A list of all the previous articles in this series is given at the end.

by Patrick Roefflaer

- Released January 19, 1976

- Photographers Ken Regan, Ruth Bernal, Stephanie Chernikowsky

- Collage Carl Barile

- Liner Notes Allen Ginsberg & Bob Dylan

- Art-director John Berg

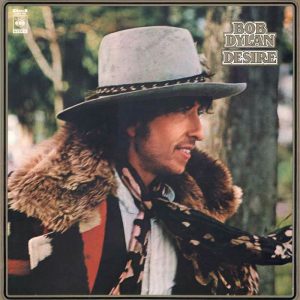

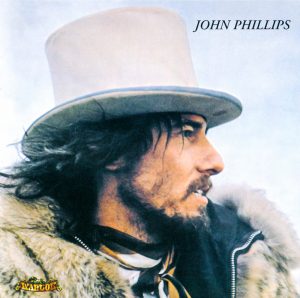

In books or websites about album covers, Desire’s front cover is often depicted next to that of John Philips’ self-titled solo debut (1). It is often presented as an example of plagiarism or parody.

In books or websites about album covers, Desire’s front cover is often depicted next to that of John Philips’ self-titled solo debut (1). It is often presented as an example of plagiarism or parody.

There are indeed quite a few similarities between the portraits of Dylan and those of the ex-leader of The Mamas and the Papas: on both covers we see the singer in profile, looking to the right. Both wear a grey felt hat, a scarf, and a coat with a collar of fur.

Too much to be accidental? John Berg, who was responsible for the design of the Desire cover, strongly denies that there is any influence: ‘No. I never even saw that [John Phillips cover]. I can’t imagine how I could plagiarize something I’ve never seen before.’ So Dylan is responsible. After all, he chose the photo.

The Rolling Thunder Revue

In June 1975, Dylan moved back to New York to prepare for a new tour.

As he didn’t like the large-scale approach of his previous tour with The Band in 1974 (see Before the Flood), he searched for a new approach. The idea is to set up an itinerant show, to travel around and appear in small concert halls or even in coffee houses, without much publicity.

The core of the Rolling Thunder Revue is a regular band, but when they visit a city, local artists are invited to join them for the show.

For the design, Dylan calls on Jacques Levy, a New York writer and dramaturge. Levy wrote and directed the scandalous musical Oh Calcutta! and collaborated with Roger McGuinn on two dozen songs for The Byrds, including ‘Chestnut Mare’.

Dylan was impressed enough to ask him to collaborate on some songs together. Of the nine songs on Desire, Levy is credited as co-author.

Levy designs a décor that gives the Revue the appearance of an old-fashioned variety show. It starts with a yellow stage curtain with the name of the tour in circus letters. When the curtain is raised, a group of gypsy-like musicians becomes visible, standing on a large carpet.

“I was able to make it all very theatrical,” Levy explained. “At the beginning of the evening I had the whole band come on and everyone did a song. In between the songs, I put everything in a shadowy blue. People came up and people went off.” The setlist is built up to a grand finale – the performance of Dylan himself – followed by the encores with the whole gang together on stage.

Such a spectacle lends itself perfectly to a film adaptation. Dylan hires two professional film crews who film all the performances. But also during rehearsals and informal sessions the cameras keep running.

It soon becomes clear that Bob has a film in mind that would involve much more than a simple concert recording. It has to be a Fellini-like work of art, with Bob, his wife, and his friends playing dramatic scenes. Sam Shepard is hired to write a script. The brief is simple but confusing: “There doesn’t have to be coherence in it. One-third of the film is improvised, one-third is fixed and one-third is pure luck.” The young stage director is not sure what to do, and looking back concludes: “In the end, we didn’t write a script at all.” Instead, Shepard keeps a diary (2).

Unsurprisingly, the resulting four-hour film, Renaldo And Clara, is quite chaotic.

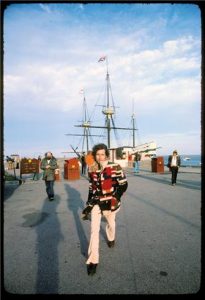

On Halloween, October 30, 1975, the Rolling Thunder Revue kicks off with a show in Plymouth, Massachusetts. According to Bob’s intention, the War Memorial Auditorium is a small hall that can hold only 1,800 spectators, in a city where rarely any renowned artists pass.

On Halloween, October 30, 1975, the Rolling Thunder Revue kicks off with a show in Plymouth, Massachusetts. According to Bob’s intention, the War Memorial Auditorium is a small hall that can hold only 1,800 spectators, in a city where rarely any renowned artists pass.

Of course, the choice of location was no coincidence: Plymouth famously is the place where, in 1620 the ship the Mayflower dropped anchor, where the first European pilgrims set foot on land. That was the first step towards the Declaration of Independence of the United States, on July 4, 1776 — an event whose 200th anniversary will be celebrated exuberantly when the film is released. (Although disappointingly, the premiere will only occur in January 1978).

The first day of shooting is October 31. Some improvised scenes are shot on the location. Dylan and his company (Roger McGuinn, Bobby Neuwirth, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, and a bearded man in a cowboy hat) pretend – somewhat predictably – that they come ashore with a boat.

Further scenes are shot when they visit the Mayflower II (a replica of the original boat), the famous Plymouth Rock, and Memorial State Park.

The photo that adorns the cover is made in that park, by Ken Regan.

Ken Regan

On the occasion of the release of his book All Access: The Rock ‘n’ Roll Photography of Ken Regan in 2011, the photographer revealed to Sean Fennessey how he became the only official photographer of the Rolling Thunder Revue (1975-76).

“That was because of (promoter) Bill Graham. I worked for some magazines and Time called me up: “We want to do something about Bob Dylan. He’s going on tour with his band and it’s the last tour with The Band.” I said, “I don’t know if that’s going to work. Bob is very concerned about his privacy […], but I’ll see what I can do.”

He calls Bill Graham. Graham shows Dylan some pictures of Ken and he gets his permission. “So Time sent me to Chicago. Bill was there and he introduced me to the big shots there. Finally, I got to join Bob. He was friendly and said he liked my pictures. ‘Don’t get in my way,’ he said. ‘Take pictures as much as you want of everyone who’s on stage, but backstage is taboo.’ Fine for me.

“That first night, I stood in the wings, doing my best to stay out of his sight. Fantastic experience. I’m always looking for a new angle and thought to take some pictures of the audience. In the second row I saw a lady in her sixties – grey hair and glasses on – and she was jumping and applauding. It was a beautiful sight, because she was surrounded by all young people.

“The next night I saw Bill, he told me that Bob hadn’t said anything and that it was okay. I asked him about that woman in the second row. He shouted, ‘Did you photograph her? That’s Bob’s mother. Don’t do anything with those photos because if Bob notices that, you’ll never come close to him again.’

“Time published some of my photos and I was over the moon. It was only the second time that a photo report of mine appeared in an important magazine.

“As always, I also made some prints for Bob, including his mother’s. Bill would deliver them to him.

“About a year later, I’m asleep at home — it’s 3 a.m. — when the phone rings. It’s Barry Imhoff, Bill Graham’s partner. ‘Hey Ken! How’re you doing?’

“I shout: ‘It’s damn 3 o’clock in the morning. I’m asleep! You there in California don’t take into account the time difference.’

“He says, ‘No, I’m in New York. I wanted to know if you have anything to do in the next few months.’

“I say, ‘No idea. I work for a few magazines. What’s up?’

“‘Yeah look, Bill and I are setting up a little tour and we were wondering if you were interested.’ I asked, “Can you tell me a little bit more?” He gives me Louie Kemp, a childhood friend of Dylan’s, who tells me that it’s a Bob Dylan tour and that they want to see me and if I want to cover the whole tour. I ask to speak to Barry again and cackle him out: ‘Man it’s 3 a.m. I don’t feel like having my leg pulled now’.”

“For a moment it is quiet on the line and then I hear a voice that I immediately recognize: Bob Dylan. ‘Ken, sorry we woke you up so early. We were rehearsing all day and I had no idea what time it was. I got your pictures and wanted to thank you for that, especially my mother’s. Because you didn’t use it, I know I can trust you. We want to see you. Bring your portfolio’.

“The next day I went to S.I.R. [Studio Instrument Rentals’ in Manhattan] where they were rehearsing. I saw Bob and Louie and Barry. After half an hour Bob said he would like me to do the tour. ‘It’s very unusual, because I’ve never done anything like this before. We will be away from home for about three months. Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, David Mansfield, T-Bone Burnett and some other people we pick up along the way will come along. We’re making a movie, which I’m directing, and I want you there to photograph everything, 24/7 – no restrictions. And no one else is allowed to take pictures.’

“During that tour I took 13,750 photos (4). Every night, after the performance or the party, Bob and I would sit together and look at the prints and he would say yes or no. He either approved of them or disapproved of them. After a few gigs, the phone calls came: People, Time, Rolling Stone… I told Bob and he said he expected something like that. ‘Just choose what you give to whom. Let me see them and make sure everyone has something exclusive.’ That was my big break at the magazines, because it was an exclusivity of Bob Dylan and it opened a lot of doors for me.”

“During that tour I took 13,750 photos (4). Every night, after the performance or the party, Bob and I would sit together and look at the prints and he would say yes or no. He either approved of them or disapproved of them. After a few gigs, the phone calls came: People, Time, Rolling Stone… I told Bob and he said he expected something like that. ‘Just choose what you give to whom. Let me see them and make sure everyone has something exclusive.’ That was my big break at the magazines, because it was an exclusivity of Bob Dylan and it opened a lot of doors for me.”

It can’t be a coincidence that out of those 13,750 photographs Bob Dylan chose one that is so similar to that of John Phillips, taken there on the first day of the Rolling Thunder Revue, in a park in Plymouth.

Why this picture? As is so often the case with Bob Dylan, he himself does not give any explanation.

The back sleeve

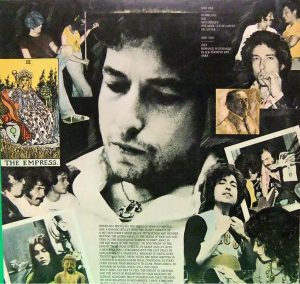

The back shows a collage by Carl Barile, head art director at the glossy magazine Avenue. Some of the black and white photos are hand tinted.

The back shows a collage by Carl Barile, head art director at the glossy magazine Avenue. Some of the black and white photos are hand tinted.

Ruth Bernal is credited on the inner sleeve for the “collage photos”, but Rob Stoner assured me, in a mail dated January 6, 2020: “Pics by Stephanie Chernikowsky”. Perhaps Ruth Barile only made the central portrait of Bob, which is also used for the inner sleeve.

The singer looks down thoughtfully on that central photo. Around his neck a necklace with an Egyptian-inspired jewel – a design by Edward Merrifield (whose wife was friends with Sara Dylan). Around it we see, starting at the top left and then turning like the hands of a clock: drummer Howard Wyett with violinist Scarlet Riviera. Then producer Don DeVito talking to his brother.

Below is a smaller portrait of Dylan, smoking and partially hidden under a drawing portraiting the writer Joseph Conrad. His 1915 novella Victory provided inspiration for the song ‘Black Diamond Bay’.’

Next we see Bob talking to Jacques Levy and at the bottom right Dylan in a baseball shirt, together with Sara.

Centre below is a text by Dylan, in which he talks about the landing at Plymouth Rock. Emmylou Harris is joined by a Buddha statue.

Above that: a photo with three people. It’s not clear who’s on the left, but according to Rob Stoner: “I’m on the far right of a trio with Dylan and Don DeVito. We are listening to a take at the mixing console. The song is ‘Abandoned Love;’ eventually released on Biograph. I’m the unidentified harmony singer on that track.”

Finally, the tarot card The Empress. A card that, according to the book by travelling journalist /writer Larry Sloman (5), always was prominently displayed in Sara’s hotel room.

Inner sleeve

For the vinyl release, the record itself was in a black protective cover. On one side, the large black and white portrait of Dylan is printed sheet filling. On the other side is a text by Allen Ginsberg, surrounded by the other photos of the back cover, with the Tarot card placed in the center. This time the photos are not colored.

Striking is the caption to the title Desire: ‘Songs of Redemption’.

Notes

- Although John Phillips’ debut album (January 1970) is untitled, the record is often referred to as ‘The Wolfking of L.A.’, after a poem printed on the back of the cover.

- Sam Shepard’s diary is later published as Rolling Thunder Logbook (The Viking Press, 1977/Penquin Books, 1978).

- Ken Regan – All Access: The Rock ‘n’ Roll Photography of Ken Regan (Insight Editions, 2011)

- Here’s a link to some of Regan’s photos about the tour.

- Larry Sloman – On the Road with Bob Dylan (Crown Publishing, 1978/Three Rivers Press, 2002)

Previous articles from this series

- Another side of Bob Dylan

- Biograph – see Empire Burlesque

- Blonde On Blonde: The Artwork

- Blood on the Tracks

- Bob Dylan

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- Bringing it All Back Home

- Desire

- Down in the Groove

- Dylan

- Empire Burlesque and Biograph artwork

- Good as I’ve been to you

- Greatest Hits Volume II

- Infidels: what’s in a name?

- John Wesley Harding: the art work

- Knocked Out Loaded

- Nashville Skyline

- New Morning

- Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid

- Self-Portrait

- Slow Train Coming

- Street Legal and the secret cover location

- The Basement Tapes

- The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan – the untold story of the artwork of the album

- The Times they are a changin’ album artwork

- Time out of Mind

- Travelling Wilburys Vol 1 (guest visitor, Michael Palin)

- Triplicate

- World Gone Wrong

Very interesting ..,,

Poet William Carlos Williams, mentioned in the album’s liner notes, focuses on emotional impact of “the image” …

Poet Ezra Pound deserted America, wandered off into an esoteric land unknown to the common man …

But Williams did not ….

The humanitarian doctor/poet never abandoned the ‘desire’ for progress, of the building of a biblical Promised Land in America, which he expresses in simple diction …

TS Eliot’s barren ‘wasteland” be damned.