- Dreamin’ Of You (1997) part 1: Dreamin’ of Henry

- Dreamin’ Of You (1997) part 2: The Lay of the Last Minstrel

III I don’t reckon I got no reason to kill nobody

Maybe they’ll get me, maybe they won’t / But whatever it won’t be tonight I wish your hand was in mine right now / We could go where the moon is white For years they had me locked in a cage Then they threw me onto the stage Some things just last longer than you thought they would And they never, ever explain I’ve been dreamin’ of you, that’s all I do And it’s driving me insane

Allen Holdsworth was an inimitable British guitar magician for whom even men like Frank Zappa, Eddie Van Halen and Joe Satriani took their hats off. Contributions to projects by names like U.K., Stanley Clarke and Level 42 are, without exception, Olympic, but Holdsworth (1946-2017) was never really a team player – perhaps a little too self-willed and uncompromising. His true passion was his solo projects, filled with mainly instrumental exercises at the outer limits of guitar virtuosity and eccentric soundscapes. Perhaps not too accessible, but always fascinating. Like his eleventh and last studio album Flat Tire: Music for a Non-Existent Movie (2001). It is – as the title already reveals – a very atmospheric album with, as one of the highlights, the disturbing “Snow Moon” – just as disturbing and even more ominous than Dylan’s We could go where the moon is white, by the way.

Allen Holdsworth was an inimitable British guitar magician for whom even men like Frank Zappa, Eddie Van Halen and Joe Satriani took their hats off. Contributions to projects by names like U.K., Stanley Clarke and Level 42 are, without exception, Olympic, but Holdsworth (1946-2017) was never really a team player – perhaps a little too self-willed and uncompromising. His true passion was his solo projects, filled with mainly instrumental exercises at the outer limits of guitar virtuosity and eccentric soundscapes. Perhaps not too accessible, but always fascinating. Like his eleventh and last studio album Flat Tire: Music for a Non-Existent Movie (2001). It is – as the title already reveals – a very atmospheric album with, as one of the highlights, the disturbing “Snow Moon” – just as disturbing and even more ominous than Dylan’s We could go where the moon is white, by the way.

Holdsworth is not the first and not the last to try to capture a strong visual idea in music, or to think, after the creation of the music: my, this sounds like a movie soundtrack. Elton John calls his short instrumental interlude on his unjustly somewhat forgotten Blue Moves (1976) “Theme From A Non-Existent TV Series”. Radiohead’s pièce de résistance OK Computer contains the heartbreaking “Exit Music (For A Film)”, which, incidentally, was indeed originally intended for the closing credits of the film Romeo + Juliet (1996). Complete albums by Eno (Music for Films from 1978, Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks, and more), side 2 of Bowie’s Low… non-existent films and fantasised scenes prove to be a fertile source of inspiration for many artists.

The suspicion that Dylan wanted to write a veiled murder ballad à la “Soon After Midnight” (Tempest, 2012) with “Dreamin’ Of You”, or at least leave the suggestion open, as in “Cold Irons Bound” and “Dirt Road Blues”, gains more weight in this third decastich. “Maybe they’ll get me”, “locked in a cage’, “thrown onto the stage”… this narrator chooses images and words that, at the very least, insinuate a conflict with law enforcers.

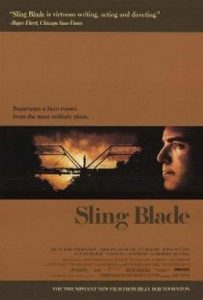

Fitting also with the chosen music, its arrangement and colour. The outtake we finally get in 2008, as a free download to promote the upcoming release of The Bootleg Series Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs is, if anything, very, very Lanoisesque. This sound and atmosphere is familiar to us from Lanois’ work for Robbie Robertson’s first solo album, for instance, for a great song like “Somewhere Down The Crazy River”, and equally from Lanois’ more recent solo effort, the beautiful soundtrack for the film Sling Blade (1996). In musical highlights of that soundtrack like “Blue Waltz”, “Asylum” and especially the brilliant “Jimmy Was”, the colour of “Dreamin’ Of You” is unmistakably already pre-cooked, probably also thanks to co-producer Mark Howard, who is the engineer for Time Out Of Mind a few months after recording Sling Blade. We hear the same space, the same reverb of Lanois’ guitar notes swirling around in “Shenandoah”, “Bettina” and “Secret Place”, his very characteristic carpet of guitars at all, all over the soundtrack, and on “Jimmy Was” the drum part is even almost identical to “Dreamin’ Of You”;

Besides the sound of the soundtrack, Dylan’s lyrics occasionally skim remarkably close along the film script – as this verse seems to express the introduction of Billy Bob Thornton’s Karl Childers. Twenty-five years ago, as a twelve-year-old, the feeble-minded Karl murdered his mother and her lover, and has been put away in a mental hospital ever since. And now he is being released: For years they had me locked in a cage / Then they threw me onto the stage. He is cured, or at least: no longer considered a danger to society. Which Karl can relate to: “I don’t reckon I got no reason to kill nobody.” Incidentally, according to Dylan researcher Scott Warmuth the direct inspiration comes again from Henry Rollins; “For years they had me locked in a cage” is the opening line of one of the poems in his See a Grown Man Cry: Collected Work, 1988-1991.

Likewise, the potentially romantic walk in the moonshine happens to be in keeping with a film scene;

LINDA

Karl, why don’t you and Melinda go take a walk. It’s nice out.

KARL

All right then.

He gets up and walks toward the front door. Melinda gets up and tries to catch up.

EXT. SIDEWALK – NIGHT

Karl and Melinda are walking in the moonlight. It seems a little hard for Melinda to keep up.

… but that scene is above all touchingly awkward and funny, and has no relation whatsoever to the subcutaneous threat in Dylan’s I wish your hand was in mine right now / We could go where the moon is white. The adjective “white” is particularly striking – in song and poetry, a colourless moon is actually always “pale”. “Copper Kettle”, “Sleepy Time Down South”, Hank Williams’ “When God Comes And Gathers His Jewels”, “East Of The Sun”, the American Songbook monument “The Nearness Of You”… all songs from Dylan’s jukebox with moonlight, and that light is always pale. “White” is a tad more ominous, maybe that’s why. And a bit more nineteenth-century, perhaps – both Melville and Poe sometimes colour their moon white too. Melville in Dylan’s beloved Moby Dick (“as the white moon shows her affrighted face from the steep gullies in the blackness overhead”) and Poe in his early work Tamarlane (1827);

What tho' the moon—the white moon Shed all the splendour of her noon, Her smile is chilly—and her beam, In that time of dreariness, will seem (So like you gather in your breath) A portrait taken after death.

… in both cases, evidently, to give a threatening, sinister touch to the narrative. And it is of course, for the third time already in this Dylan song, again a director’s instruction for the lighting technician.

The repetitiveness of the endlessly repeated five-tone lick over the same four chords from start to finish strengthens the suspicion: the film fan Dylan sees a film scene in his mind’s eye during the creation of the song – like one of those wordless interludes in which the camera follows the protagonist on his way to the next key scene. He walks along a dusty road at sunset, we get a backlit wide shot of a panoramic landscape and a lonely protagonist trudging along, a close-up of the man on a bridge staring at the water flowing underneath, usually interspersed with slow-motion flashbacks in sepia tones, of the man at the grave of a child, something like that. An interplay, in any case, where the director needs music, preferably with a repeating motif and minor chords.

It is beginning to look as if Henry Rollins has projected an unsettling character onto Dylan’s inner white screen – and that the musician Dylan hears the soundtrack to it.

To be continued. Next up Dreamin’ Of You part 4: If moonshine don’t kill me

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang