- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 1: London Bridge Is Falling Down

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 2: A service with a real preacher

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 3: You got a fast car

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 4: What’s so bad about misunderstanding?

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 5: Maybe we should put that there

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 6: The Levee’s Gonna Break

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 7: Greetings from Vicksburg

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 8: The Portable Henry Rollins

- High Water (for Charley Patton)part 9: I just thought that was the way he spelled his name

- High Water (for Charley Patton) part 10:The return of Jerry Lee

- High Water (for Charley Patton)part 11: “De ballit I like bes’, though, is de one ’bout po’ Laz-us”

- High Water (for Charley Patton)part 12: You can never tell why someone’s gonna stick something in a song

- High Water (for Charley Patton) (2001) part 13: The sum of its parts

- High Water part 14: Just grab something off the shelf

High Water (for Charley Patton) (2001) part 15

by Jochen Markhorst

XV “A roulette wheel rolling round in his head”

I’m gettin’ up in the morning—I believe I’ll dust my broom Keeping away from the women I’m givin’ ’em lots of room Thunder rolling over Clarksdale, everything is looking blue I just can’t be happy, love Unless you’re happy too It’s bad out there High water everywhere

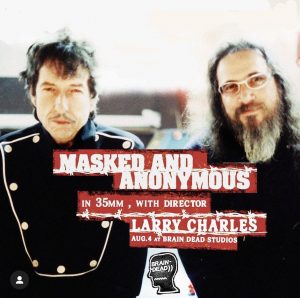

“He has these fragments, these bits rolling round in his head all the time and he’s constantly – almost like a roulette wheel – trying different bits together and seeing what happens.” Trev Gibb interviews director and screenwriter Larry Charles by phone in 2003 for the Masked And Anonymous Database (published in Isis #113, 2004). For a time, Charles is in the unique and enviable position of seeing Dylan creating right before his eyes, sitting with him at a worktable, being able to see and hear the cogs turning in Dylan’s head up close – during the period when Dylan is recording both “Love And Theft” and the film Masked And Anonymous. So Charles does have some authority and right to speak, he is sharp and eloquent, and fortunately, he is quite open about his Dylan observations in interviews.

“He has these fragments, these bits rolling round in his head all the time and he’s constantly – almost like a roulette wheel – trying different bits together and seeing what happens.” Trev Gibb interviews director and screenwriter Larry Charles by phone in 2003 for the Masked And Anonymous Database (published in Isis #113, 2004). For a time, Charles is in the unique and enviable position of seeing Dylan creating right before his eyes, sitting with him at a worktable, being able to see and hear the cogs turning in Dylan’s head up close – during the period when Dylan is recording both “Love And Theft” and the film Masked And Anonymous. So Charles does have some authority and right to speak, he is sharp and eloquent, and fortunately, he is quite open about his Dylan observations in interviews.

Larry considers the trio Time Out Of Mind, “Love And Theft” and Masked And Anonymous as one Dylan period, similar to the born-again period and the electric period, and he does have a point. A point he can substantiate:

“He was working on “Love And Theft” at the same time and in fact I had the privilege of going into the recording studio and what happens is, a lot of lines that didn’t wind up in ‘Masked and Anonymous’, wound up in “Love And Theft” and vice versa. Again we’re mixing and matching and sort of making our own puzzle.”

… the similar method of work, then, the back-and-forth of usable lines, the “mixing and matching” of which we hear Larry give an example ten years later in that You Made It Weird podcast, 2014 (the I’m no pig without a wig line from the third stanza). But beyond that working method, Charles also sees a distinctive stylistic feature of this, let’s call it “puzzle period”: a kind of retro-quality, old-fashioned warmth, comparable to what in fantasy culture is called steampunk. “Quaintness”, as Larry Charles puts it;

“If you listen to “Love And Theft” it’s there too. And I think this is part of that same period in his work, which is the juxtaposition of the old and the quaint, and the old-fashioned with the post-modern. He’s trying to really juxtapose those forms and see what happens.”

An art historian with a red pencil would probably put one or two crosses, but we get what Charles means; postmodernism without the irony and without the anarchy, something like that. After all, Dylan has been mixing and matching since the 1960s, but indeed, in those years, in songs like “Highway 61 Revisited” and “Gates Of Eden”, qualities like irony, anarchy and surrealism overshadow the warmth, the “quaintness”. From the late 20th century, Dylan tends towards the style that Larry Charles tries to capture in words, a style that can be illustrated with an image like early Roman Kings in their sharkskin suits, bowties and buttons, high top boots, with a mise-en-scene like Charles Darwin trapped out there on Highway Five. Which, incidentally, is just as true of the sound, although Charles doesn’t seem to mean that. Dylan has turned away from searching for the more chilly mercurial sound, finding his Holy Grail now in the sound of these old blues recordings, Little Walter, guys like that, as engineer Mark Howard explained to Uncut in 2008.

The fragment, the bits rolling around in his head as Dylan conceives this final couplet is, of course, effortlessly identified by every music fan:

I’m gettin’ up in the morning, I believe I’ll dust my broom

Girlfriend, the black man that you been lovin’, girlfriend, can get my room

… Robert Johnson’s immortal, indestructible “I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom” from 1936. And otherwise the standard Elmore James made of it, preferably the 1951 recording, which opens with practically the same words:

I’m gettin’ up soon in the mornin’, I believe I’ll dust my broom

I quit the best gal I’m lovin’, now my friends can get my room

Robert Johnson, by the way, is not actually the real father – he in turn borrowed the phrase from Kokomo Arnold’s 1934 “Sagefield Woman Blues”, and Kokomo had probably heard it from the Sparks Brothers, in 1932’s “I Believe I’ll Make a Change” or Jack Kelly’s 1933 “Believe I’ll Go Back Home”, all of which, apart from the shared use of dust my broom, also have a similar melody to Johnson’s monument.

But Johnson singles out the phrase and elevates it to a title, and – obviously – has his own magic to turn it into the better song. And, on a side note, in the centre of the manuscript we decipher, scribbled in blue in between, something with raining down in Arkansas – which seems to echo Johnson’s “Terraplane Blues” (I got a woman that I’m lovin / way down in Arkansas), suggesting that at this stage of the creation Robert Johnson indeed is haunting Dylan’s mind.

Dylan himself performed “Dust My Broom” one single time, and seems to use the standard set by Elmore James as a template. Which is also the version DJ Dylan plays on his radio show (episode 50, Spring Cleaning, April 2007), introduced with the appreciative words “Speaking of brooms… here we have Elmore James with a song that’ll drive you ’round the bend.”

Elmore’s golden find, of course, is the opening lick, which has become the Mother Of All Blues Licks. The lick also dominates Dylan’s one-off performance 12 November 1991 in Detroit. For this one song a local axe grinder, the rather unknown guitar player Tino Gross is invited on stage, and he indeed duly discharges his duty to play the role of Elmore James. A tip from Detroit’s hero The Nuge Motor City Madman Uncle Ted Nugent apparently; “Thank you Ted Nugent,” Dylan says without further comment after the final chord.

It made a lasting impression on Tino Gross. A blues blogger asks him almost a quarter-century later if he could name a “life-changing” experience. Tino, who after all has also played with men like Bo Diddley, RL Burnside and John Lee Hooker, doesn’t have to think twice:

“For me personally, it was being invited to play guitar with Bob Dylan at a sold out show in Detroit at the Fox Theatre. I’ll never forget that night as long as I live. I am a huge Dylan fan, so to be able to play with him was amazing! It doesn’t happen everyday.”

(Michael Limnios Blues Network, Blues.Gr, 14 December 2014).

After this copied classic as an opening line the “roulette wheel” in Dylan’s head, as Larry Charles calls it, stops in a surprisingly predictable place: the word “broom” triggers the nineteenth-century country song “The Bald-Headed End Of The Broom”, from which Dylan copies as verbatim as from Robert Johnson’s song:

Boys I say from the girls keep away Give them lots of room When you’re wed they will hit you on the head With the bald-headed end of the broom

Registered in the Roud Folk Song Index as “Baldheaded End of the Broom” and attributed to an American songwriter, one Harry Bennett, who released it in 1877 as “Boys Keep Away from the Gals”. But an educated guess is that Dylan heard his old mate Martin Carthy’s version shortly before “High Water”. Carthy, from whom Dylan learned “Scarborough Fair” in a grey past in London, and to whom we thus owe “Girl From The North Country”, released the album Broken Ground with The Watersons in 1999, featuring the infectious “The Royal Forester / The Bald Headed End of the Broom”. It is a highlight of the album, and so is rightly selected two years later for the collector The Carthy Chronicles, which hits shops on 10 April 2001 – five weeks before Dylan records “High Water”.

“He has these fragments rolling round in his head all the time and he’s constantly trying different bits together and seeing what happens.”

To be continued. Next up High Water (For Charley Patton) part 16: Greetings from Clarksdale

—-

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B

Incorporating the “”I don’t know what it means” doctrine into Structuralist-leaning”Dylanology” is one thing, but interpreting the doctrine as asserting that Dylan lyrics are quite often nonsensical is another.

~Sound need not compromise meaning even though the piece be fragmented and ambiguous.

Rather a listener (or an analyst) can participate in the creative process by seeking out a plausible unity.

Indeed, words are chosen as if by a the roller from a roulette wheel – but only when the bet gives better returns as to some possible reasonable meaning( narrative/feeling / sense) to the musical poem as a whole .

Man disappears into rabbit hole, emerges days later talking about brooms.

♂️

The emoji of a detective did not load, unfortunately

Not to worry:

‘Twas Poe’s detective who solved how come a mirror- image of the label from Handel’s “Messiah” is pressed under the label of some Dylan bootlegs called “Zimmerman Looking Back”, and why the theme of steadfastness contained in both recordings are similar.

Both refer to biblical lines like:

For thou hast been a strength to the poor

A strength to the needy in his distress

A refuge from the storm

(Isaiah 25: 4)

And:

The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light

They that dwell in the land of the shadow of death

Upon them hath the light shined

(Isaiah 9:2)

As in:

Why only yesterday I saw somebody on the street

That was really shook

But this old river keeps on rolling though

(Bob Dylan: Watching The River Flow ~ from “Looking Back”)

According to detective Dupin, an invisible parallel galaxy sliced into the Milky Way just at the right time to entangle messages contained in the Dylan and Handel recordings.