Part 1: Ramona are you betta, are you well?

Part II: Whatever will be

by Jochen Markhorst

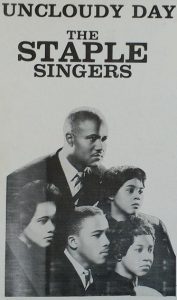

But biographical lines can be drawn to more ladies. Mavis Staples, for instance, would be another educated guess. As a young lad Dylan had already fallen in love with her voice (she was the youngest of the gospel group The Staples Singers), the impact of “Uncloudy Day” he still feels almost 60 years later, he says in the AARP interview in March 2015:

But biographical lines can be drawn to more ladies. Mavis Staples, for instance, would be another educated guess. As a young lad Dylan had already fallen in love with her voice (she was the youngest of the gospel group The Staples Singers), the impact of “Uncloudy Day” he still feels almost 60 years later, he says in the AARP interview in March 2015:

“One night I was lying in bed and listening to the radio. I think it was a station out of Shreveport, Louisiana. I wasn’t sure where Louisiana was either. I remember listening to the Staple Singers’ “Uncloudy Day”. And it was the most mysterious thing I’d ever heard. It was like the fog rolling in. I heard it again, maybe the next night, and its mystery had even deepened. What was that? How do you make that? It just went through me like my body was invisible. What is that? A tremolo guitar? What’s a tremolo guitar? I had no idea, I’d never seen one. And what kind of clapping is that? And that singer is pulling things out of my soul that I never knew were there. After hearing “Uncloudy Day” for the second time, I don’t think I could even sleep that night.”

… and he also remembers the youthful conviction one day you’ll be standing there with your arm around that girl as he stares at her picture on the cover of the eponymous LP from 1959. And sure enough, one day he is standing with his arm around Mavis. Hardly three years later. In the scene he meets The Staples Singers, the admiration is mutual. Besides “Blowin’ In The Wind” the sisters and “Pops” sing five more Dylan songs, and a Dylan in love even asks for the hand of Mavis. Years later, Mavis does have some regrets that she refused at the time, but they remain friends. And according to Mavis they still had an amorous period, in those years. But getting married, no. Also because, as Mavis says, she thought that Rev. Martin Luther King wouldn’t like it if she married a white man.

A link to Ramona is in line with this: the pitying making you feel that you must be exactly like them. And with some pushing and pulling, there could more biographical traces to Mavis be found, but it really is not that important – neither is all too convincing. Dylan the Poet probably composes poems like most poets do; bits and pieces, an impression here and an association there, and from the mosaic thereof he constructs a coherent, poetic image of a fading relationship.

Lyrically, it is quite obvious that “To Ramona” is not so much a work of reason as of rhyme. The sought-after inner rhymes (breathlike – deathlike, a dream babe – a scheme babe, hype you – type you), the successful alliterations (magnetic – movements, from – fixtures – forces – friend), the flowing assonances (pangs of your sadness – pass at your senses): all stylistic figures from which above all love for playing with language speaks.

The music is enchanting. Completely unoriginal, of course, but who cares. A waltz, the melody follows traditional Mexican folk clichés and resembles a hundred other songs. “The Last Letter” by Rex Griffin, for example, Leadbelly’s “Goodnight Irene”, and with some tolerance you can even hear “Que Sera, Sera” in it (unless you consider the breath-taking version of the phenomenon Marcus Miller the standard, that is).

The accompaniment is as sober as all the songs on the record, the vocals are remarkably enough close to sneering, although the lyrics are content-wise partly quite tender. Dylan does not let go of the song either. To this day he continues to play it with some regularity, sometimes excessively arranged (and very successful; during the 1978 tour, for example), more often bare and acoustic, and always the master remains faithful to the waltz rhythm.

This also applies to most covers. There are plenty of them; “To Ramona” has been popular with colleagues since its release. And the song, like “Not Dark Yet” for example, almost always retains its power – you can hardly miss the mark, apparently. The Flying Burrito Brothers deliver a beautiful version in 1971, David Gray still regularly performs an intense “To Ramona”, Lee Hazlewood, Humble Pie and even the pounding These United States: all beautiful. Above all towers the superior, affectionate version that another old master recorded half a century ago: the one by Alan Price, that is.

Rivalling Price is only a brilliantly orchestrated interpretation by the young Irish Sinéad Lohan from 1996. The very talented, dreadlocked singer/songwriter from Cork is a bright comet to the firmament, around the turn of the century, and disappears just as suddenly. Reportedly dedicating herself to motherhood full-time, back home in Cork.

Pity, because her two albums, Who Do You Think I Am from 1995 and No Mermaid from 1998, suggest that she has many more wonderful songs up her sleeve. Which is recognised. By Joan Baez, for instance, who records two of her songs (both title songs, for Gone From Danger, 1997) and the Californian newgrass trio Nickel Creek, who recorded Lohan’s “Out Of The Woods” for their platinum debut album.

About that particular song, Sinéad has mixed Dylan feelings, by the way. She tells how relaxed it was, back then, recording her second album in New Orleans. Everything was so laid-back, she says;

“No pressure at all. And I really was going to call this Time Out of Mind because that is a line in one of the songs, “Out of The Woods”. But then I opened a paper and said ‘My God! Bob Dylan has stolen my line. The cheeky git!’ So I had to change it!”

At first it sounds like the unworldly gibberish of an ingenue with a somewhat inflated self-image, and at second glance like a clumsy joke, but then one notices the name of her producer: Malcolm Burns. Burns is Dylan’s technician on both Oh Mercy and Time Out Of Mind – and for the latter album he works with Daniel Lanois and Dylan right after the recording of No Mermaid, also in New Orleans. Suddenly it’s not so far-fetched anymore, the idea that Dylan might have heard what Malcolm Burns was working on, two weeks ago, and that Dylan heard Sinéad singing:

I rollercoaster for you Time out mind Must be heavenly It's all enchanted and wild It's just like my heart said It was going to be

In the interview with Joe Jackson for Hot Press, March 2001, Lohan does not laugh it off completely, in any case. And it has spoiled the fun of Dylan’s new album as well:

“I think people just got excited because it was Bob Dylan, making that album. So after all the hype, I was disappointed. I wanted songs that get to me. And that long one at the end (‘Highlands’) just made me go, ‘Bob, what are you doing?’ It just goes on and on! So, a lot of it is just too much. I prefer to listen to his older albums, like Another Side of Bob Dylan, which is where I got ‘To Ramona’, that was a single here for me a while ago.”

Which gives her much better Dylan feelings. Her American manager Mark Spector is an acquaintance of Dylan’s manager Jeff Rosen, who says that he played Dylan Sinéad’s cover:

“Dylan apparently heard it and said he wanted his ‘sentiments expressed to the singer’ that he ‘liked’ the version I did. That’s a nice compliment, I guess. If it’s true.”

Well, it just might be true. Sinéad’s layered, undercooled, veiled and hazy rendition is one of the most delightful covers of “To Ramona”, and that is saying something, in a playing field with The Flying Burrito Brothers, Joan Baez, Lee Hazlewood and Freddy Fender… to name but a few.

”I’ll come and be cryin’ to you”… bizarrely, it is never sung more poignantly than by some 25-year-old lass with dreadlocks from Cork, Ireland.

————

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits (German)

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

Untold Dylan

We now have over 2000 articles on this site. You can find indexes to series linked under the image of Dylan at the top of the page and some relating to recent series on the home page.

Although no one gets paid for writing, publishing or editing Untold Dylan, it does cost us money to keep the site afloat, safe from hackers, n’er-do-wells etc. We never ask for donations, and we try to survive on the income from our advertisers, so if you enjoy Untold Dylan, and you’ve got an ad blocker, could I beg you to turn it off while here. I’m not asking you to click on ads for the sake of it, but at least allow us to add one more to the number of people who see the full page including the adverts. Thanks.

As for the writing, Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Although no one gets paid, if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8500 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

“In general, the inhabitants of Göttingen are divided into students, professors, philistines and cattle, which classes are nothing less than strictly separated. The cattle class is the most important. The city itself is lovely and most pleasing to look upon with your back turned to it.” (The Harz Journey, 1826)

“In general, the inhabitants of Göttingen are divided into students, professors, philistines and cattle, which classes are nothing less than strictly separated. The cattle class is the most important. The city itself is lovely and most pleasing to look upon with your back turned to it.” (The Harz Journey, 1826)

Steve Crawford, also writing to the site, after my original piece was published had this additional interesting observation…

“The piece works at 3 levels. First, it tells a story, as all good songs do, at a very personal level. The story is about a man amidst his reflections of what he has lost as he revisits his past and re-experiences finding and losing love.

“Second, it is an invitation to explore the reflections and the emotions as we travel down his path of awareness, by tenses (today, tonight, tomorrow), and by the loss of senses, (I can’t see, I can’t speak, I can’t hear). ”

The third is to share both the joy and the sorrow of realizing that life’s beauty is temporal, leaving only memories of what was, – there’s beauty in the silver singing river, there’s beauty in the sun that lights the skies, but none of these, or nothing else can match the beauty, that I remember in my true loves eyes. Perfect rhyme, perfect meter, perfect images reflect a true master at his craft, and weaving his beautiful web. I learned this song back in 1967, have performed it 2468 times, and know what it is about.”

Robert Van Tol took us down a different route with the comment “Sacrilege Alert…I have always preferred Rod Stewart’s cover to Dylan’s original & love the “Run Down Rehearsals” version.”

OK, so Rod Stewart it is…

And we have the Rundown Rehearsal version…

This triggered more responses – and again can I say just how grateful I am to everyone who writes in to Untold. There’s no way I can reply to all the issues raised, and keep my regular life running but I do note what is said.

Ronald Perz wrote…

One of my all time favourites since 1971. I like Sandy Dennys Version too. Elvis. Ian and Sylvia. Bob and Jerry

Thomas Parr responded to Steve Crawford’s commentary, finding them very thought provoking and adding, “Upon hearing this song for the first time I must have played it 50 times that very day and many more times in the days to follow.

“It is the story of a mans existence being experienced as non-existence.I cant see, I cant speak, I cant hear. the strong symbolism of the bed too speaks to a man who is utterly lost: ones bed is home, it is safety and it is refuge. To be deprived of it shows how abjectly alone the singer is. This is how I’ve always interpreted the song.

Steve Crawford’s comments though give reason to look deeper.

“To me it is the quintessential love song, categorically different from nearly everything of the last 50 years.

And thanks to Richard Slessor for reminding us all that Judy Collins has of course visited the song, and I really should have included this in my original review. Thank goodness for commentators putting me right.

But of course there is only one place we can finish. Bob said one time this was the recording he valued above all others in terms of covers of his songs…

If you’d like to suggest a song of Dylan’s to include in this series – or indeed if you would like to write the article yourself, rather than have me endlessly pontificating, please do email your article as a word document to Tony@schools.co.uk

Just remember the theme here is that the song is a work of magic which will have been missed by many people.

Untold Dylan

We are approach 2000 articles on this site. You can find indexes to series linked under the image of Dylan at the top of the page and some relating to recent series on the home page.

Although no one gets paid for writing, publishing or editing Untold Dylan, it does cost us money to keep the site afloat, safe from hackers, n’er-do-wells etc. We never ask for donations, and we try to survive on the income from our advertisers, so if you enjoy Untold Dylan, and you’ve got an ad blocker, could I beg you to turn it off while here. I’m not asking you to click on ads for the sake of it, but at least allow us to add one more to the number of people who see the full page including the adverts. Thanks.

As for the writing, Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Although no one gets paid, if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8500 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down