- Jet Pilot (1965) part I: Greetings from Vermillion

- Jet Pilot (1965) part II: I threw it all away

- Jet Pilot part III: A whole lotta woman

- Jet Pilot part IV: What is the most important thing in your life?

by Jochen Markhorst

V The mixed up, muddled up, shook up world

She got all the downtown boys, all at her command But you've got to watch her closely 'cause she ain't no woman She's a man

“Down Town” is still in the air, when Dylan shakes his verse with the downtown boys out of his sleeve. In the third week of 1965, Petula Clark is number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, the first in a long line of American hits for Petula. On the day Dylan records “Jet Pilot”, 5 October, “Round Every Corner” has just entered at no. 85, after she has scored a Top 3 hit with “I Know A Place” (and the next no. 1 hit, “My Love”, follows). A good year, then, for Petula, but Dylan cannot complain either; in this same week chart (3-9 October 1965), three Dylan songs are making money: “Like A Rolling Stone” on 33, “Positively 4th Street” on 34 and The Turtles’ Top 10 hit “It Ain’t Me Babe” is also still there, on 29.

“Down Town” is still in the air, when Dylan shakes his verse with the downtown boys out of his sleeve. In the third week of 1965, Petula Clark is number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, the first in a long line of American hits for Petula. On the day Dylan records “Jet Pilot”, 5 October, “Round Every Corner” has just entered at no. 85, after she has scored a Top 3 hit with “I Know A Place” (and the next no. 1 hit, “My Love”, follows). A good year, then, for Petula, but Dylan cannot complain either; in this same week chart (3-9 October 1965), three Dylan songs are making money: “Like A Rolling Stone” on 33, “Positively 4th Street” on 34 and The Turtles’ Top 10 hit “It Ain’t Me Babe” is also still there, on 29.

But downtown boys is of course not the punchline, or the earcatcher of the rejected miniature “Jet Pilot”.

Transgender protagonists, and themes such as transsexuality and gender confusion, have been bon ton in pop music since the 1990s. Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way”, Blur’s “Boys And Girls”, “A Girl Called Johnny”, Green Day’s “She”… with Christina Aguilera’s “Reflection”, the theme has even entered the mainstream and Disney films in a watered-down form.

The way was paved twenty years earlier by superstars like David Bowie and Lou Reed, who not only thematised gender confusion in world hits (“Walk On The Wild Side” and “Rebel Rebel”, for example), but also made it part of their image. T. Rex’s Marc Bolan is the pioneer in 1971, but the success of Reed and Bowie breaks the dam. Glam rock becomes a new sub-current – the long-haired, eye-shadowed, rouged, lip-sticked and androgynously dressed men of bands like The Sweet, Mott The Hoople and Queen.

As a punchline of a pop song, it is of course a bit older than Marc Bolan. “Lola” has the scoop on that. After all, it is only in the last verse that it becomes clear that Lola is a man;

She said, "Little boy, gonna make you a man" Well I'm not the world's most masculine man But I know what I am and I'm glad I'm a man And so is Lola Lo-Lo-Lo-Lo-Lola

In the same borderland, Pink Floyd had already done pioneering work three years earlier, when the genius crackpot Syd Barrett still has some sense and is able to write brilliant gems like “See Emily Play” and “Lucifer Sam”. The first single “Arnold Layne” (March ’67) sings about a cross-dresser, with, intentional or not, a small Dylan reference;

Arnold Layne had a strange hobby Collecting clothes moonshine washing line They suit him fine On the wall hung a tall mirror Distorted view, see through baby blue He dug it

Incidentally, based on facts, according to Roger Water: “Both my mother and Syd’s mother had students as lodgers because there was a girls’ college up the road so there were constantly great lines of bras and knickers on our washing lines and ‘Arnold’ or whoever he was, had bits off our washing lines.” The Arnold in the song does not end well. They gave him time, doors bang, chain gang he hates it.

But even the unbridled taboo-breaking free-thinker Syd Barrett is not the first to visit these caverns. In that October week in 1965, when Dylan runs his finger through the Billboard Hot 100 to see how his new and his old single are doing, he undoubtedly lingers at number 55.

Radio broadcaster Dylan announces the band with some sympathy, in November 2007 (Theme Time Radio Hour, episode 57 “Head To Toe”):

“There’s a lot of groups that people think are one-hit-wonders. One band that always ends up in that list, is the Barbarians. Their drummer was named Victor Moulton, but everyone knew him as “Moulty”. At age 14, a home-made pipe bomb exploded and he lost his hand. He got a metal hook, much like Captain Hook. He was still a great drummer, and I think, that hook brought a certain punk credibility to the band.”

That’s what Dylan tells us in introduction to a sort of autobiographical song by drummer Victor Moulton, to “Moulty”, a catchy “Hang On Sloopy” rip-off from 1966. But that’s not the hit he refers to when the DJ calls The Barbarians a one-hit-wonder – that would be the modest hit “Are You A Boy Or Are You A Girl”.

The song achieves a certain status because it is often selected for compilation albums, notably on the 1998 re-issue of the legendary Nuggets: Original Artyfacts from the First Psychedelic Era, 1965-1968. Actually, though, like the band itself and the rest of their output, it’s rather trite. Their only, quite forgettable, LP from 1966, is otherwise filled with two songs of their own and poor covers of modern classics like “Susie Q” and “Memphis, Tennessee”. Especially The Barbarians’ adaptations of “House Of The Rising Sun” and “Mr. Tambourine Man” are deplorable, despite their “punk credibility”.

Still, the pop premiere for a song thematising gender confusion is in their name, with that song reaching its top position in Billboard on the same day when Dylan half-improvises: you’ve got to watch her closely ’cause she ain’t no woman, she’s a man.

https://youtu.be/yDpGsFI3WNg

Dylan, however, does give it a “Lola” charge. The Barbarians articulate, ironically, conservative wailing from a disapproving old nag;

Are you a boy, or are you a girl? With your long blond hair you look like a girl Yeah, you look like a girl You may be a boy (Hey) you look like a girl

… and continue with a somewhat obvious, yet charming nod to The Beatles and to Dylan:

You're either a girl or you come from Liverpool (Yeah, Liverpool) You can dog like a female monkey, but you swim like a stone (Yeah, a rolling stone) You may be a boy (Hey) you look like a girl

The reassurance that it is ironic can be distilled from the appearance of the band; although no wildly waving blonde manes, no freak flags flying, they are indeed – by the standards of 1965 – long-haired themselves.

It’s a pity, though, that Dylan leaves it at this one unfinished sketch, rejecting “Jet Pilot” on the same day again, 5 October. After all, it could have been the blueprint for “Lola”, for “Walk On The Wild Side”, for “Rebel Rebel”, for all those little masterpieces that thematise female he’s and male she’s. Fortunately, they achieved immortality on their own, without “Jet Pilot”, making the world a little more beautiful in doing so. Although never on the astronomical level of the stoning scene in Monty Python’s Life Of Brian, obviously. Where men who play women have to dress up as men to avoid being seen as women. It’s a mixed up, muddled up, shook up world.

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

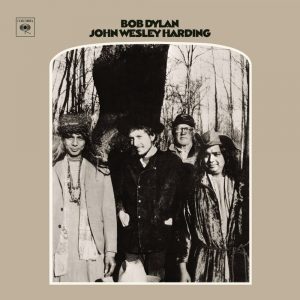

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits (German)

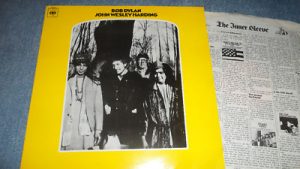

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

And elsewhere

There are details of some of our more recent articles listed on our home page. You’ll also find, at the top of the page, and index to some of our series established over the years.

If you have an article or an idea for an article which could be published on Untold Dylan, please do write to Tony@schools.co.uk with the details – or indeed the article itself.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with getting on for 10,000 members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

Stretching my criteria somewhat (because the song is short and surely everyone knows it off my heart so I thought I might squeeze in)

which is not the politest thing ever said. That is perhaps a line in a different category – great, challenging lines, which have become commonplace among the Dylan audience, but which really ought to be taken out of context and considered, just occasionally.

However as my meanderings continued I found that what I really wanted were lines that even some Dylan fans who know the works very well might take a moment to place, and which having placed the lines they would perhaps really think about for some time, out of the context of the song from which they came.

The point being that having the lines divorced from the rest of the song, the sheer enigma of some of Bob’s writings can be felt full-on. (Or at least that is how it seems to me).

To give an example

You might of course immediately say “Dirge” and you’d be right, but what exactly does it mean, and why, does that line does it stay with me? It is, I suppose, the juxtaposition of the martyr crying for the sins of humanity, while the angels – God’s celestial intermediaries – are to be found playing with sin. I don’t fully get it, but the image has been occupying my mind since I first had the idea for this little meander, last weekend.

Of course obscurity isn’t everything, nor is it, I find, essential. I mean I get the meaning of

which gives us a simple image of not owing anyone for the favours of the past, but it is said in a way that seems to give the lines a deeper meaning.

Some of the lines I thought of are descriptions of feelings but done in such an interesting way that although the words are simply everyday language a single line can give me a sense of “otherness”, of being somewhere else, unknown, unknowable. As in…

A nameless place is impossible, a contradiction, everywhere has a name. It is what humanity does – it gives names out to everything. And yet it is a feeling I have shared on some occasions; a feeling of being utterly lost in terms of my own place within the world. A nameless place is a place without meaning, so being stranded there is to have no meaning in one’s life…

Sometimes in doing this I come across lines which are known by every fan, I’m sure, because the song is so brilliant, but the meaning of which is still obscure, and yet one can absolutely feel it at certain times.

Of course in flipping around through the songs I have come across some whose meaning is not obscure, but where, in so few ordinary everyday words, Dylan manages to capture the depths of a specific emotion. For example,

is one of those. One meets a person and really feels drawn to that person, and yet they show no reciprocation, no interest. I can’t recall that emotion expressed so succinctly elsewhere. Maybe I should do a search for that category of “clear emotions expressed, but not as expressed by others, in obscure lines of Dylan” except that is getting a bit complicated.

But from the same song I immediately think of another such line

The line is clear in its meaning, but who will? I am not sure “Tell Ol’ Bill” really tells us.

If you have such lines – lines that just really seem to have no meaning at one level, but which in ways that can’t be expressed, do have an untouchable meaning at another level – do write in and tell me.

Do you have a tale to tell via Untold Dylan?

We now have over 2000 articles on this site, and many of them are personal tales about attending a concert, listening to Dylan, cover versions, or the individual writer’s own appreciation of Dylan and his music.

These articles are written for Untold by Dylan fans, and if you have a view of Dylan that you feel could be of interest to others, we’d love to hear from you.

To see the variety of approaches we have included in this site, just go to the top of the page and look at the various headings under the picture – each one contains an index of articles on a Dylan theme. Or look at the latest series listed on our home page. If you write a piece you can add to these, or create your own theme, or simply send in a one-off contribution. As long as it gives a different insight into Dylan and his work, we may be well interested in publishing it.

Sadly, we don’t have the funds to pay, but Untold Dylan does have a very wide readership, so your work will be seen by a huge number of people. If you have an article please email Tony@schools.co.uk If the article is ready, please attach as a word file.

One other thing: we never ask for donations, and we try to survive on the income from our advertisers, so if you enjoy Untold Dylan, and you’ve got an ad blocker, could I beg you to turn it off while here. I’m not asking you to click on ads for the sake of it, but at least allow us to add one more to the number of people who see the full page including the adverts. Thanks.

And one other, other thing: we also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8500 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down