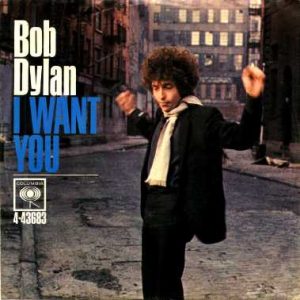

Beautiful Obscurity

This series, compiled by Tony Attwood, takes a new look at the best ever – or at least some of the more unusual – cover versions of Bob Dylan’s music. Previously we have had…

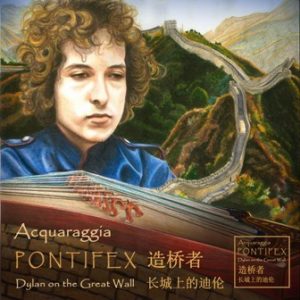

- Beautiful Obscurity: Acquaraggia play Dylan: a new experience

- What makes a beautiful obscurity

- “The 100 Greatest Cover Versions of Bob Dylan songs ever”

- Beautiful obscurity: revisiting the alternative versions of Sweet Marie

- Beautiful obscurity: unexpected reworkings of “All along the watchtower”

- Beautiful Obscurity: such different renditions of Spanish Leather

Today, it is Every Grain of Sand.

We all know the song, and most commentators have had their bash at describing it, and nigh on everyone calls it a masterpiece. I think Jochen on this site described it perfectly, being “imbued with the Lutheran vision that suffering in this earthly valley of tears is our destiny, until death comes to redeem us.”

Nana Mouskouri has claimed that after a concert of hers she and Bob went out for a meal and “he wrote Every Grain Of Sand‘ for me” and thus Ms Mouskouri puts it on her next album. Jochen’s view is that “The versions by Emmylou Harris, especially the studio version of Wrecking Ball (1995, produced by Dylan expert Daniel Lanois), can hardly be improved and overshadow all the other covers.” I’m hoping I’ve picked up the right version here – Jochen do tell me if not.

The issue for everyone singing the song is whether to go with the snare drum double beat or not. Ms Harris does, and she gets away with it completely because the accompaniment is so perfectly balanced, that the snare is never overpowering, and it changes as the melody changes for two lines. Plus she puts in her harmonies there, and only there, to add to perfection (if that is possibly, which technically it isn’t).

Jochen taunts us in his piece with a reference to the Blind Boys of Alabama version. They feel the need for some sort of percussion, but not that normally used – but I don’t really understand the point here. What is the drum part saying to us in this otherwise beautiful version? It is, for me, as the lyrics have it at one moment, an indulgence – to such a degree I can hardly listen.

Luka Bloom vary the melodic line and add a new accompaniment but for me this feels as if everyone (musicians and vocalist) is simultaneously holding back but still wanting to be noticed. I think the problem is exacerbated by a chunky rhythm with a clink counter melody that seems to be there because someone thought let’s have a secondary instrumental melody at the same time but no one asked why.

Above all I think this is one of those arrangements where everyone had an idea and they just let them all happen, without having an arranger in chief or producer or director there who is going to say, “Hang on guys, there is just too much here”. Or maybe they were told but no one wanted to lose their little bit.

It is worth heading back from that experience to Bob, to see where he went. He uses harmonies but they are restrained and the instrumentation knows it is background, and that is where it stays. Yes there is a lot here, but every player knows his place just as grain of sand knows its place. Except… my only concern is the harmonica… I don’t think we needed anything more. There were enough instruments out there – but I guess no one could tell Bob.

There is a real temptation with this song to perform it as four solid beats in each bar, but that is not what the song really is, as we can tell with this edition from Madison Cunningham. She has a gorgeous voice and can deliver a simple, straight performance without variation, but when stripped down to the minimum, there is a feeling that we need more. It is just that double beat of a drum is not the “more” that I need.

Luka Bloom takes the accompaniment to a mid-point and in the opening seconds I feel this really is just what I need from this song, but then the change of the melody turns me away, because a fundamental part of the glory of the song is the melody. There are many Dylan songs that can be given an extra life by changing the melody (Dylan has done it himself many times of course) but for me this is not one of them. Or if it does need a new melodic interpretation, then it needs something on a par with the glorious original, and we don’t get that.

So let us pause for a moment and remind ourselves where Bob took this piece when he was playing it without the pulsing drum double beat.

It is a relief to get back to the original melody – what a gorgeous creation it is. But is that a glockenspeil I hear behind; oh no! Actually no I don’t think it is, I think it is an electronic keyboard with the “glock” tone clicked down. So once again I find myself hearing something not needed. Imagine this delicious rendition without the tinny twinkly pinging of metal on metal. Fortunately the instrument is not always there so it can be done.

Twinkly twinkly goes the introduction of the Peter Viskinde Band- the influence of the glockenspiel is still here. If you can listen to the version below and get to the “glory of the moment” when the glock sound has gone, I think you may see what I mean. Sadly, the wretched twinkly sound comes back, and the organist even feels like adding a twinkle too. I feel I just want simplicity.

And so thank you thank you Amanda Ghost (or possibly Gohst – as I have found it written on one site). Yes you can have percussion, yes you can have a repeating bass (although if I’d do anything here I’d take it out), but I do like this. And this version makes me think, maybe the song is so beautiful no human can actually fully realise its beauty. In my head I know where it could be, but I certainly couldn’t arrange that in reality, even given the greatest performers on the planet.

Of course there are more and more recordings, and if you have not had enough, you might want to try these…

Each one goes somewhere new…

And yes, even Bob has a go…

While occasionally some to a planet I can’t actually recognise or relate to

And – blimey – you are still here are you? Wow, that is resilience. So yes, of course you need a reward. Now of course I don’t know if you share any of my feelings for this wonderful musical creation, and quite possibly you have consigned my views to a dustbin marked irrelevance.

But this one is the closest to what is in my mind.

I got there in the end.

What else?

You can read about the writers who kindly contribute to Untold Dylan in our About the Authors page. And you can keep an eye on our current series by checking the listings on the home page

You’ll also find, at the top of this page, and index to some of our series established over the years. Series we are currently running include

- The art work of Bob Dylan’s albums

- The Never Ending Tour year by year with recordings

- Bob Dylan and Stephen Crane

- Beautiful Obscurity – the unexpected covers

- All Directions at Once

You’ll find links to all of them on the home page of this site

If you have an article or an idea for an article which could be published on Untold Dylan, please do write to Tony@schools.co.uk with the details – or indeed the article itself.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with getting on for 10,000 members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

The Beautiful Obscuriti series aims to find little known or even unknown reworkings of Bob Dylan’s music, and with this in mind I have been sent a copy of the album Pontifex by Acquaraggia from which I’m going to offer a few recordings below.

The Beautiful Obscuriti series aims to find little known or even unknown reworkings of Bob Dylan’s music, and with this in mind I have been sent a copy of the album Pontifex by Acquaraggia from which I’m going to offer a few recordings below.