- Love Minus Zero/No Limit part I: Rose of England

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit part II : A Song Of Ice And Fire

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit part III: I love you, but you’re strange

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit part IV: The Order of the Whirling Dervishes

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit part V: When a sighing begins in the violins

- Love minus zero/No limit part VI: Fair is foul

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit part VII: Your silent mystery

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit part VIII: A Study Of Provincial Life

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit part IX: Where little girls say pardon

by Jochen Markhorst

X The pallid bust of Pallas

My love she’s like some raven At my window with a broken wing

The nineteenth-century German poet Heinrich Heine is one of its godfathers, of the finale that turns all the previous upside down – die ironische Pointe, the ironic punchline. Humorous poems, say Robert W. Service’s “The Cremation Of Sam McGee”, have the surprising twist almost by definition, of course – a punchline is simply a strong weapon – and murder ballads too often only reveal their bloody intent, let the blood spurt, not until the last line.

The nineteenth-century German poet Heinrich Heine is one of its godfathers, of the finale that turns all the previous upside down – die ironische Pointe, the ironic punchline. Humorous poems, say Robert W. Service’s “The Cremation Of Sam McGee”, have the surprising twist almost by definition, of course – a punchline is simply a strong weapon – and murder ballads too often only reveal their bloody intent, let the blood spurt, not until the last line.

In his mercurial years, Dylan develops a soft spot for a variant of the punchline and the plot twist. In longer songs such as “Desolation Row”, “Tombstone Blues” and “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”, the songwriter creates seemingly unrelated tableaux which are offered a red thread in the last stanza – usually tilting the gist. Sometimes by suddenly, out of nowhere, introducing a “you”, sometimes by unexpectedly providing a framework that might all of a sudden connect the preceding, seemingly unrelated images, tableaux and scenes. A letter in “Desolation Row”, for example, and alcohol and harder stuff in “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”.

“Love Minus Zero” offers a different kind of twist. My love she’s like some raven at my window with a broken wing surprises mainly by its unmistakable negative connotation. The my love as we have come to know her in the previous verses is a soft speaking, flowery laughing, emotionally stable, perhaps detached but still desirable creature. Granted, maybe a tad weird, but predominant is: the first person seems to like her very much.

Up to this final line, that is. When enamoured protagonists compare a loved one to fowl, it usually is a dove, a nightingale, sometimes a bluebird or even a chick, but never a raven. Hair colour, yes: “Her raven hair shining,” Jim Reeves sings about a Mexican beauty (“Drinking Tequila”), the adorable Wildwood Flower has pale cheeks but raven black hair (The Carter Family) and Van Morrison is literally a little creepy in “Spanish Rose”:

In slumber you did sleep, The window I did creep And touch your raven hair and sang that song Again to you

Well alright, there is one song in which a raven actually gets a loving mention: “Rockin’ Robin”, Bobby Day’s greatest hit from 1958;

Well, the pretty little raven at the bird bandstand Taught him how to do the bop and it was grand They started going steady and bless my soul He out-bopped the buzzard and the oriole

… without too much meaningful depth, of course. The song is above all a declaration of love to the irresistible singing of a rockin’ robin, and how the whole aviary, from the buzzard and the crow to the oriole and the owl, and indeed the raven too, is delighted with this remarkable robin.

But comparing a lady to a raven is hardly a compliment. Ravens, through all ages and in every art form, are dark and sinister, symbolising death and the fleeting of life, are hellish, or at least devilish birds. Dylan knows that too. Dylan has, for example, undoubtedly put Judy Collins #3 (1963) on his turntable more than once. That’s the record that opens with “Anathea”, which Dylan will transform into “Seven Curses”, with “Deportee”, “The Bells Of Rhymney”, “Turn! Turn! Turn!” and “Come Away Melinda”, with songs that Dylan will add to his own repertoire or that echo paraphrased in his own songs. And above all, the record which the young Dylan will have heard with glowing ears because of Collins’ covers of his own “Farewell” and “Masters Of War”, with which Judy Blue Eyes propels Dylan to the top of Great Songwriters.

Amongst all that beauty, Collins also sings Ewan MacColl’s “The Dove”, in which the dove depicts a desirable young lass keen on marrying, contrasting sharply with the raven:

Come all you young fellows take warning by me Don't go for a soldier, don't join no army For the dove she will leave you, the raven will come And death will come marching at the beat of a drum

Of course, Dylan is familiar with the ominous symbolism of the black-feathered creep way before he hears “The Dove”. Poe’s unrelenting masterpiece “The Raven” has been in the Top 10 of the canon for over a century, and has prefigured any artist’s association with death since. In fact, Poe’s “The Raven” is so inescapable that many analysts classify the mere mention of a raven in “Love Minus Zero” as a “Poe reference”. Or at least: many analysts parrot each other and point to Edgar Allan.

This is not elaborated on anywhere. Hardly surprising; in terms of content, there is no common ground with Dylan’s song anyway. It makes the label “Poe reference” rather thin – with equal force one could argue that the mere mention of “silence” in line 1 is a reference to Simon & Garfunkel, or to John Cage’s 4’33”-, and catalogue roses as wink to Shakespeare, or Rilke, or Blake. Which is nonsense, obviously.

Stylistically, at most, there are some superficial similarities. Poe’s breath-taking masterpiece demonstrates a similar mastery of rhyme and rhythm as Dylan’s best works, and Dylan shares with Poe a love of internal rhyme, assonance and alliteration – the stylistic devices that Poe applies in extremis in “The Raven”. Leading to irresistible, meandering gems like

Eagerly I wished the morrow;—vainly I had sought to borrow From my books surcease of sorrow—sorrow for the lost Lenore— For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore— Nameless here for evermore.

… wordy arabesques like those we know from songs like “To Ramona” and “Where Are You Tonight?” and, to some extent, also from “Love Minus Zero”. What the Poe fans still miss is the presumably coincidental, but nevertheless funny similarity: this one line with the supposed Poe reference, My love she’s like some raven at my window with a broken wing, is the only song line from “Love Minus Zero” that is, like The Raven‘s poem lines, an octameter; eight feet, each foot having one stressed and one unstressed syllable (Poe trochaic, Dylan iambic).

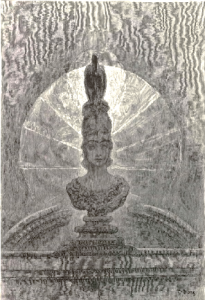

However, the stylistic and technical similarities, coincidental or not, do not compensate for the major difference with Poe; Poe’s metaphorical use of the raven is classic. With Poe, the raven visits a narrator who is mourning the death of his beloved, suggesting wisdom by sitting on the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber, driving the narrator to despair and insanity with his repeated nevermore.

The symbolism of the raven in Dylan’s song is completely unclear, and the description and meaning of the bird clash with the gist of the previous lines. “My love” is suddenly compared to a hellbird sitting outside the window, in the cold and rainy night, with a broken wing too. The same my love who just a moment ago spoke softly, winked and laughed floridly… no, the analysts will just have to accept that the poet is probably incorporating an irreducible insider wink here, less reducible than Middlemarch and gephyrophobia, anyway. Or that, even more likely, Dylan turns out to be a kindred spirit of Edgar Allan Poe in a third respect as well:

“The bust of Pallas being chosen, first, as most in keeping with the scholarship of the lover, and, secondly, for the sonorousness of the word, Pallas, itself.”

(Poe, The Philosophy of Composition, 1846)

“The sonorousness of the word”… exactly the same motivation that Dylan brings forward in 1978, when Ron Rosenbaum has him elaborate on the importance of the right sound: “It’s the sound and the words. Words don’t interfere with it. They – they – punctuate it.”

Years later, Dylan himself (or his entourage) stokes up the fire again, teasingly winking at the code crackers’ “Poe conclusion”. In 2012, fans can pre-order tickets for the Summer Tour via bobdylan.com. To do so, you need to enter a password. Someone in the Dylan firm has chosen as passwords: dirges, Gilead quaint, lattice, Leonore, methought, morrow, nepenthe, obeisance, Pallas, radiant and seraphim… yes, every word is taken from The Raven.

“The pallid busted phallus just above my chamber door,” as Oxford don William Archibald Spooner probably would say to that.

———-

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

The opinion expressed in the above article that the Poe reference is ‘rather thin’ is just wrong.

Artists on this side of the pond and the French Symbolises overseas were greatly influenced by the Gothic tales of Poe as well as by the musical sound of his poems:

So it be today. Dylan’s “Blowing like she’s at my chamber door” echoes Poe’s “As of someone gently rapping, rapping at much chamber door”, is just one example.

Dylan’s songs are infuenced by European artists, yes, but he is American to the core.

*at my chamber door” ,..,stupid computer!

See NSF Music Magazine ‘The Influence Of Edgar Allan Poe On Bob Dylan” –

which graciously gives me credit as the author though the article goes on further in exploring the Gothic writer’s influence than I believe I have in my Untold articles.

“It’s the sound and the words” be taken as the mantra of the “Rhyme And Rhythm School of Dylanology” but its members tend to ignore the ‘and the words’ part, and often suggest that any meaning there may be in the lyrics is of little importance.

The raven with the broken wing need not be taken as sinister at all….perhaps the raven is a symbol for a female lover who’s hurt because she’s been rejected by the male who got her pregnant (thus the reference to the country doctor).

The suggestion made elsewhere that a woman who comes to her lover in the morning must have been whoring about in the evening is likewise a sinister

imposition.

And speaking of sound..,, the way the words are emoted and the mood of the accompanying music give no indication that the rather sorrowful song is about a sinister creature, but instead is a deliberate reversal of Poe’s often dark gothic outlook.

I take great umbrage that Dylan’s words are essentially irrevalant as to having any meaning , and I respond thereto in a manner that I consider is well deserved.

The German poet be rather dark like Poe:

The raven was screeching, the leaves fast fell

The sun gazed cheerlessly down on the sight

We cold said to each other “Farewell”

(Heinrich Heine: Lyrical Interlude ~ translated))

More in tune with the Old Testament’s mention of Lilith, the screech owl, in her gothic abode:

The owl and also the raven shall dwell in it ….

The screech owl also shall be there

And find for herself a place of rest

There shall the great owl make her nest

And lay, and hatch, and gather under her shadow

(Isaiah 34: 11, 14, 15)

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/385/Love-Minus-ZeroNo-Limit

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.