The Mississippi-series, part 14

by Jochen Markhorst

Like earlier “Desolation Row” and “Where Are You Tonight?”, “Mississippi” can’t really be dealt with in one article. Too grand, too majestic, too monumental. And, of course, such an extraordinary masterpiece deserves more than one paltry article. As the master says (not about “Mississippi”, but about bluegrass, in the New York Times interview of June 2020): Its’s mysterious and deep rooted and you almost have to be born playing it. […] It’s harmonic and meditative, but it’s out for blood.

XIV Unca Donald

My clothes are wet, tight on my skin

Not as tight as the corner that I painted myself in

I know that fortune is waitin’ to be kind

So give me your hand and say you’ll be mine

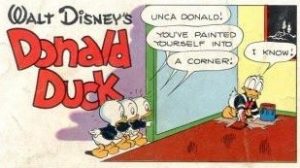

Claustrophobic words indeed, the words with which the narrator describes his current state of mind. Of course, the most famous scene of a hero trapping himself in the corner while painting is Donald Duck, but there it is not oppressive. Donald locks himself in to avoid an obligatory “social” with Daisy, so as not to have to accompany her to one of those stupid social events where Daisy is always so eager to show up.

Claustrophobic words indeed, the words with which the narrator describes his current state of mind. Of course, the most famous scene of a hero trapping himself in the corner while painting is Donald Duck, but there it is not oppressive. Donald locks himself in to avoid an obligatory “social” with Daisy, so as not to have to accompany her to one of those stupid social events where Daisy is always so eager to show up.

At first it is tempting to take the opening metaphor literally; wet clothes sticking to his skin… maybe he really did swim across that wide river to reach his beloved. But no – the second line, with the paint metaphor, suggests that the image of the wet, sticky clothes is a first step to yet another accumulatio, in this song the third accumulation of more or less similar images.

In terms of content we are back to the first accumulatio, in which the narrator also indicated to be “boxed in”, “trapped”, with “nowhere to escape”. This quatrain provides the corresponding images: the anguish of the tight, sticky clothes, and like Donald, painted into the corner, nowhere to escape.

The coincidental resemblance with Duckburg’s most famous resident will receive a remarkable psychological deepening in the next line. Fortune waiting to be kind are striking words to characterise the Donald Duck as it was created by Carl Barks. The brilliant Carl Barks, who managed to transcend the anonymity of “the good Duck artist”, is the creator of Duckburg, the creator of Scrooge McDuck and Gladstone Gander, of Neighbor J. Jones and the Beagle Boys, in short: of the Donald Duck as etched in our collective memory. He is the man who turns the side-figure Donald, the impetuous, frantic pusher next to Mickey Mouse (in The Wise Little Hen and in Orphan’s Benefit, 1934) into a protagonist with the image as we know him today: the Eternal Loser, the schmuck. Similar to Charlie Brown, for example, or Basil Fawlty – and to the narrator of “Mississippi”.

They are usually popular heroes with the public. Perhaps even more popular than the underdog, who usually wins at the end of the film or story. Dramatists can explain that phenomenon: a bad ending “you take home with you”, lets you lie awake at night. Shakespeare, Lessing, Brecht… that’s why they like to write tragedies, plays in which the main character has to die – because the impact is many times greater than a happy ending. The original storytellers were aware of that too, by the way. At Perrault, Little Red Riding Hood is eaten, and finito. No fuss with some hunter cutting open the wolf’s belly, and whatnot (Le petit chaperon rouge, 1697).

The less poignant variant of those fatal tragedies are the stories with the schmuck, who at least does survive his adventure. In Jewish humour and literature, the schmuck has existed as an archetype for centuries; in Western culture it has become increasingly popular since the second half of the twentieth century. Culminating in the 1990s, when Beck scores a mega hit with the schmuck’s signature song “Loser”, when The Big Lebowski becomes the new cult hero, when entire halls roar along with Radiohead’s “Creep” and comedians like Louis C.K. and Seth Rogen lay the foundation for their success: the loser personage.

The most heart-breaking then are the losers like Donald Duck and Charlie Brown, the unlucky ones who so often have happiness at their fingertips. In the music it is most movingly portrayed by John Hiatt in the beautiful song “You May Already Be A Winner” (Riding With The King, 1983):

Dry your eyes pretty girl I just got news from the outside world I don't know how they got our names But yesterday this letter came “Mr. and Mrs. Resident Dweller, your lucky number is… You may already be a winner!” Well, I've suspected this for years Still in all its good to hear They're pulling for us in the post To you my dear, I raise this toast

But the most beautiful words for exactly this state of mind are of course chosen by the Nobel laureate: “I know that fortune is waiting to be kind”.

Variants of the one-liner can be found in Dylan’s record cabinet. With Charlie Daniels for instance, on his rather obscure, nameless debut album from 1970, which he is allowed to record after he assisted Dylan on Nashville Skyline and on Self Portrait. It is a remarkably rugged, kaleidoscopic country rock album by an untamed, extremely talented ruffian (highlight is the closing “Thirty Nine Miles From Mobile”, a hard rocking, Allman Brothers-like jam), with halfway through the beautiful “Georgia”, which sounds like a left-over from Music From The Big Pink. In which Charlie sings:

All of my life I've been told That the LA streets was paved with gold Fame and fortune waiting to reward ya But it didn't take long to understand California ain't the promised land But at least a man's a man in Georgia

A more improbable, but bizarrely more striking source is an English Puritan Baptist preacher from the nineteenth century, the “prince of preachers” Charles Haddon Spurgeon, a prolific author of Christian books, hymns and sermons that are still popular in Calvinist circles today. In 1866 he collects all the psalms and hundreds of Christian hymns in Our Own Hymn Book, and number 499 therein, attributed to one Hewett, is called “Seek And Ye Shall Find”:

Come, poor sinner, come and see, All thy strength is found in me; I am waiting to be kind, To relieve thy troubled mind.

Still, Dylan does use the most unlikely sources. More attractive, however, is a source like Charlie Daniels. Or the so admired Bing Crosby (“quite a man, quite a singer,” as Dylan says in Theme Time Radio Hour), whose charming “Meet The Sun Half-Way” also has such a similar “fortune waiting to be kind”-oneliner:

Stop hiding behind a pillow whenever the dawn looks gray, Get up, get out, and meet the sun half-way! There may be a fortune waiting, or maybe an egg souffle, Get out, get out, and meet the sun half-way!

And this Bing Crosby song becomes even more attractive when the last verse is sung:

You may be a new Dick Tracy, conducting an exposé Get up, get out, and meet the sun half-way! Now don’t you blame your luck, say, do you want to sound like Donald Duck? You know, when you smile, you throw yourself a big bouquet!

But then again, Donald Duck would, obviously, have swam to the other side of that wide river without any problems.

And finally, the sweet closing line So give me your hand and say you’ll be mine completes the eclectic character of this exceptional quatrain.

Jesus has a small supporting role in Monty Python’s Life Of Brian (1979). We see him in the scene “Jesus’ Lack of Crowd Control”, the scene in which Brian and his mother, on their way to the stoning, do happen to pass by Jesus, just starting his “Sermon on the Mount”.

It is hardly a spectacular performance. Jesus speaks insecurely and too soft, the audience is noisy and easily distracted. “Mr. Cheeky” (Eric Idle) can’t stay focused either, and finds it more entertaining to harass the nose picking “Mr. Big Nose”.

MAN #2: You hear that? Blessed are the Greek.

GREGORY: The Greek?

MAN #2: Mmm. Well, apparently, he’s going to inherit the earth.

GREGORY: Did anyone catch his name?

MRS. BIG NOSE: You’re not going to thump anybody.

MR. BIG NOSE: I’ll thump him if he calls me ‘Big Nose’ again.

MR. CHEEKY: Oh, shut up, Big Nose.

MR. BIG NOSE: Ah! All right. I warned you. I really will slug you so hard–

MRS. BIG NOSE: Oh, it’s the meek! Blessed are the meek! Oh, that’s nice, isn’t it? I’m glad they’re getting something, ’cause they have a hell of a time.

The poor, pathetically awkward Jesus is played by Kenneth Coley, who can be admired in these same months in the BBC production Measure For Measure, the television adaptation of Shakespeare’s play. Coley will have seen the link with the “Sermon on the Mount” when rehearsing his text for Life Of Brian: For with what judgement ye judge, ye shall be judged: and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again (Matt. 7:2).

Kenneth Coley is standing at the same crossroads of Shakespeare and the Bible that will inspire Dylan more than once. “The Sermon on the Mount” provides references and idiom for songs like “Up To Me”, “Buckets Of Rain”, “Angelina”, “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “The Groom’s Still Waiting At The Altar”, and delivers in these same days of Life Of Brian and BBC’s Measure For Measure jargon and theme for “Do Right To Me Baby” (don’t wanna judge nobody, don’t wanna be judged).

Dylan used Measure For Measure’s plot a long time ago for “Seven Curses” (1963), although the format for this particular song probably is the old folksong “Anathea”. Presumably, 21-year-old Dylan is not yet that familiar with Shakespeare’s use of the same storyline – the plot around the dirty old judge who falsely promises a fair maiden to save her lover from the gallows in exchange for sex.

The young bard soon fills the knowledge gap. Shakespeare and his oeuvre still get only superficial name checks in “Highway 61 Revisited”, “Desolation Row” and “Stuck Inside Of Mobile”, but from The Basement Tapes Dylan processes longer quotes and paraphrases with more substantive relevance for the lyrics in question. “Tears Of Rage”, of course, and “Too Much Of Nothing” in particular, and Professor Christopher Ricks ultimately finds a total of forty references in Dylan’s oeuvre – although it should be noted: sometimes very far-fetched.

Not too far-fetched is this one appropriation in “Mississippi”, literally lifted from Measure For Measure:

DUKE VINCENTIO If he be like your brother, for his sake Is he pardon’d; and, for your lovely sake, Give me your hand and say you will be mine.

From the last act, in the BBC adaptation faithfully, spoken verbatim by Kenneth Coley, who in 1979 is the physical manifestation of the Dylan Crossroads, somewhere in Mississippi; the crossing of Shakespeare Alley and Sermon Mountain Row.

To be continued. Next up: Mississippi part XV: Gaze into the abyss

The Mississippi series

- The Mississippi-series, part 1; no polyrhythm here please

- The Mississippi-series, part 2: the line that never was.

- The Mississippi- series, part 3: Belshazzar on the steppe

- The Mississippi-series, part 4: Bertolt, Bobby, Blind & Boy

- The Mississippi-series, part 5: Frost in the room, fire in the sky

- The Mississippi-series, part 6: Charades

- The Mississippi series: part 7 : Dorsey Dixon

- The Mississippi-series, part 8: Pretty Maids All In A Row

- The Mississippi-series, part 9: Abandon all hope

- The Mississippi-series, part 10: Eyesight To The Blind

- The Mississippi-series part 11: Bonnie Blue

- The Mississippi-series, part 12: Roses Of Yesterday

- The Mississippi-series, part 13: Down in the Groove

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

But the ground is hard, and the night is black

Over here from the railway track

(Charlie Daniels: Georgia)

The ground is hard at times like these

Stars are cold, and the night is young

(Bob Dylan: Tell Old Bill)

*railroad track