wife-to-be, Sara Lownds. At the end of the day, the one-hour photo session appeared to be stretched to five hours. When it was time for Kramer to eventually leave, he got a much warmer handshake from Dylan. “Like I suspected, he just was cautious,” Kramer said. “And I guess you have to be in this business.”

About a month later, Kramer met Dylan again at Grossman’s office, where he showed off his photos from the shoot. Dylan must have liked what he saw, because he said “I’m going to play in Philadelphia next week. Would you like to go?”

If you want to be a good photographer, you need three things: you need a camera, a phone and you need to say “yes”. I had never heard Dylan play live.

So I drove with [Bob Dylan and Victor Maymudes] in their station wagon to Philadelphia and we got to know each other a little more. He wanted to know about the work I had done with Salvador Dalí. I was an assistant to a photographer who worked with Dalí a lot. Dylan and I were discussing Dalí’s ability to be a showman. He’s the opposite of Dylan. Dalí made a whole business out of “here I am.”

That trip w as when he really got to know Dylan.

as when he really got to know Dylan.

In January 1965, Kramer is a privileged witness in Columbia’s Recording Studio to see Bob plug in and “go electric”, recording the songs for his next album, Bringing it All Back Home. So, he seems a natural choice to shoot the photo for that album cover.

“I had never done an album cover”, explained a then 88 year old Daniel Kramer in November 2019, at a show in the New York photo lab Duggal Visual Solutions, “because I was just starting with professional photography, at the same time of shooting Bob. I was excited to do the album cover, so I went to the art-director at Columbia Records and I said, “Bob would like me to do the album cover. How would you like me to handle it?”

And he said, ‘You can’t do it. […] Bob’s a superstar. I need a superstar photographer to do it.’

“That made sense, as I was just starting.”

Later that day, he has an appointment with Bob and his manager to have lunch. When Grossman informs about the cover, Kramer explains the situation. “So Albert stands up – he was an impressive person. He took me by the wrist. With his other hand he grabbed Bob’s wrist, pulled us both up and on our feet and he went to the elevator, pulling the two of us. We got up to the art-director’s office… It was ugly. It was very, very ugly. But when we left I was going to shoot the album cover.”

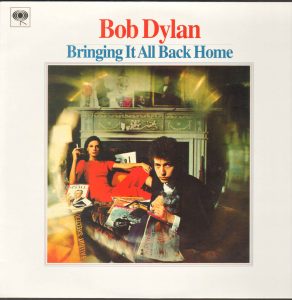

Kramer wanted to present Bob Dylan at the centre of the universe, the chaos surrounding him, but he knows what’s going on. “Bob Dylan not only sees the world around him changing but also understands it, while it is blurry for everyone else.”

To accomplish this he thought of something he had developed for a fashion shoot. In 2019 Kramer explained the technique: “I remembered a picture that Richard Avedon made – that was a star photographer (laughs). What he did was a picture of Brigitte Bardot. He photographed her with her hair loose and then put his hand over the middle of the picture while the thing was closed, so that she wouldn’t get blurred. And he then moved the easel like this (makes a movement with his hand from side to side, without moving his wrist) and he made blurriness in her hair, like waves in the ocean.”

To accomplish this he thought of something he had developed for a fashion shoot. In 2019 Kramer explained the technique: “I remembered a picture that Richard Avedon made – that was a star photographer (laughs). What he did was a picture of Brigitte Bardot. He photographed her with her hair loose and then put his hand over the middle of the picture while the thing was closed, so that she wouldn’t get blurred. And he then moved the easel like this (makes a movement with his hand from side to side, without moving his wrist) and he made blurriness in her hair, like waves in the ocean.”

“So, I build a construction for my view camera – the one where you put a black cloth over your head – and then I put the glass in front of the lens on a 45 degree angle, so it won’t make any reflection back. I got black paper and scissors. I focused my picture […], I would take one picture with speed light and get everything. Then I would go to Tungsten light, so I could make a one-second exposure, while I turned the back of the camera. But I had to put a piece of black paper on the glass on the 45-degree angle.”

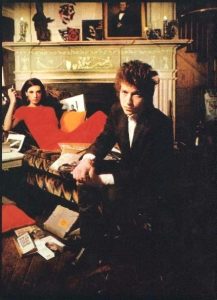

When the record company agreed to let Daniel Kramer do the shoot, they had one requirement: like on the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, there has to be a girl in the photo. However, Bob wanted to keep his girlfriend out of the picture – especially since he is also seeing Joan Baez a lot. Sally Grossman happened to be in the office when this is being discussed and Dylan suggested she’d do it.

An arrangement is made to shoot at the home of Sally and Albert in Bearsville, near Woodstock. The choice for the setting is made for the former kitchen of the house: in front of the fireplace, around a chaise longue (a wedding gift from Mary Travers, of Peter, Paul and Mary).

Before the singer arrives, Kramer makes a polaroid, to explain the idea to Bob. “He immediately understood,” says the photographer. They need things ‘to move’, so Daniel suggests Bob get some favourite objects. “He chose some things, so did I and perhaps Sally brought some too. It became a bit busy – too made up – so we got rid of some.”

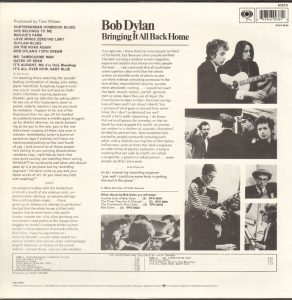

Besides books and magazines, there are a lot of albums in the picture: The Impressions, Robert Johnson, Lotte Lenya, Ravi Shankar and Eric Von Schmidt. What’s remarkable is that Dylan’s last album, Another Side of Bob Dylan, is way at the back: in the fireplace, as if he says: this is far behind me.

At the front, there’s an EP by the French singer Françoise Hardy: ‘Tous les garçons et les filles’. This is the second time Dylan honours Française: one of the poems at the back of Another Side was dedicated to her. The Extended Play is only visible in outtakes of the shoot.

You can find more details about the objects here: https://nobodysingsdylanlikedylan.com/bringing-it-all-back-home-uncovered

“I made 10 exposures,” Kramer explained. “That [cover shot] was the only time all three subjects were looking at the lens.” That was Bob, Sally and a cat. The cat looks scared, Sally looks bored and Dylan looks like he’s discovered that scowl. According to biographer Robert Shelton, the cat is called Rolling Stone (No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan – Beech Tree Books, 1986), but other sources think his name was Lord Growing.

“It was a v ery important cover for Bob,” Kramer knows. “And the reason is the first four albums he did, he’s a folk singer. He’s in folk singer clothes, he looks, you know, ‘Oh, woe is me.’

ery important cover for Bob,” Kramer knows. “And the reason is the first four albums he did, he’s a folk singer. He’s in folk singer clothes, he looks, you know, ‘Oh, woe is me.’

On Bringing It All Back Home, he’s a prince in his blazer and his beautiful cufflinks, sitting with this beautiful cat and a ravishingly beautiful woman behind him in a red dress. It was a change. Everything was changing.”

The message is as good as a middle finger presented to the people nagging about authenticity: bye-bye folkies, here’s a rock star!

John Berg

The pictures Daniel Kramer made were rectangular, but the art-director John Berg cut it at the bottom of the sofa because he felt it worked better as a square. He added a white border, the name of the performer in red and the title in blue. Contrary to the habits of the record company, the titles of the songs were not mentioned on the front – the first time Columbia allowed this.

On the back of the album’s sleeve are liner notes, written by Bob Dylan, plus a selection of six black and white photographs from Kramer’s portfolio.

- Bob with Joan Baez (probably taken at the Convention Center, Philadelphia, on March 5th 1965);

- Peter Yarrow taking with some policemen (on 5th Avenue);

- Allen Ginsberg (in high hat) backstage at the Dylan concert in the McCarter Theater in Princeton, New Jersey, September 1964;

- Dylan at a recording session for Bringing It All Back Home (January 1965);

- Underground film maker Barbara Rubin (who introduced Dylan to Andy Warhol) massaging Bob’s head backstage at the McCarter Theater;

- Dylan (in high hat) leaving the Town Hall in Philadelphia, after the concert on October 25th 1964.

Photographer Daniel Kramer and art-director John Berg are nominated for a Grammy Award in the category Grammy Award for Best Recording Package 1966, but the honour goes to Robert M. Jones and Ken Whitmore, for Jazz Suite on the Mass Texts van Paul Horn.

Post scripts

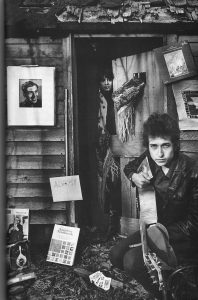

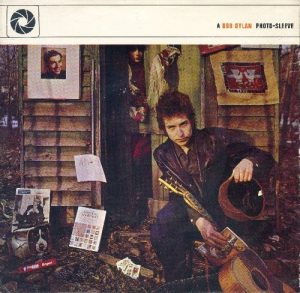

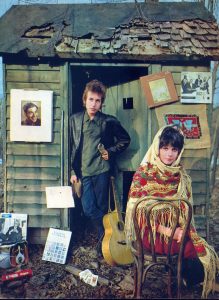

Inspi red by the success of the album sleeve, Kramer repeats the shoot a month later, for the cover of Dylan’s experimental book Tarantula.

red by the success of the album sleeve, Kramer repeats the shoot a month later, for the cover of Dylan’s experimental book Tarantula.

Once more the location is in Woodstock, but this time it’s in the garden of Peter Yarrow’s mother’s house.

On March 15, 1965 they gather objects around Bob, in front of a little shed. This time he’s accompanied by Sara.

It’s finally decided not to use this photograph ‘Unfortunately, we did it too good,’ Kramer reminisces in his book Bob Dylan by Daniel Kramer (Citadel Books, 1967)

‘The photo resembled too much the one on Bringing It All Back Home.’

The title of the album is probably a reference to the return to the musical roots of his youth and at the same time also the shift of the focus of new songs from universal concerns to more personal conflicts.

The title of the album is probably a reference to the return to the musical roots of his youth and at the same time also the shift of the focus of new songs from universal concerns to more personal conflicts.

On the other hand, the title can also be interpreted as an answer to the British Invasion in the wake of The Beatles. The young Brits brought rock ‘n’ roll back to the American charts.

Dylan took up the gauntlet, setting a new  standard for the genre and thus reclaiming it for the country of origin.

standard for the genre and thus reclaiming it for the country of origin.

The latter interpretation may have been the basis for renaming the album in some European countries after the first single from the album: Subterranean Homesick Blues.

That title was even kept for a long time during the transition from LP to CD.

Other articles from this series

- The untold story of the artwork on Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- The Sleeve Art of Bob Dylan’s album: “Bob Dylan”

- The Sleeve Art of Bob Dylan’s Album: Slow Train Coming

- The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan – the untold story of the artwork of the album

- Times they are a changin’: the album artwork

- The art work on Bob Dylan’s albums: The Basement Tapes

- The source of the artwork of “Another side of Bob Dylan”

- The art work on Bob Dylan’s “Infidels”: what’s in a name?

- The art work of Nashville Skyline

- Absolute Exclusive: Empire Burlesque and Biograph artwork

- The artwork to Knocked Out Loaded

- The Art Work of the Traveling Wilburys Vol 1 (guest visitor, Michael Palin)

What else is on the site?

We have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with over 3600 active members. (Try imagining a place where it is always safe and warm). Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to all the 603 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found on the A to Z page.

If you are interested in Dylan’s work from a particular year or era, your best place to start is Bob Dylan year by year.

On the other hand if you would like to write for this website, or indeed have an idea for a series of articles that the regular writers might want to have a go at, please do drop a line with details of your idea, or if you prefer, a whole article to Tony@schools.co.uk

And please do note our friends at The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, plus links back to our reviews (which we do appreciate).

Where is that house where the Bringing It All Back Home cover was taken? The first picture, if recent, is almost completely untouched from the day the cover was taken!

Firstly, I just want to remark that, after having been directed here by a reader’s post on Sally Grossman’s obituary (may she rest in peace), I am simply giddy about this ‘new’ discovery; namely, this stupendous website. Thank you!!

As to Maxfield’s query, the photo shoot was taken at Albert and Sally Grossman’s home in upsate New York – Bearsville to be exact. (This info was taken from Sally’s obit in the NY Times.)

Juan, thanks for your kind comment. It is really appreciated.

Tony Attwood

Also the Red, White and Blue Cover