All Directions at once: how Dylan chooses what to write

- 1: A song is like a painting, you can’t see it all if you’re standing too close

- 2: All directions at once: how Dylan’s lyrics empower those who wish to be empowered

- 3: All Directions at once: The prelude to the explosion (1959-1961)

- 4: All directions at once: The explosion (1962).

- 5: All directions at once: Making a name, getting known, arguing about copyright

- 6: All directions at once: learning the folk, moving on

By Tony Attwood

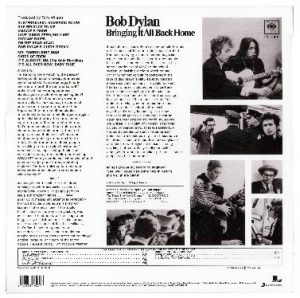

In my last article in this series I argued that Dylan had become a man who could operate in a whole wide range of song styles, while at the same time he had become the ultimate storyteller, able to write protest songs, love songs, gambling songs, the blues etc etc etc.

Also we looked at how Bob could not only take up the themes he had previously considered (songs of leaving, lost love, protest etc) but also bring into focus new themes such as individualism, and the thought that what defines us as individuals is the way in which we choose to see the world – not the way the world is. A sophisticated concept not generally explored in popular music – or indeed in folk music.

The old year had ended on such a high with the creation of songs we now see as classics – songs such as When the ship comes in, The Times they are a-Changing, The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, One too many mornings and Restless Farewell. I imagine there must have been some debate within his record company,at this point, as to whether Bob could possibly keep up this pace and this quality of writing. I wouldn’t be surprised if someone had said, “Even if the next batch are only half as good, we’ve still got more than enough for the next album.” Looking back, the quality and quantity of Dylan’s creativity at this time was astonishing.

But the issue of the future was serious: after songs like that, would Bob Dylan now go into eternal decline as so many artists have done after the first flourish artistic brilliance? And anyway, what on earth could Dylan do to top all that he had done? He had composed 20 highly memorable songs in each of the last two years – more than most songwriters can do in a lifetime. Could he really keep up the quality of his writing, the variety of styles and the sheer volume of excellent new songs for another year?

Of course as we know now, the answer turned out to be, most assuredly, “yes”. Inevitably we find some songs that don’t get an automatic mention in any list of Bob’s greatest songs, as with his opening piece in the new year Guess I’m doing fine – an ironic work in which Bob actually says he is hurting. But after that warm up, songs of the highest quality emerged once more from his typewriter, one after the next after the next. And again that by-now famous ability to keep changing his subject matter was on display.

In my original article on this site exploring this year, in which I pulled together the list of songs written in the chronological order or their composition, I ascribed the shortest possible description of each song’s lyrics. What I didn’t particularly note however was the remarkable fact (or at least it would have been remarkable in any other songwriter) that the first eight songs of the year were each on very different themes…

- Guess I’m doing fine (I’m hurting)

- Chimes of Freedom (Protest)

- Mr Tambourine Man (Surrealism; the way we see the world)

- I don’t believe you (She acts like we never have met) (Lost love)

- Spanish Harlem Incident (Love)

- Motorpsycho Nightmare (Humour)

- It ain’t me babe (Song of Farewell)

- Denise Denise (Taking a break, having a laugh)

If we didn’t know about thing about Bob’s work and were to listen to “Guess I’m doing fine,” the first song of the year, I think any record company A&R man of the day might be tempted to say, well, ok, keep trying Bob; it’s interesting but see what else you can come up with – and then give us another call.

This is not to say that “Doing fine” is a bad piece of music, but rather when one compares it with all that has gone before, it really isn’t anything special. In fact, if you leave that recording above running it moves onto the album release of “Restless Farewell” written just a short while before. The contrast is extraordinary.

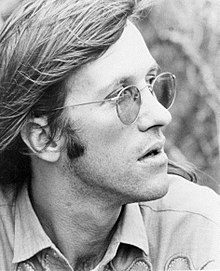

Thus a person, unfamiliar with Dylan’s work but hearing his reputation, would I suspect have been disappointed. But that disappointment would have been short lived because the very next piece Bob wrote was one of his all-time classic works: Chimes of Freedom. I particularly like this video below because if you watch the mess of the start, it is hard to imagine that this guy is going to deliver anything, yet alone this piece of artistic mastery…

The core message of the song is encapsulated in that opening verse – there is hope for everyone who is not part of the powerful or the elite. We are all going to be liberated from the shackles of this world. Just hold on in there. It’s a matter of how you see the world, not the way the world is…

And just in case we haven’t got who it was he was thinking about…

Tolling for the rebel, tolling for the rake Tolling for the luckless, the abandoned an’ forsaked Tolling for the outcast, burnin’ constantly at stake An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing

It is a most extraordinary song of hope, packed with the most brilliant images. A song that takes the inevitably better future message of “Times they are a changin” and which then tells us what it will feel like.

Take this verse which appears part way through…

Through the wild cathedral evening the rain unraveled tales For the disrobed faceless forms of no position Tolling for the tongues with no place to bring their thoughts All down in taken-for-granted situations Tolling for the deaf an’ blind, tolling for the mute Tolling for the mistreated, mateless mother, the mistitled prostitute For the misdemeanour outlaw, chased an’ cheated by pursuit An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing

Maybe I missed it, but had anyone else thought of writing a folk or pop song like this before? Had anyone else ever thought of writing a song in the popular style which ended with as much hope and positively as the lines that end this song without actually being overtly religious.

And indeed that is another point about this song: it offers the joyful future of Christian revivalist singing, without any of the religion.

Starry-eyed an’ laughing as I recall when we were caught Trapped by no track of hours for they hanged suspended As we listened one last time an’ we watched with one last look Spellbound an’ swallowed ’til the tolling ended Tolling for the aching ones whose wounds cannot be nursed For the countless confused, accused, misused, strung-out ones an’ worse An’ for every hung-up person in the whole wide universe An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing

Writers have commented on this song in many different ways; Rimbaud has been quoted as a source, others see the death of Kennedy as a theme. Paul Williams called it “Dylan’s Sermon on the Mount.” Others get tangled up over when and where the piece was written, trying to find immediate influences and antecedents. And I agree these are interesting points. I also went looking for antecedents, but I would stress, not because I thought they were desperately important, but because I like to try to keep the vast number of songs in my head in some sort of order.

So for anyone who wants to go down that route then musically I’ve little doubt that the origin is Chimes of Trinity written in 1895 (if you play the recording do let it run – you’ll hear what I mean in the second half of the verse – from about 1 minutes 5 seconds onwards).

But as ever, the origin of the language and indeed the music, is an academic debate, interesting, and one which I’ll drop into my PhD if I ever finish it, but which can also be used by academics and would-be academics to hide their lack of understanding as to exactly what is going on in the work of art.

Does it matter that Bob lifted the music in part from “Chimes of Trinity”? No, but it is interesting because it shows us he must have heard “Chimes of Trinity” somewhere – which in turn emphasises the phenomenal range of music that Bob had not only heard but also remembered, but this time.

In my view, and as I have mentioned before, breaking down a work of art into its constituent elements often tells us less than nothing about the work of art. It’s a bit like studying the brick work at St Paul’s Cathedral and expecting to learn something profound about Sir Christopher Wren. The artist, be she or he a musician, painter, poet, architect, dancer… is creating a work. A fulsome piece which is offered to anyone willing to look and/or listen and/or be inspired as a means of passing the time of day or perhaps gaining an insight into an aspect of the world today or the world beyond. That’s what art is.

If we reduce this song to a “meaning” and suggest perhaps that (as Wikipedia has it) it is an “unforgiving storm giving way at the end of the song to a partial lifting of the mist,” then every single element in the song is lost and its glorious language is reduce to doggerel.

Ian Bell, an eminent and highly acclaimed writer, says that the this song is about the fact that liberty exists in many forms, and yet the song is “too over-wrought and self-conscious to be a total success,” I have to disagree. To return to a point I made much earlier in this series, I am not at all sure that one can say what this song is about, any more than one can say what the Millennium Bridge in London is about.

But I have walked that footbridge between St Pauls and the Tate Modern art gallery countless times, and each time I am completely overwhelmed by my approach either to the cathedral or what was once upon a time a power station. I can’t describe that walk in any way that might convince another person to do the walk, but it is, for me overpowering.

In short we do not have to be able to explain art to understand its power. I can of course give you the chord sequence of the song, report on its origins or look in depth at the words, but none of that helps me express to you what this song is. Your best bet, in my view, is to listen to the recording above.

Also, I don’t recommend you spend long on this cover version but to my mind the arranger and performers have not got the slightest idea of what is going on in the piece.

Endless debates about where the lyrics “come from” and what they mean are futile, to my mind. The composition is a work of art which either illuminates your life or it does not. To me, it most certainly does illuminate. The sheer beauty, power and hope expressed therein. Breaking it down into points in a critical debate immediately removes a key part of the essence of the the song.

For me, it was the decision of the self-appointed critics of Dylan’s work around this time to express the meaning in each and every song that led to the collapse into pointlessness of critical reviews of Dylan’s work. If Dylan wants to make the meaning clear, he is perfectly able to do so – just consider “Masters of War”. If he wants to give us a set of shimmering images of hope, he can do that. He can do it because he has this staggering ability with words, and to start analysing the antecedents or meanings in this song shows, I feel, a complete lack of understanding of what not only this art but all art, is about.

Yes such analysis can be interesting as an academic study of antecedents or meanings, but this activity should not be confused with appreciating the music for what it is.

But this is not to say one should not look at individual lines. The line, “for every hung up person the whole wide universe,” for example, resonates especially as the next three songs Dylan wrote show a certain amount of being hung up – although there again, maybe that was just a coincidence.

The series continues shortly. If you have been, thank you for reading.

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down