by Jochen Markhorst

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 1: London Bridge Is Falling Down

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 2: A service with a real preacher

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 3: You got a fast car

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 4: What’s so bad about misunderstanding?

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 5: Maybe we should put that there

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 6: The Levee’s Gonna Break

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 7: Greetings from Vicksburg

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 8: The Portable Henry Rollins

- High Water part 9: I just thought that was the way he spelled his name

by Jochen Markhorst

X The Return of Jerry Lee

Well, George Lewis told the Englishman, the Italian and the Jew “Don’t open up your mind, boys, To every conceivable point of view.” They got Charles Darwin trapped out there on Highway Five Judge says to the High Sheriff “I want him dead or alive Either one, I don’t care.” High water everywhere

The day the music died was, of course, 3 February 1959, the day Buddy Holly crashed near Clear Lake, Iowa. But entirely alive and kicking she had not been for awhile anyway, that fateful day. The first blow was dealt 257 days before, Black Monday 24 March 1958, the day Elvis reports to the barracks at Fort Chaffee to do his military service; the next blow is just 59 days after that, and hits much harder: 22 May 1958, Jerry Lee Lewis arrives at Heathrow Airport for a UK tour. Among the welcoming committee is Paul Tanfield, a reporter from the Daily Mail, and Paul has his eyes open. “And who are you,” he asks the young girl who catches his eye in Jerry Lee’s entourage. “I’m Myra, Jerry’s wife,” replies Myra Gale Lewis naively, proudly and truthfully. Tanfield turns to The Killer and asks the question that will torpedo Jerry Lee’s career: “And how old is Myra?” “Fifteen,” Lewis lies. Myra is thirteen, and he also wisely conceals the fact that Myra is not only his wife, but also his niece. And that he is now a bigamist (they got married five months before Jerry Lee’s divorce from his second wife).

The day the music died was, of course, 3 February 1959, the day Buddy Holly crashed near Clear Lake, Iowa. But entirely alive and kicking she had not been for awhile anyway, that fateful day. The first blow was dealt 257 days before, Black Monday 24 March 1958, the day Elvis reports to the barracks at Fort Chaffee to do his military service; the next blow is just 59 days after that, and hits much harder: 22 May 1958, Jerry Lee Lewis arrives at Heathrow Airport for a UK tour. Among the welcoming committee is Paul Tanfield, a reporter from the Daily Mail, and Paul has his eyes open. “And who are you,” he asks the young girl who catches his eye in Jerry Lee’s entourage. “I’m Myra, Jerry’s wife,” replies Myra Gale Lewis naively, proudly and truthfully. Tanfield turns to The Killer and asks the question that will torpedo Jerry Lee’s career: “And how old is Myra?” “Fifteen,” Lewis lies. Myra is thirteen, and he also wisely conceals the fact that Myra is not only his wife, but also his niece. And that he is now a bigamist (they got married five months before Jerry Lee’s divorce from his second wife).

The press jumps on it, and after three dramatic shows, both Jerry Lee Lewis and the rest of the tour are cancelled.

Back home in Memphis, Sun Records’ Sam Phillips may understand that they need to do something about damage control, but the legendary studio boss proves to be bizarrely bad at assessing the seriousness of the situation. Even lying would probably have been a better option than the terribly stupid strategy they decide on: downplaying.

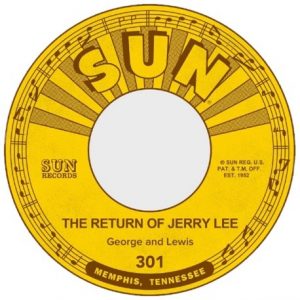

He acts fast, though. Phillips puts his right-hand man, Jerry Lee’s discoverer Jack Clement to work. Within a week, 30 May “The Return Of Jerry Lee” is recorded in his studio and 15 June the single is already on the shelves. Sam makes a few phone calls and on 23 June 1958, i.e. a month after the Heathrow debacle, we read on page 4 of the entertainment industry’s leading newsweekly, The Billboard, an announcement of a “disc for jocks this week”, plus an explanation from the Sun Records boss himself under the heading ‘Return’ Disk Laughs It Off:

“This one has an announcer at Memphis Airport, greeting the chanter on his return from London, with an interview. Lewis’ answers are dubs taken from his past disks. Phillips said: “We think it’s a cute record. It makes light of the whole British episode, which is the way we think the whole thing should be treated anyway.” Phillips added that the disk, now being sampled by various jocks, has met a good early response. At present it’s a one-sider, but if the reception holds up Phillips said, he will issue it commercially with a flip called Jerry Lee’s Boogie.”

Sam Phillips tries to package a scandal uniting paedosexual, incestuous and bigamist unsavouriness as “the British episode”, which, moreover, we should not take too seriously: it should be treated lightly anyway. It fails – obviously – spectacularly. As does the “cute record”, a tantalisingly unfunny pastiche of “interview questions” and snatches of Lewis songs as answers. For example:

Mr. Lewis, I’d like to ask you this question: how do you feel about being back home?

Ooh, feels good! [uit “Great Balls Of Fire”]

Well, Jerry, what did you say when the news of your marriage broke over in London?

Our news is out

All over town [uit “You Win Again”]

Well, how did you manage to get your marriage license with your wife being so young?

I told a little lie [uit “I’m Feeling Sorry”]

Jerry Lee Lewis – The Return of Jerry Lee:

More surprising than the predictable flopping is the artist name under which the single is released: George and Lewis. Chosen because the “interviewer” is voiced by George Patrick Klein. And that, this artist name George and Lewis, seems already a more likely trigger for the name choice “George Lewis” in the opening of “High Water’s” fifth verse than some George Lewes from the nineteenth century or a clarinet-playing George Lewis from New Orleans. At least of Jerry Lee Lewis we know for sure that he is deep under Dylan’s skin – deep enough to be allowed to bounce around in Dylan’s stream of consciousness, anyway.

As early as 1969, Dylan confesses to Jann Wenner that he wrote “To Be Alone With You” for Jerry Lee Lewis; he often mentions him as an admired artist, and in 2006, in the USA Today interview with Edna Gundersen, he even mentions Jerry Lee Lewis as one of the “performers who changed my life”. On this same album “Love And Theft”, we’ve heard Jerry Lee before, by the way; the intro for No 2, “Mississippi”, Dylan copied from The Killer’s awkward ode to JFK, from “Lincoln Limousine” (1966).

Jerry Lee Lewis – Lincoln Limousine:

And a few years hereafter, DJ Dylan, as a radio producer on Theme Time Radio Hour, expresses his love for “the piano pounding madman” often and gladly. No fewer than seven times the DJ finds an occasion to play a Lewis song (putting The Killer in the Top 3 most-played-artists), each time introduced and celebrated with words that show not only love and respect, but also knowledge of the man’s biography. “Let’s talk about the man who argued with Sam Phillips about his eternal soul. Of course I’m talking about the Ferriday Flash, Jerry Lee Lewis,” for example, and the very first time the DJ puts a Jerry Lee single on his turntable, 20 September 2006, Episode 21, School:

“That was Jerry Lee Lewis, “High School Confidential”. If you see it in the movie theatre, with Jerry singing the title song, take a look at the bass player. That’s J.W. Brown. His daughter, Myra Gale, married Jerry Lee. That didn’t go over too good, ’cause she was quite young. Jerry was on tour overseas when news of his marriage came out in the press. “High School Confidential” dropped right out of the charts and Jerry’s career was never the same. I wonder if Myra dropped out of school.”

Content-wise, no links to this fifth verse of “High Water”, of course. At most, the combination of Jerry Lee’s problems with justice and his getting cancelled on the one hand, and “High Sheriff”, the hunt for Charles Darwin and “wanted dead or alive” on the other, may have led to the click in Dylan’s creative flow that then causes “George Lewis” to bubble up – but in the end, that’s as thin as trying to want to hear “George Lewes” and then making the click with Darwin.

No, in the end we will find the strongest candidate closest to home, on the waterfront, in the bulging song treasure of Dylan’s inner jukebox, where we will see an unsteady hanging bridge from one “George Lewis” to “High Water”.

Then again: “None of this has to connect,” as Dylan says to a timid Sam Shepard at their first encounter in 1975. “In fact, it’s better if it doesn’t connect.”

To be continued. Next up High Water (For Charley Patton) part 11: “De ballit I like bes’, though, is de one ’bout po’ Laz-us”

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B

May I just add a comment: on the day Jerry Lee Lewis died I was in Nottingham, England, to see Dylan perform, and very unusually for the tour he came back on stage for an encore, announced that Jerry Lee had passed away, and played a tribute to him. You can see a video of the occasion at

https://bob-dylan.org.uk/archives/24295

From movie Dead Man

John Dickinson (Robert Mitchum) ~

I want him brought back here to me –

dead or alive doesn’t matter

though I reckon dead would be easier

correcrtion:

don’t matter